A Definitive History Of Trump Steaks

This article was originally published on ThinkProgress.

In all the name-calling surrounding Donald J. Trump, the current Republican presidential front-runner and likely nominee, there’s one title that, until very recently, was rarely applied: steak salesman.

“Ever heard of Trump steak or Trump vodka?” Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL) asked during the most recent Republican debate. “Take a look at Trump Steaks. Trump Steaks is gone. You have ruined these companies.”

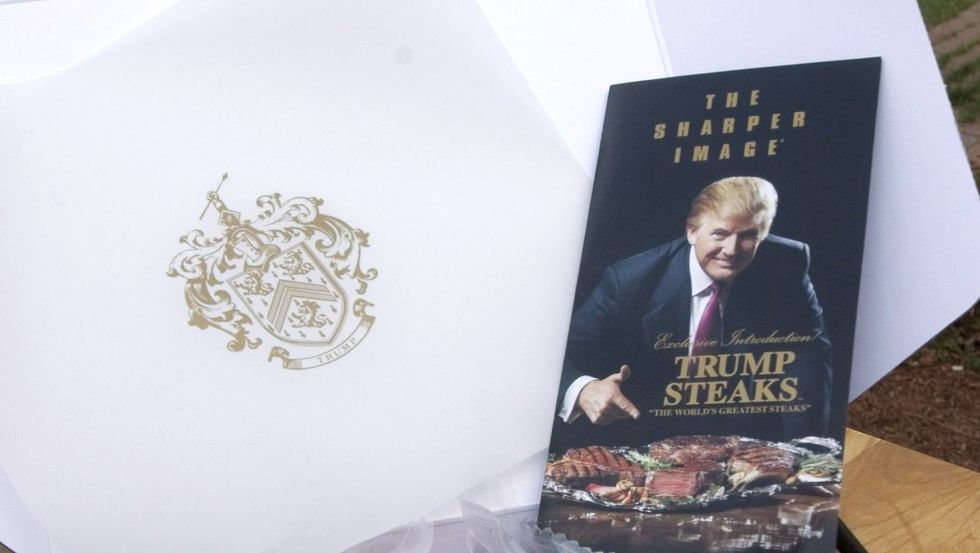

It is true that Trump is no longer a frozen steak salesman. That venture — Trump Steaks — was brief, lasting in earnest for just two months in the summer of 2007 as part of an agreement with the Sharper Image, that late-aughts mall store perhaps best known for electric massage chairs and double wine chillers. But in recent months, Trump’s brief tenure as a frontman for a line of frozen steaks has resurfaced in the public imagination.

There’s not much left of Trump Steaks — you can’t order them anymore, and the websites that once sold the frozen meat slabs are now relegated to the internet archives. But as Trump continues to hurtle towards the Republican nomination and, perhaps, the presidency, it’s worth looking back at exactly how a man who so consistently brags about his intelligence and business acumen failed to sell steaks to one of the most beef-obsessed countries in the world.

Raising The Steaks

As Americans try to make sense of the man that could someday be president, there seems to be a renewed interest in Trump’s lessethose r-known business ventures. According to Google Trends, which tracks how much people on the internet are searching for a certain term, searches for Trump Steaks have shot up in the last month, reaching an all time high in March.

When you type Trump Steaks into Google, the second hit is the commercial spot that ran in conjunction with the steak’s sale. It features a besuited Donald Trump sitting in front of a gallery wall of framed Trump paraphernalia — what looks like a photo of Trump Towers, a portrait of Trump and his children, and a third image blurred from vision save for the large letters “T-R-U-M-P” in the uppermost corner of the screen. Behind Trump’s right shoulder, stacked like the suitcases full of money on a Howie Mandel gameshow set, are boxes with “Trump Steaks” stamped in gold.

Steaks were not Trump’s first foray into the food industry. By the time Trump Steaks hit the market in late spring of 2007, Trump had already stamped his name on both Trump Vodka, which was released to much fanfare in 2006, and Trump Ice, his proprietary brand of bottled water, which launched in 2005.

But if selling steaks still seems like an illogical move for the Trump brand, consider, for a moment, the Trump brand — hyper-masculine, decadent, built on the back of luxury real estate, hotels, and casinos. All those properties — especially the casinos and the hotels — boasted restaurants, and those restaurants needed to source their steak from somewhere.

So Trump struck up a relationship with Buckhead Beef, a specialty meat company that was purchased by Sysco, the largest marketer and distributor of food service products in the United States, in 1999. According to Jack Serratilli, a Buckhead Beef sales manager, Trump first approached the company when he opened his first casino in Atlantic City. Buckhead had already been servicing other casinos in Atlantic City, supplying beef for their restaurants, and they began to do the same for Trump.

Beginning around the mid-2000s, however, Trump’s Atlantic City projects began to suffer financial blows, culminating, eventually, in a 2004 Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing. According to the filing, Trump Hotels owed Buckhead Beef $715,240, related to their partnership with the casino.

