Movie Review: ‘The Black Panthers: Vanguard Of The Revolution’ Is Insightful, Timely

By Kenneth Turan, Los Angeles Times (TNS)

LOS ANGELES — Huey P. Newton and Eldridge Cleaver are dead, Bobby Seale is 78, Kathleen Cleaver is 70, the events that turned all of them into national figures are decades in the past. So how is it that The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution comes off as the most relevant and contemporary of documentaries?

Part of the answer is that the social crisis that helped to create the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in the 1960s is still very much with us. You only have to hear a network TV newscaster say nearly half a century ago that “relations between police and Negroes throughout the country are getting worse” to feel a frisson of despair at how up to the minute that sounds.

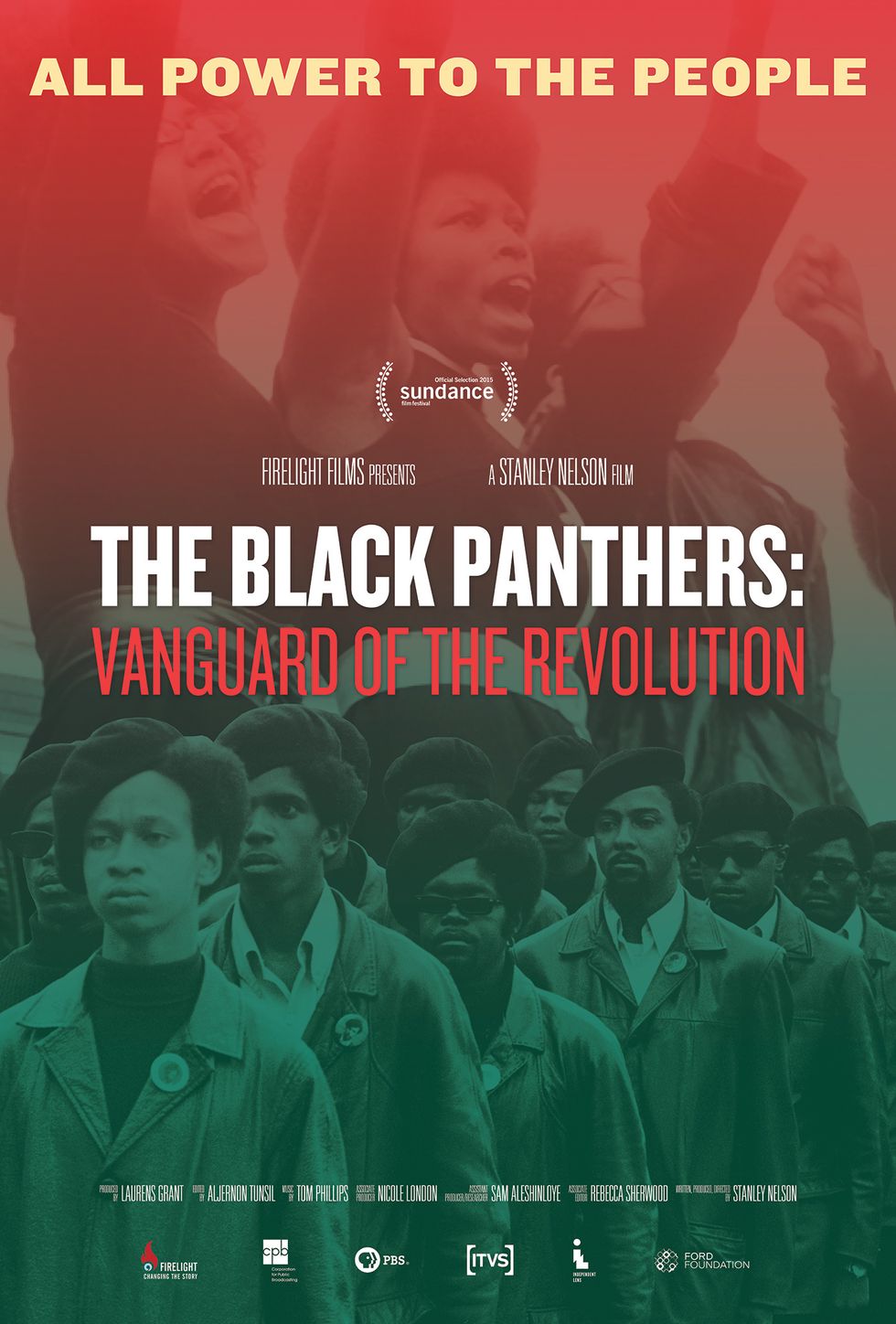

Also a factor is the skill with which writer-director Stanley Nelson has told this story. A veteran documentarian, eight of whose films (including Freedom Summer and The Murder of Emmett Till) have premiered at Sundance, Nelson expertly combines archival footage, photographs, music and his own interviews to assemble the pieces of what is a complicated story.

Nelson understands the play of outsized personalities and unexpected events, and he’s helped that enough time has passed for former Panthers to feel comfortable telling their stories, especially to someone of Nelson’s stature in the documentary world.

Still, none of this was easy, and the Panthers even today remain nothing if not a controversial organization. As former member Ericka Huggins says at the film’s start, “We were making history, and it wasn’t nice and clean. It wasn’t easy. It was complex.”

As if to prove her point, Seale, one of the organization’s founders, did not agree to be interviewed by Nelson, and former party chairwoman Elaine Brown, who did speak, slammed the finished film and asked unsuccessfully to have her interview segments removed.

Despite this brouhaha, the thoughtful approach Nelson takes to the material feels right. He does not look into every skeleton in the organization’s closet, but he doesn’t hesitate to deal with problem areas, including the group’s chauvinism. Though The Black Panthers empathizes with the outrage that brought the party into existence and the pride individual members continue to take in their work, his tone is measured, not incendiary.

