Reprinted with permission from ProPublica

In November 2017, with the administration of President Donald Trump rushing to get a massive tax overhaul through Congress, Sen. Ron Johnson (R-WI) stunned his colleagues by announcing he would vote "no."

Making the rounds on cable TV, the Wisconsin Republican became the first GOP senator to declare his opposition, spooking Senate leaders who were pushing to quickly pass the tax bill with their thin majority. "If they can pass it without me, let them," Johnson declared.

Johnson's demand was simple: In exchange for his vote, the bill must sweeten the tax break for a class of companies that are known as pass-throughs, since profits pass through to their owners. Johnson praised such companies as "engines of innovation." Behind the scenes, the senator pressed top Treasury Department officials on the issue, emails and the officials' calendars show.

Within two weeks, Johnson's ultimatum produced results. Trump personally called the senator to beg for his support, and the bill's authors fattened the tax cut for these businesses. Johnson flipped to a "yes" and claimed credit for the change. The bill passed.

The Trump administration championed the pass-through provision as tax relief for "small businesses."

Confidential tax records, however, reveal that Johnson's last-minute maneuver benefited two families more than almost any others in the country — both worth billions and both among the senator's biggest donors.

Dick and Liz Uihlein of packaging giant Uline, along with roofing magnate Diane Hendricks, together had contributed around $20 million to groups backing Johnson's 2016 reelection campaign.

The expanded tax break Johnson muscled through netted them $215 million in deductions in 2018 alone, drastically reducing the income they owed taxes on. At that rate, the cut could deliver more than half a billion in tax savings for Hendricks and the Uihleins over its eight-year life.

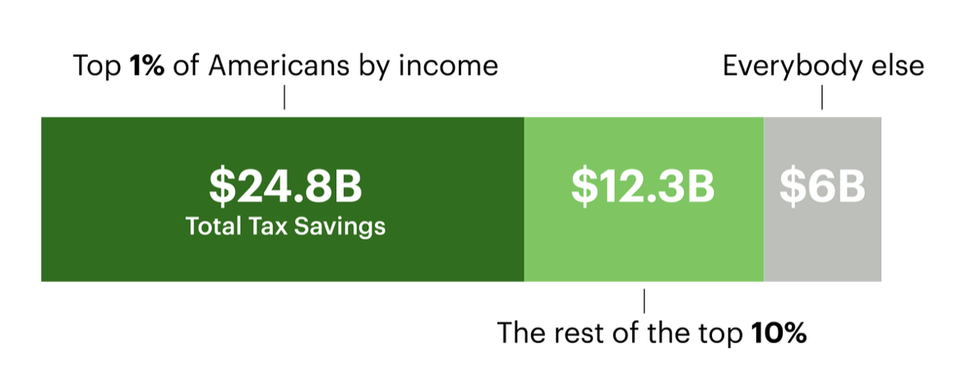

But the tax break did more than just give a lucrative, and legal, perk to Johnson's donors. In the first year after Trump signed the legislation, just 82 ultrawealthy households collectively walked away with more than $1 billion in total savings, an analysis of confidential tax records shows. Republican and Democratic tycoons alike saw their tax bills chopped by tens of millions, among them: media magnate and former Democratic presidential candidate Michael Bloomberg; the Bechtel family, owners of the engineering firm that bears their name; and the heirs of the late Houston pipeline billionaire Dan Duncan.

Usually the scale of the riches doled out by opaque tax legislation — and the beneficiaries — remain shielded from the public. But ProPublica has obtained a trove of IRS records covering thousands of the wealthiest Americans. The records have enabled reporters this year to explore the diverse menu of options the tax code affords the ultra-wealthy to avoid paying taxes.

The drafting of the Trump law offers a unique opportunity to examine how the billionaire class is able to shape the code to its advantage, building in new ways to sidestep taxes.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was the biggest rewrite of the code in decades and arguably the most consequential legislative achievement of the one-term president. Crafted largely in secret by a handful of Trump administration officials and members of Congress, the bill was rushed through the legislative process.

As draft language of the bill made its way through Congress, lawmakers friendly to billionaires and their lobbyists were able to nip and tuck and stretch the bill to accommodate a variety of special groups. The flurry of midnight deals and last-minute insertions of language resulted in a vast redistribution of wealth into the pockets of a select set of families, siphoning away billions in tax revenue from the nation's coffers. This story is based on lobbying and campaign finance disclosures, Treasury Department emails and calendars obtained through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit, and confidential tax records.