Two years later, on August 6, 2006, Trump filed an application to trademark Trump Steaks. A few months later, in October, the New York Inquirer published a story reporting that Trump had entered into a partnership with Buckhead Beef to sell the steaks. The now-trademarked Trump Steaks name was first used in commerce, according to filings made to the United States Patent and Trademark Office, in December 2006. To start, it appears as though Trump sold his steaks through a direct sales website, housed at www.trumpsteaks.com.

‘We Literally Sold Almost No Steaks’

A few months later, a licensing executive with the Trump Organization approached Jerry Levin, CEO of the Sharper Image. The Trump Organization had been looking for a place to sell their newly trademarked steaks, and the executive, who was a good friend of Levin’s, thought that the product could be an interesting fit for the stores, which until that point had been better known for electronics than food products.

The idea of selling steaks, even those bearing the Donald Trump name, seemed instantly odd to Levin.

“The idea was certainly an unusual one,” he said, calling the connection between Trump Steaks and the Sharper Image “truly a non sequitur.” Levin explained that the licensing executive likely picked the Sharper Image because he and Levin had a pre-existing relationship (though Trump, in the sales commercial, refers to Sharper Image as “one of [his] favorite stores, with fantastic products of all kinds).

“I asked, ‘What is it they want us to do?’” Levin recalled. “And they really only had two criteria to the licensing agreement itself: Donald wanted his picture on the front of a Sharper Image catalog when we introduced this, and he wanted his picture in every one of our stores when we introduced it.”

But the Sharper Image was on the brink of some massive changes. Levin had been brought in about a year and a half earlier to try and buoy the company, which had been experiencing adownturn in sales — before Levin was instated, the company had seen six quarters of declining sales, claiming a net loss of $15.6 million for the 2005 fiscal year.

Levin described the licensing agreement as “unique,” noting that it lacked the kinds of things he had seen in traditional agreements, like minimums, which would have required the Sharper Image to pay the Trump Organization a set amount regardless of how many steaks they sold.

“We had no real expectations in terms of this thing working because it was so out of the box,” Levin said. “I didn’t invest any money in it, at all. I would be surprised if I invested $25,000 in this whole thing. We set up the logistics, they did all the work. We were just an agent to sell them, really.”

The Trump Organization did not return ThinkProgress’ request for comment, and Cathy Hoffman Glosser, the former licensing executive for the Trump Organization during the time of Trump Steaks, refused to comment.

According to Levin, the Sharper Image and the Trump Organization solidified the deal in the spring of 2007, a few months before Trump Steaks made their public debut in conjunction with the Sharper Image. But despite the strange nature of the licensing agreement, and the fact that the Sharper Image put barely any of their own resources behind the product, Levin remembers the launch party for Trump Steaks, which took place on May 8, 2007, at the Sharper Image in Rockefeller Center, as a press frenzy.

“I’d never seen more people show up for a press event in my life,” he said. “It was jammed. Everybody came from every segment of the media.”

Reporters from Home magazine, Gourmet magazine, People, New York Daily News, and Every Day with Rachael Ray showed up to the launch, which featured speeches by both Levin and Trump. Trump took the opportunity to boast of the steaks’ quality, telling reporters that the product was going to be a boon for the company, equivalent to Trump Vodka, which had launched just a year earlier.

“Trump Vodka which has been so successful… it’s the number one new launch since many years, over 100,000 cases,” Trump said. “I think this is going to be exactly there.”

The product officially launched with the Sharper Image’s 2007 June catalog, which featured a grinning Trump pointing at a tray full of his steaks. At the same time, the Sharper Image placed huge posters of Trump in the windows of its 185 stores nationwide.

The steaks were only available for mail order, and ranged from the Classic Collection, which cost customers $199 for two filet mignons, two cowboy bone-in rib-eyes and 12 burgers, to $999 for 24 burgers and 16 steaks.

But despite the rash of media attention, Levin said, the steaks just didn’t sell.

“The net of all that was we literally sold almost no steaks,” Levin said. “If we sold $50,000 of steaks grand total, I’d be surprised.”

For the Sharper Image, however, the campaign actually brought in business. Levin recalled getting calls from regional managers, who told him that customers would come into the store to ask why they had a picture of Donald Trump in the window, and end up buying another one of the Sharper Image’s products.

“Our sales in Sharper Image from that period went up dramatically, and we made millions of dollars,” he said.

After two months of poor sales, the Sharper Image pulled the steaks. Levin said that he can’t speculate whether Trump lost any money on the venture, since it likely resulted in higher brand recognition for the Trump Organization, but he did call it a “a bad business idea.”

“What it cost them to do this, I don’t know. But it was an exercise in branding,” he said. “I don’t know if that’s what he had in mind for the beginning.”

‘Edible, But Not Particularly Good’

It’s hard to say exactly what made Trump Steaks such a poor seller. It could easily be that the Venn Diagram of consumers looking to buy hundreds of dollars worth of frozen steaks and shoppers at the Sharper Image has little to no overlap.

But it’s also a possibility that the steaks just weren’t that good — or at least not worth the $200 to $900 dollars, or roughly $50 a pound, by some estimates — that customers were asked to shell out for the pleasure of dining like Donald Trump.

What they were promised, by Trump himself, was “the world’s greatest steaks… in every sense of the word” and “by far the best-tasting most flavorful beef” they’ve “ever had.”

