Reprinted with permission from TheWashingtonSpectator.

In January 2018, contractors working for the Department of Homeland Security will begin to fulfill what Donald Trump has promised: building “a big, beautiful wall” that will separate the United States of America from Los Estados Unidos de Mexico. The path of least resistance to breaking ground on the first segment of the controversial border barrier runs through the Santa Ana Wildlife Refuge, 2,080 acres of richly biodiverse federal land on a meandering stretch of the Rio Grande in South Texas.

What has played out in South Texas over the past several months is a prelude to Donald Trump’s larger wall-building project, as the DHS and U.S. Customs and Border Protection play fast and loose with the rules, and muscle anyone who gets in their way.

When site surveying began in the Santa Ana Wildlife Refuge (as first reported in The Texas Observer on July 14), DHS officials had not even filed applications for environmental waivers required to begin construction, a strategy critics described as a conscious attempt to keep the public in the dark. Nor did the department waste any time on cartography, opting instead to replicate maps created by Dannenbaum Engineering, a firm whose lavish contributions to elected officials responsible for approving contracts in South Texas have led to an ongoing investigation by the FBI.

There was no funding for the wall, as surveying proceeded, so Homeland Security officials explained that they were moving money around—most likely from $20 million in unallocated funds DHS announced it has on hand for the current fiscal year—until Congress passes an appropriations bill. But even the likelihood of funding was not assured. Rather than hold an up-or-down vote on $1.6 billion to start construction, House Republicans used a parliamentary tactic that automatically included that amount in the “Make America Secure Appropriations Act,” a four-bill “minibus” that includes defense appropriations.

All this occurred despite warnings from the Democratic leadership that bypassing a vote on funding the wall was unacceptable to the Senate Democratic Conference, which threatened to filibuster unless a discrete vote on the border wall was brought to the floor. But with Trump’s legislative agenda stalled, his approval rating in the low 30s, and every day another bad story about to break, even a small section of border wall would allow him to demonstrate to his base that he can deliver on a key campaign promise.

The politics behind this project are bad, but the policies that undergird it are worse.

The administration in its desperation is effectively constructing a Potemkin wall, a showpiece built to hoodwink a public worried about border security. What critics describe as a “Trump vanity project” will be 2.9 miles of concrete and metal barrier connected to nothing—a freestanding wall on a levee in the middle of a 10-mile gap between two other existing short segments constructed after the Bush administration signed the Secure Fence Act in 2006.

“They are building it here because they can,” Scott Nicol, co-chair of the Sierra Club Borderlands Campaign, told me. Nicol has concluded that because the Trump administration feels the need build something, CPB has set its sights on the tractable Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge. With the exception of the vast Big Bend National Park, 900 miles upriver, most land on the U.S. side of the border is privately owned. Securing right-of-way to build a fence through someone’s cow pasture, sorghum field, oil-and-gas lease, or backyard can take years. Here, on federally owned land, it can be only months.

There are already 110 miles of metal and concrete barrier scattered along the 1,200-mile Texas-Mexico border, built during the Bush and Obama administrations. But this particular section of wall will bisect one of the most biodiverse tracts of land along the Rio Grande. Often referred to as the “crown jewel of the national wildlife refuge system,” the Santa Ana Refuge is home to more than 400 species of birds, two endangered cats (the ocelot and the jaguarundi), and 450 plant species, including one of two rare stands of the threatened Sabal palm tree (the other is in a no-man’s-land behind a stretch of border wall miles downriver near Brownsville).

Wrong Wall, Wrong Place

Approximately 95 percent of anything that might remotely be described as wilderness on the Texas side of the Rio Grande is gone. The Santa Ana refuge was acquired by the federal government in 1943 as part of a string of wildlife sanctuaries along the border. It attracts tens of thousands of visitors each year, including thousands of birders from around the world.

At the heart of the park are four hiking trails that wend their way through mesquite and live oak trees draped with Spanish moss. Taking issue with building this wall in this wildlife sanctuary, The Brownsville Herald noted, “If the wall is built on the levee there, all four trails would be cut off behind the wall and only the visitors’ center and 50 feet of the refuge would be available.” And as a former Parks and Wildlife official told The Texas Observer: “It’s not just the wall, there’s also the cleared border enforcement zone around the wall, the roads, and the light towers.” To add further insult, the wall would shut off public access to La Lomita Chapel, a historic adobe sanctuary built by an order of Catholic priests in 1865.