For those who benefited from the bill's modifications, the collective millions spent on campaign donations and lobbying were minuscule compared with locking in years of enormous tax savings.

A spokesperson for the Uihleins declined to comment. Representatives for Hendricks didn't respond to questions. In response to emailed questions, Johnson did not address whether he had discussed the expanded tax break with Hendricks or the Uihleins. Instead, he wrote in a statement that his advocacy was driven by his belief that the tax code "needs to be simplified and rationalized."

"My support for 'pass-through' entities — that represent over 90% of all businesses — was guided by the necessity to keep them competitive with C-corporations and had nothing to do with any donor or discussions with them," he wrote.

Trump Tax Overhaul Showered Millions on Handful of Americans

Source: ProPublica analysis of IRS data

By the summer of 2017, it was clear that Trump's first major legislative initiative, to "repeal and replace" Obamacare, had gone up in flames, taking a marquee campaign promise with it. Looking for a win, the administration turned to tax reform.

"Getting closer and closer on the Tax Cut Bill. Shaping up even better than projected," Trump tweeted. "House and Senate working very hard and smart. End result will be not only important, but SPECIAL!"

At the top of the Republican wishlist was a deep tax cut for corporations. There was little doubt that such a cut would make it into the final legislation. But because of the complexity of the tax code, slashing the corporate tax rate doesn't actually affect most U.S. businesses.

Corporate taxes are paid by what are known in tax lingo as C corporations, which include large publicly traded firms like AT&T or Coca-Cola. Most businesses in the United States aren't C corporations, they're pass-throughs. The name comes from the fact that when one of these businesses makes money, the profits are not subject to corporate taxes. Instead, they "pass through" directly to the owners, who pay taxes on the profits on their personal returns. Unlike major shareholders in companies like Amazon, who can avoid taking income by not selling their stock, owners of successful pass-throughs typically can't avoid it.

Pass-throughs include the full gamut of American business, from small barbershops to law firms to, in the case of Uline, a packaging distributor with thousands of employees.

So alongside the corporate rate cut for the AT&Ts of the world, the Trump tax bill included a separate tax break for pass-through companies. For budgetary reasons, the tax break is not permanent, sunsetting after eight years.

Proponents touted it as boosting "small business" and "Main Street," and it's true that many small businesses got a modest tax break. But a recent study by Treasury economists found that the top one percent of Americans by income have reaped nearly 60% of the billions in tax savings created by the provision. And most of that amount went to the top 0.1%. That's because even though there are many small pass-through businesses, most of the pass-through profits in the country flow to the wealthy owners of a limited group of large companies.