Reviews of Trump’s Angus Beef Steakburgers, which still exist on QVC.com, tend to contradict this. One reviewer called it the “Worst Burger EVER!!” complaining that it was “nothing but grease.” Another reviewer called them “extreemly [sic] greasy,” and another reviewer wrote that they were “really greasy, have no flavor, over-priced and just gross!!” According to a recent article on Death and Taxes, which looked at all of the customer reviews still online at QVC.com, “more than 50 percent were highly negative 1-2 star reviews.”

Not all reviews of Trump Steaks were bad. Sharon Dowell, former food editor for the Oklahoman, called the steaks “tender, juicy and absolutely among the best-tasting steaks I’ve cooked on my home grill.” The New York Post gave them a 7.5 out of 10, noting that it was “an undeniably good steak” — but still three times the price of another steak that they gave a 7 to in the same taste test. Gourmet, in their taste test, were less effusive, calling the steaks “edible, but not particularly good.”

Martha Stewart, however, had perhaps the most unique response to Trump Steaks. In an interview with Joan Rivers, the lifestyle mogul and former Apprentice contestant replied “Too bad!” when Rivers said that the steaks weren’t actually from a slaughtered Donald Trump.

The Greatest Steaks In The World?

Unfortunately, interested parties can no longer order a $200 box of Trump Steaks to test for themselves whether they are truly remarkable steaks. But there are a few clues that can help parse out whether these frozen slabs of meat really were the greatest thing in the entire world.

To start, let’s look at the certification — all of the steaks sold as Trump Steaks were Certified Angus, and USDA Prime. According to the Sharper Image’s press materials from the launch, Certified Angus USDA Prime is “the pinnacle of the grading scale for traits that determine beef’s tenderness, juiciness and flavor.”

Those distinctions, however, might not tell the whole story about the quality of a particular cut of beef.

“I never tasted a Trump Steak, but so many of the marketing programs that we have are empty vessels that don’t mean a lot,” Mark Schatzker, author of Steak and The Dorito Effect, said. “They are all selling the same thing — commodity beef at a certain grade.”

Certified Angus, Schatzker explained, refers primarily to the fact that a cow must be 51 percent black hided — that is, 51 percent of a cow’s fur has to be black. That’s because most Angus cattle are black, and that gives certifiers an easy way to quickly weed out cattle that probably don’t have any Angus genes in them. But there are a few problems with that thinking, Schatzker explained.

“Other cattle, besides Angus, are black,” he said. “It’s a little bit like saying that if a car is 51 percent red it’s a certified Ferrari.”

And not all Angus are black. There’s a breed of Angus known as Red Angus that, Schatzker says, some beef purists think is actually of a higher quality than Black Angus — but Red Angus don’t qualify to be Certified Angus.

The meat from a Certified Angus cow also has to exhibit modest or higher marbling (fat), as well as fine marbling texture. It also has to come from young cows — between 9-30 months old. That’s a problem, Schatzker says, because young cows tend to have less flavor — think of the way that a mild veal tastes compared to a steak.

USDA Prime, a certification given by the USDA, also focuses largely on marbling.

“Like the Angus certification, it’s based on the idea that you can tell how a steak is going to taste by looking at it,” he said. “You can’t.”

Trump Steaks’ 100-percent grain finish also probably didn’t help boost their quality, according to Schatzker. Livestock operators will often finish a cow on grain to fatten them quickly before slaughter. It’s a technique that helps create a more marbled beef, but trades quick fattening for deep flavors.

“If you compare a lightly-marbled grass fed steak to a highly-marbled grain fed steak, the marbling is in no way an indicator of flavor or eating quality,” he said. According to Schatzer, grain-fed beef might be juicer, or have more fat, but it tends to give off a greasy mouthfeel that he finds unappealing.

From Selling Steaks To Selling Policies

Trump Steaks have been off the market for almost a decade — but the tricks Trump used to sell them, slapping his name and superlatives on a demonstrably average product, are still very much around.

Take, for example, Trump’s stance on military policy. In a September interview with conservative radio host Hugh Hewitt, Trump bragged that “I will be so good at the military your head will spin.” Which sounds really appealing — the president is, after all, the commander-in-chief of the nation’s military, so naturally it would be good to have strong skills in that arena. But Trump made that statement just moments after confusing the Iranian Quds Forces of the Revolutionary Guard and the Kurds, the fourth-largest ethnic group in the Middle East. Slapping a superlative on your military expertise doesn’t make you good at foreign policy, just like calling a Certified Angus Prime steak “the greatest steak in the world” doesn’t make it the greatest steak in the world.

Or consider the way he markets his skills as a job creator. In his June speech announcing his presidential campaign, Trump said that he would be “the greatest jobs president that God has ever created.” But when the Associated Press asked economists whether Trump’s policy details would actually bring jobs back from overseas, they called it “implausible.”

And yet, with every primary or debate, Donald Trump inches closer to the Republican nomination and the presidency. He may not have been able to sell steaks to American consumers, but this time around, Trump seems to be having a lot of success selling his disjointed policies to Republican voters.