South Texas, with more than a dozen small towns, a network of state highways, farm-to-market roads, ranch roads, and scores of county roads, has traditionally been a preferred route for undocumented immigrants entering the United States. Yet illegal entries have declined dramatically this year and are at a 17-year low, with 21,659 people turned away or detained at the U.S. ports of entry in June—less than half the number reported in June 2016.

The layout of the wildlife refuge already makes it easy for Border Patrol agents to police. There is a Border Patrol storefront office (which is often closed) at the Santa Ana visitor center. A perimeter road around the sanctuary, which also runs along the levee on which the wall will be built, provides access for Border Patrol agents.

If there were a need for a wall in the wildlife refuge, the regional or local Border Patrol sector chief would have made the case with senior officials in Washington, D.C. As it turns out, that dynamic was reversed. According to Scott Nicol, at a late-July closed-door meeting with stakeholders, Rio Grande Valley Border Patrol Sector Chief Manuel Padilla was asked if he had decided that a wall in the wildlife refuge is a priority. “Padilla paused,” Nicol said, “then Loren Flossman [the Director of the Border Patrol Facilities, who is based in Washington] said that he, in fact, had made the decision.”

Padilla, a 32-year veteran of the Border Patrol who grew up in Nogales, Ariz., was transferred to the Rio Grande Valley in 2015 with a mandate to replicate the success he had achieved in stemming the flow of undocumented border crossers and drugs while he was sector chief in Tucson.

Flossman is a retired Air Force colonel. He has also worked for Science Applications International Corporation, a Reston, Virginia, IT and technical services firm currently under a multiyear, multimillion-dollar contract with DHS. When I contacted him at his personal DHS email account to ask about the criteria he used to select the Santa Ana refuge as a high-priority site for a wall and about potential ethical conflicts related to his years spent at SAIC, Flossman referred me to a DHS public information email address, which does not function. He did not respond to subsequent queries sent to his personal DHS email address.

“Shove the Wall Up Trump’s Ass”

The three Democratic congressmen whose districts include the Texas-Mexico border oppose the wall; Republican Will Hurd, whose sprawling district includes 800 miles of the border but a negligible border population, supports it. (Hurd’s district includes a total of 67,000 residents living in border cities, while McAllen and Brownsville alone, the two largest border cities in the Lower Valley, have a combined population of 277,000.) But Hurd hedges his support, proposing an electronic virtual wall he claims will cost $500,000 a mile, compared to the $24.5 million per mile requested in the government’s 2018 fiscal year budget.

Perhaps by coincidence, construction of the first section of Trump’s border wall will begin in the congressional district of Democratic Representative Filemon Vela, who in 2016 released a letter he had written to then-candidate Donald Trump, in which the congressman wrote: “Mr. Trump, you’re a racist and you can take your border wall and shove it up your ass.” Vela would later tell MSNBC that he would have preferred to have spoken “in more diplomatic language,” but he believed he had to “speak to Donald Trump in language he understands.”

Vela was one of 16 members of the House Hispanic Caucus who signed on to a June 25, 2017, letter to House Rules Committee Chair Pete Sessions (D-Texas), objecting to the self-executing rule, “a legislative gimmick” House Republicans used to avoid “a clean up-or-down vote on [funding for] President Trump’s Border Wall.”

The Republican House leadership used the rule, rather than an amendment, to avoid a vote on the $1.6 billion tucked into the Defense appropriation minibus bill that was sent to the Senate. A spokesperson for Vela told me the Congressman voted against the defense appropriation bill in part because he strongly objected to the parliamentary maneuver used to force the $1.6 billion into the defense-spending bill—to begin construction on a wall he stridently opposes.

The $1.6 billion is a small, initial investment on a much larger project Trump insisted Mexico would pay for, even as he drastically underestimated what the wall will actually cost.