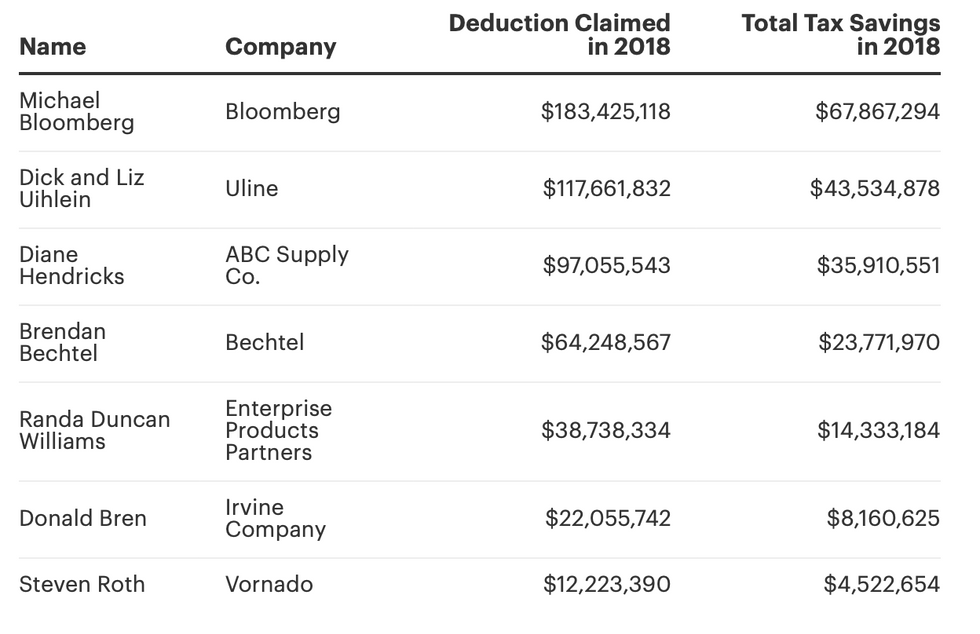

Tax records show that in 2018, Bloomberg, whom Forbes ranks as the 20th wealthiest person in the world, got the largest known deduction from the new provision, slashing his tax bill by nearly $68 million. (When he briefly ran for president in 2020, Bloomberg's tax plan proposed ending the deduction, though his plan was generally friendlier to the wealthy than those of his rivals.) A spokesperson for Bloomberg declined to comment.

Americans With the Highest Income Reaped Most of the Pass-through Tax Break Benefits in 2018

Source: National Bureau of Economic Research studyCredit: Lucas Waldron/ProPublica

Johnson's intervention in November 2017 was designed to boost the bill's already generous tax break for pass-through companies. The bill had allowed for business owners to deduct up to 17.4 percent of their profits. Thanks to Johnson holding out, that figure was ultimately boosted to 20 percent.

That might seem like a small increase, but even a few extra percentage points can translate into tens of millions of dollars in extra deductions in one year alone for an ultra-wealthy family.

The mechanics are complicated but, for the rich, it generally means that a business owner gets to keep an extra seven cents on every dollar of profit. To understand the windfall, take the case of the Uihlein family.

Dick, the great-grandson of a beer magnate, and his wife, Liz, own and operate packaging giant Uline. The logo of the Pleasant Prairie, Wisconsin, firm is stamped on the bottom of countless paper bags. Uline produced nearly $1 billion in profits in 2018, according to ProPublica's analysis of tax records. Dick and Liz Uihlein, who own a majority of the company, reported more than $700 million in income that year. But they were able to slash what they owed the IRS with a $118 million deduction generated by the new tax break.

Liz Uihlein, who serves as president of Uline, has criticized high taxes in her company newsletter. The year before the tax overhaul, the couple gave generously to support Trump's 2016 presidential campaign. That same year, when Johnson faced long odds in his reelection bid against former Sen. Russ Feingold, the Uihleins gave more than $8 million to a series of political committees that blanketed the state with pro-Johnson and anti-Feingold ads. That blitz led the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel to dub the Uihleins "the Koch brothers of Wisconsin politics."

Johnson's campaign also got a boost from Hendricks, Wisconsin's richest woman and owner of roofing wholesaler ABC Supply Co. The Beloit-based billionaire has publicly pushed for tax breaks and said she wants to stop the U.S. from becoming "a socialistic ideological nation."

Hendricks has said Johnson won her over after she grilled him at a brunch meeting six years earlier. She gave about $12 million to a pair of political committees, the Reform America Fund and the Freedom Partners Action Fund, that bought ads attacking Feingold.

In the first year of the pass-through tax break, Hendricks got a $97 million deduction on income of $502 million. By reducing the income she owed taxes on, that deduction saved her around $36 million.

Even after Johnson won the expansion of the pass-through break in late 2017, the final text of the tax overhaul wasn't settled. A congressional conference committee had to iron out the differences between the Senate and House versions of the bill.

Sometime during this process, eight words that had been in neither the House nor the Senate bill were inserted: "applied without regard to the words 'engineering, architecture.'"

With that wonky bit of legalese, Congress smiled on the Bechtel clan.

The Bechtels' engineering and construction company is one of the largest and most politically connected private firms in the country. With surgical precision, the new language guaranteed the Bechtels a massive tax cut. In previous versions of the bill, construction would have been given a tax break, but engineering was one of the industries excluded from the pass-through deduction for reasons that remain murky.

When the bill, with its eight added words, took effect in 2018, three great-great-grandchildren of the company's founder, CEO Brendan Bechtel and his siblings Darren and Katherine, together netted deductions of $111 million on $679 million in income, tax records show.

And that's just one generation of Bechtels. The heirs' father, Riley, also holds a piece of the firm, as does a group of nonfamily executives and board members. In all, Bechtel Corporation produced around $2.3 billion of profit in 2018 alone — the vast majority of which appears to be eligible for the 20% deduction.

Who wrote the phrase — and which lawmaker inserted it — has been a much-discussed mystery in the tax policy world. ProPublica found that a lobbyist who worked for both Bechtel and an industry trade group has claimed credit for the alteration.