Though they evolved into an organization with wide-ranging goals, including decent housing, education, even the dismantling of the capitalist system, the Panthers were started by Newton and Seale as an Oakland self-defense organization dedicated to stopping police brutality. The black panther, Newton said, strikes only if aggression continues.

California gun laws made it legal for citizens to bear arms, and the Panthers got their first publicity break in 1967 when they went to Sacramento to protest a potential change in the statute. When they ended up on the floor of the Legislature (almost by accident, in one account) their black leather jacket and beret look blew people away. As one member recalls, “We had swagger.”

One factor The Black Panthers underscores is how much individual leaders influenced the organization’s actions. Newton was arrested in the shooting death of an Oakland police officer (“Free Huey” became a ’60s battle cry, and he ultimately was released after a hung jury). Writer Eldridge Cleaver, a literary star after writing Soul on Ice, became the face of the party, with mixed results.

As an articulate provocateur whose natural tendency was to escalate a situation, Cleaver’s oratory brought new converts but created other difficulties. “He was a Rottweiler,” says one former member, “an uncontrollable personality.”

While the Panthers worked hard to connect to poor black communities, creating a free breakfast program for schoolchildren that served 20,000 meals a week in 19 communities, their violent rhetoric had made an unswerving, unscrupulous enemy of J. Edgar Hoover, the omnipotent head of the FBI.

Convinced that the Panthers were the biggest threat to national security, Hoover expanded the scope of COINTELPRO, the bureau’s secret counterintelligence division, to include the Panthers and determined to use any means necessary to undermine and destroy the group.

Of all the stories told in Black Panthers, perhaps the saddest is the 1969 death of Fred Hampton, the charismatic 21-year-old chairman of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party who was gunned down by the Chicago police under circumstances so suspicious that a lawsuit brought by the family led to a $1.85 million settlement.

An organization that stubbornly resists being pigeonholed, the Black Panther Party emerges from this documentary with its significance enhanced but some of its tactics questioned. Seeming to speak for the film is Stanford history professor Clayborne Carson. “The leaders,” he says sadly, “were not worthy of the dedication of the followers.”

‘THE BLACK PANTHERS: VANGUARD OF THE REVOLUTION’

No MPAA rating

Running time: 1 hour, 56 minutes

Playing: In limited release

(c)2015 Los Angeles Times. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.