Marco Rubio’s Radical Alignment With The Financial Industry

This article originally appeared with the Roosevelt Institute.

Marco Rubio and Jeb Bush have been fighting for months in the GOP primaries to be the candidate representing Wall Street, hedge funds and the financial sector. Headlines like “Bush and Rubio race for Wall Street cash” dominated the fall coverage of their campaign, right next to headlines like “Donald Trump terrifies Wall Street” with statements like “hedge fund guys didn’t build this country. These are guys that shift paper around and they get lucky.”

With Bush dropping out of the race this weekend, Rubio has won this contest. And with Bush leaving, anyone carrying a quasi-reformist message on the financial sector is also gone. Rubio is both much more in sync with finance on specific issues, and also far more ideologically extreme on issues surrounding the financial sector than Jeb Bush was.

Rubio now is the establishment consensus candidate and the best hope of stopping Trump for the GOP. This framing and coverage will mask how extreme Rubio’s agenda is. As Matt Yglesias describes, he’s running on “a platform of economic ruin, multiple wars, and an attack on civil liberties that’s nearly as vicious as anything Trump has proposed.” This also extends to finance, especially when compared against Bush on the financial crisis, Dodd-Frank, vulture funds, the Federal Reserve and taxes. According to Rubio…

The Crisis was Government’s, Not Wall-Street’s, Fault

Going back years, Rubio has a been a big proponent of the idea that government policies, usually ones associated with GSE goals, were responsible for the housing bubble and financial crisis (“In fact, a major cause of our recent downturn was a housing crisis created by reckless government policies”).

This argument is what Barry Ritholtz calls The Big Lie, and it’s the kind of argument that has the American Enterprise Institute denouncing the movie The Big Short as fiction. Here’s a summary of why this argument is wrong. For our purposes, less extreme conservatives have danced around this issue without trying to quash it. Keith Hennessey, Douglas Holtz-Eakin and Bill Thomas refused to endorse it while dissenting in the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission. Robert VerBruggen politely tries to throw cold water on it without actually burying it at RealClearBooks (this argument is “harder to believe, if ultimately nondisprovable”).

This may seem like an esoteric, academic debate, but if Wall Street played no role in the crisis, then there’s no need for any reforms. Which is where Rubio ends up.

Repeal Dodd-Frank with No Replacement

Jeb Bush has argued that he would repeal Dodd-Frank if he could, but he was also promoting a plan for how to weaken and replace parts of it in accordance with conservative goals. He argued for more capital requirements for the largest banks (“What we ought to do is raise the capital requirements so banks aren’t too big to fail”) while weakening them for smaller firms. He wanted to target the management and funding structures from the CFPB for dismantling, and be harder on the regulators in general. It was easy to see Bush converging to the position of someone like Rick Perry, who had the most detailed (but still very general) outline for how he’d tackle regulating Wall Street, an outline that involved weakening Dodd-Frank rather than strictly repealing it.

Rubio has no financial reform plans. There are 36 [!] detailed “policy issues” on his website, and not a single one is related to financial reform. For someone who is trying to be the ideas-driven candidate, there’s simply nothing about how to regulate Wall Street. There’s simply a press release saying: “We need to repeal Dodd-Frank,” which he has voted to do numerous times. Each time he’d replace it with nothing. He is vocal in his policy issues section about having a plan to replace Obamacare after repeal; he has no such plan for Dodd-Frank. This makes perfect sense if you have a very distorted view of what happened in the crisis, one where Wall Street simply didn’t matter.

When we do find specifics, they are either more in sync with financial interests directly or reflect an extreme ideology far outside most conservatives’ points of view. This is clear when you compare it to Jeb Bush.

No Bankruptcy for Puerto Rico

Jeb Bush has argued that Puerto Rico, facing a debt crisis exacerbated by holdout vulture hedge funds, should be able to access bankruptcy. Marco Rubio argues they should not. As Casey Tolan of Fusion notes, according to “public campaign-finance documents, at least six executives of hedge funds that hold Puerto Rican debt have donated to Rubio’s presidential campaign.” According to the New York Times, Rubio “expressed interest this year in sponsoring bankruptcy legislation for the island […] Mr. Rubio’s staff even joined in drafting the bill. But this summer, three weeks after a fund-raiser hosted by a hedge-fund founder, Mr. Rubio broke with those backing the measure.” This is consistent with a much larger AstroTurf and lobbying campaign being waged by hedge funds and financial firms.

This is a very strong stance, one I believe no other person who has run for the 2016 nomination has taken. It’s also one that aligns with both the practical interests of the hedge funds and their ideological assertion that creditors must be paid in full no matter how much it destroys Puerto Rico, or any other place.