In the months leading up to the bill's passage in 2017, Bechtel had executed a full-court press in Washington, meeting with Trump administration officials and spending more than $1 million lobbying on tax issues.

Bechtel met with the Treasury's point man on the tax bill, Justin Muzinich, on pass-through issues in July 2017.

Bechtel also retained a top Washington firm to lobby specifically on pass-through business issues in the tax bill.

Bechtel hired another lobbying firm in the same period.

The chief lobbyist was Marc Gerson, a former top tax lawyer on Capitol Hill.

Amid intense industry lobbying pressure, this phrase was inserted into the bill that extended the lucrative tax break to engineering firms.

Gerson, the lobbyist, later took credit in his law firm bio for winning the tax break for engineering companies.

Thanks to the last-minute insertion into the law, Brendan Bechtel, the company CEO, netted $64 million in write-offs from the tax break in 2018 alone. (A Bechtel spokesperson didn't respond to questions.)

Marc Gerson, of the Washington law firm Miller & Chevalier, was paid to lobby on the tax bill by both Bechtel and the American Council of Engineering Companies, of which Bechtel is a member. At a presentation for the trade group's members a few weeks after Trump signed the bill into law, Gerson credited his efforts for the pass-through tax break, calling it a "major legislative victory for the engineering industry." Gerson did not respond to a request for comment.

Bechtel's push was part of a long history of lobbying for tax breaks by the company. Two decades ago, it even hired a former IRS commissioner as part of a successful bid to get "engineering and architectural services" included in one of President George W. Bush's tax cuts.

The company's lobbying on the Trump tax bill, and the tax break it received, highlight a paradox at the core of Bechtel: The family has for years showered money on anti-tax candidates even though, as The New Yorker's Jane Mayer has written, Bechtel "owed almost its entire existence to government patronage." Most famous for being one of the companies that built the Hoover Dam, in recent years it has bid on and won marquee federal projects. Among them: a healthy share of the billions spent by American taxpayers to rebuild Iraq after the war. The firm recently moved its longtime headquarters from San Francisco to Reston, Virginia, a hub for federal contractors just outside the Beltway.

A spokesperson for Bechtel Corporation didn't respond to questions about the company's lobbying. The spokesperson, as well as a representative of the family's investment office, didn't respond to requests to accept questions about the family's tax records.

Brendan Bechtel has emerged this year as a vocal critic of President Joe Biden's proposal to pay for new infrastructure with tax hikes.

"It's unfair to ask business to shoulder or cover all the additional costs of this public infrastructure investment," he said on a recent CNBC appearance.

As the landmark tax overhaul sped through the legislative process, other prosperous groups of business owners worried they would be left out. With the help of lobbyists, and sometimes after direct contact with lawmakers, they, too, were invited into what Trump dubbed his "big, beautiful tax cut."

Among the biggest winners during the final push were real estate developers.

The Senate bill included a formula that restricted the size of the new deduction based on how much a pass-through business paid in wages. Congressional Republicans framed the provision as rewarding businesses that create jobs. In effect, it meant a highly profitable business with few employees — like a real estate developer — wouldn't be able to benefit much from the break.

Developers weren't happy. Several marshaled lobbyists and prodded friendly lawmakers to turn things around.

At least two of them turned to Johnson.

"Dear Ron," Ted Kellner, a Wisconsin developer, and a colleague wrote in a letter to Johnson. "I'm concerned that the goal of a fair, efficient and growth oriented tax overhaul will not be achieved, especially for private real estate pass-through entities."

Johnson forwarded the letter from Kellner, a political donor of his, to top Republicans in the House and Senate: "All, Yesterday, I received this letter from very smart and successful businessmen in Milwaukee," adding that the legislation as it stood gave pass-throughs "widely disparate, grossly unfair" treatment.

House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Kevin Brady, R-Texas, responded with a promise to do more: "Senator — I strongly agree we should continue to improve the pass-through provisions at every step. You are a great champion for this." Congress is not subject to the Freedom of Information Act, but Treasury officials were copied on the email exchange. ProPublica obtained the exchange after suing the Treasury Department.

Kellner got his wish. In the final days of the legislative process, real estate investors were given a side door to access the full deduction. Language was added to the final legislation that allowed them to qualify if they had a large portfolio of buildings, even if they had small payrolls.