“It’s an easy decision for Mexico: make a one-time payment of $5–$10 billion to ensure that $24 billion [in remittances] continues to flow into their country year after year,” the Trump transition team wrote in a January 2016 memo. The memo also threatened to cut off (illegally) the money that documented and undocumented Mexicans living in the United States send to their families in Mexico.

Since then, Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto has not budged from his position that his country will not pay for a border wall. And estimates of the cost of building a wall along the 2,000-mile border have varied wildly, from Trump’s risible lowball to the price calculated by Senate Committee staffers.

Since threatening Mexico with a cutoff of remittances, Trump has said the wall will cost no more than $12 billion, and that he could build it for $10 billion. House Speaker Paul Ryan and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell predict it will cost $12 billion.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office estimates the wall will cost between $15 billion and $25 billion.

Hurd, while flogging his virtual-wall amendment that has yet to be adopted, said the wall will cost $33 billion. And the Democratic staff of the Senate Homeland Security and Government Affairs Committee extrapolated the per-mile costs in Trump’s first request for funding and published an estimate of $69 billion.

Days later, Trump repeated to the Associated Press that he could build the wall for $10 billion—or less.

Who gets the numbers right? The Democratic Senate staff’s $69 billion is perhaps too high, but Trump’s $10 billion is laughable.

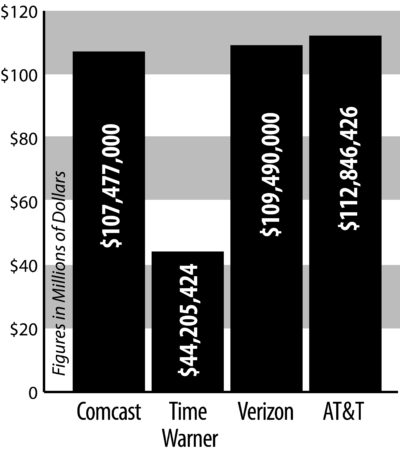

The research offices of the investment firm Alliance Bernstein took an apolitical look at material and labor costs. In a July 2016 “Materials Blast,” published for construction material suppliers and investors, it politely dismissed Trump’s $10 billion estimate.

“The costs to build the ‘easiest’ sections of the existing fence were between $2.8–3.9 million per mile according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office. However, given that these figures exclude labor costs, land acquisition costs and relate to construction in accessible areas with favorable construction conditions, the cost of Trump’s Wall is widely expected to be greater than $15 billion and perhaps as much as $25 billion.”

And as the wall will be built from precast concrete, Bernstein’s researchers surveyed aggregate suppliers along the border and predicted that the biggest two winners could be Mexican companies Cemex and GCG. Cemex has a slight edge because it has plants on both sides of the border.

So Trump’s wall-building project ironically could provide some economic stimulus for Mexico, perhaps even helping to reduce the flow of economic refugees looking for work in the United States.

The Bernstein report concludes:

“As ludicrous as the Trump Wall project sounds (to us at least), it represents a huge opportunity for those companies involved in its construction.”

Meanwhile, border residents brace for a return to the Bush years, when landowners either took what the federal government offered or faced eminent domain condemnation of their property, and the only metric that mattered was “mile count.”

It is a Bush-era law that makes this accelerated pace of wall-building possible. In 2005, California Republican Congressman Duncan Hunter, impatient with the slow progress of a wall project south of San Diego, managed to pass the broadest waiver of law in American history. Hunter’s amendment to the SAFE ID Act allows the Secretary of Homeland Security to waive more than 35 laws—including the National Environmental Policy Act, the Clean Air Act, the Endangered Species Act, the Clean Water Act, the Wilderness Act, and the National Wildlife Refuge System Administration Act—to advance a departmental agenda.

To add muscle to the process, the current minibus appropriation bill includes funding for an eminent domain strike force, a team of attorneys dedicated to seizing private property. (The bill also includes a “deportation strike force.”)

This is the president’s big set piece, as he made clear at his August 22 rally in Phoenix. “If we have to shut down that government, we’re building that wall,” Trump declared. “One way or another, we’re going to get that wall.”

What the dispassionate analysts at an investment firm characterized as “ludicrous” appears to be inevitable.

Lou Dubose is The Washington Spectator’s Senior Political Writer.