Austere Reworking of the Federal Reserve

But this is nothing compared to the Federal Reserve. Rubio has said that it’s “not the Fed’s job to stimulate the economy,” when that is exactly what a crucial part of the Federal Reserve’s job is. He went on to say that the Fed’s “job is [to] provide stable currency and I believe [it] should operate on a rules based system. They would have a very simple rule that determines when interest rates go up and when interests rates goes down.”

Changing the Federal Reserve to a single mandate for stable currency, and not for full employment, is something Rubio has advocated since at least 2012. The appointments he’d place on the Federal Reserve would follow this, naturally, radically changing the nature of financial markets to terms far more favorable to those who only care about inflation. Note that this isn’t about “auditing” the Fed, or better governance reform, or an argument that policy should be tighter than it is, which are all things people are currently fighting about when it comes to the Federal Reserve. This would be a massive change to the mission of the Fed, one that would empower the financial industry, since it would align monetary policy directly with its interests and disempower anyone who cares about full employment.

I can’t find anything about Jeb Bush taking extreme opinions on the Federal Reserve and neither could other people looking for it. It’s certainly not the major focus it is for Rubio. No doubt Bush would have been more hawkish than the current situation, but being more hawkish and what Rubio wants to do are totally different projects.

Eliminate Taxes For Capital Owner

Marco Rubio’s original family-friendly tax cut policy was quickly expanded once questioned by the guardians of conservative supply-side orthodoxy. Most notably, he would eliminate all taxes on incomes from capital gains and dividends. This income from holding financial assets is incredibly concentrated at the top. As Josh Barro notes, Rubio’s tax plan “would raise incomes for the top one-thousandth of taxpayers by 8.9 percent — that is, an average tax cut of more than $900,000 per year — because of its sharp cuts in tax rates on business income and capital income.”

Besides the massive distributional implications, this has consequences for finance’s power over the real economy. A lot of people are looking at the influence of the financial sector and the issue of “short-termism,” or the extensive prioritization of dividend and buyback payments to shareholders over real investments. Independent of its effects in driving inequality, Rubio’s removal of any taxes on dividends and capital gains would certainly scale this issue. As Danny Yagan has found, the substantial cuts to dividends passed by the George W. Bush administration didn’t boost investment. It did, however, boost dividends, something other research in finance has found. If you are worried that corporations prioritizing payouts instead of investments is a challenge to our economy, taking the extreme act of eliminating taxes on dividends and capital gains would send that spiraling.

The establishment “lane” has gone to Marco Rubio. We’ll soon find out if he’s capable of beating Donald Trump. But either way, that lane has become far more radical, and far more in sync with financial wealth, than anyone should have expected a year ago.

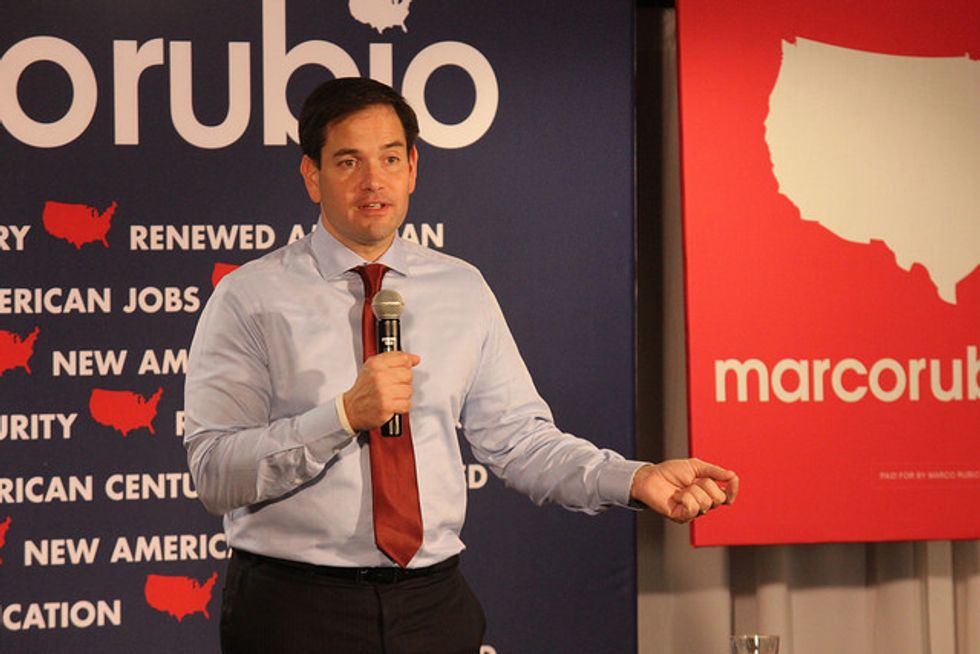

(Image via: Matt A.J.)