With that, some of the richest real estate developers in the country were welcomed into the fold.

The tax records obtained by ProPublica show that one of the top real estate industry winners was Donald Bren, sole owner of the Southern California-based Irvine Company and one of the wealthiest developers in the United States.

In 2018 alone, Bren personally enjoyed a deduction of $22 million because of the tax break. Bren's representatives did not respond to emails and calls from ProPublica.

His company had hired Wes Coulam, a prominent Washington lobbyist with Ernst & Young, to advocate for its interests as the bill was being hammered out. Before Coulam became a lobbyist, he worked on Capitol Hill as a tax policy adviser for Utah Sen. Orrin Hatch.

Hatch, then the Republican chair of the Senate Finance Committee, publicly took credit for the final draft of the new deduction, amid questions about the real estate carveout. Hatch's representatives did not respond to questions from ProPublica about how the carveout was added.

ProPublica's records show that other big real estate winners include Adam Portnoy, head of commercial real estate giant the RMR Group, who got a $14 million deduction in 2018. Donald Sterling, the real estate developer and disgraced former owner of the Los Angeles Clippers, won an $11 million deduction. Representatives for Portnoy and Sterling did not respond to questions from ProPublica.

Another gift to the real estate industry in the bill was a tax deduction of up to 20% on dividends from real estate investment trusts, more commonly known as REITs. These companies are essentially bundles of various real estate assets, which investors can buy chunks of. REITs make money by collecting rent from tenants and interest from loans used to finance real estate deals.

The tax cut for these investment vehicles was pushed by both the Real Estate Roundtable, a trade group for the entire industry, and the National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts. The latter, a trade group specifically for REITs, spent more than $5 million lobbying in Washington the year the tax bill was drafted, more than it had in any year in its history.

Steven Roth, the founder of Vornado Realty Trust, a prominent REIT, is a regular donor to both groups' political committees.

Roth had close ties to the Trump administration, including advising on infrastructure and doing business with Jared Kushner's family. He became one of the biggest winners from the REIT provision in the Trump tax law.

Roth earned more than $27 million in REIT dividends in the two years after the bill passed, potentially allowing him a tax deduction of about $5 million, tax records show. Roth did not respond to requests for comment, and his representatives did not accept questions from ProPublica on his behalf.

Another carveout benefited investors of publicly traded pipeline businesses. Sen. John Cornyn, a Texas Republican, added an amendment for them to the Senate version of the bill just before it was voted on.

Without his amendment, investors who made under a certain income would have received the deduction anyway, experts told ProPublica. But for higher-income investors, a slate of restrictions kicked in. In order to qualify, they would have needed the businesses they're invested in to pay out significant wages, and these oil and gas businesses, like real estate developers, typically do not.

Cornyn's amendment cleared the way.

The trade group for these companies and one of its top members, Enterprise Products Partners, a Houston-based natural gas and crude oil pipeline company, had both lobbied on the bill. Enterprise was founded by Dan Duncan, who died in 2010.

The Trump tax bill delivered a win to Duncan's heirs. ProPublica's data shows his four children, who own stakes in the company, together claimed more than $150 million in deductions in 2018 alone. The tax provision for "small businesses" had delivered a windfall to the family Forbes ranked as the 11th richest in the country.

In a statement, an Enterprise spokesperson wrote: "The Duncan family abides by all applicable tax laws and will not comment on individual tax returns, which are a private matter." Cornyn's office did not respond to questions about the senator's amendment.

The tax break is due to expire after 2025, and a gulf has opened in Congress about the future of the provision.

In July, Senate Finance Chair Ron Wyden (D-OR)., proposed legislation that would end the tax cut early for the ultra-wealthy. In fact, anyone making over $500,000 per year would no longer get the deduction. But it would be extended to the business owners below that threshold who are currently excluded because of their industry. The bill would "make the policy more fair and less complex for middle-class business owners, while also raising billions for priorities like child care, education, and health care," Wyden said in a statement.

Meanwhile, dozens of trade groups, including the Chamber of Commerce, are pushing to make the pass-through tax cut permanent. This year, a bipartisan bill called the Main Street Tax Certainty Act was introduced in both houses of Congress to do just that.

One of the bill's sponsors, Rep. Henry Cuellar (D-TX) pitched the legislation this way: "I am committed to delivering critical relief for our nation's small businesses and the communities they serve."