Gov. Jerry Brown’s Link Between Climate Change And Wildfires Is Unsupported, Fire Experts Say

By Paige St. John, Los Angeles Times (TNS)

COWBOY CAMP, Calif. — The ash of the Rocky fire was still hot when Gov. Jerry Brown strode to a bank of television cameras beside a blackened ridge and, flanked by firefighters, delivered a battle cry against climate change.

The wilderness fire was “a real wake-up call” to reduce the carbon pollution “that is in many respects driving all of this,” he said.

“The fires are changing. … The way this fire performed, it’s not the way it usually has been. Going in lots of directions, moving fast, even without hot winds.”

“It’s a new normal,” he said in August. “California is burning.”

Brown had political reasons for his declaration.

He had just challenged Republican presidential candidates to state their agendas on global warming. He was embroiled in a fight with the oil industry over legislation to slash gasoline use in California. And he is seeking to make a mark on international negotiations on climate change that culminate in Paris in December.

But scientists who study climate change and fire behavior say their work does not show a link between this year’s wildfires and global warming, or support Brown’s assertion that fires are now unpredictable and unprecedented. There is not enough evidence, they say.

University of Colorado climate change specialist Roger Pielke said Brown is engaging in “noble-cause corruption.”

Pielke said it is easier to make a political case for change using immediate and local threats, rather than those on a global scale, especially given the subtleties of climate change research, which features probabilities subject to wide margins of error and contradiction by other findings.

“That is the nature of politics,” Pielke said, “but sometimes the science really has to matter.”

Other experts say there is, in fact, a more immediate threat: a landscape altered by a century of fire suppression, timber cutting and development.

Public attention should be focused on understanding fire risk, controlling development and making existing homes safer with fire-rated roofs and ember-resistant vents, said Richard Halsey, who founded the Chaparral Institute in San Diego.

Otherwise, he said, “the houses will keep burning down and people will keep dying.”

“I don’t believe the climate change discussion is helpful,” Halsey said.

Brown does not contend that climate change alone is making California’s fires worse, said Nancy Vogel, spokeswoman for the governor’s Natural Resources Agency. But she said addressing fires in the same breath as global warming “broadens the discussion and encourages us to think about the future.”

___

Brown’s senior environmental adviser, Cliff Rechtschaffen, has said the governor believes climate change is not regarded with sufficient urgency and should be addressed “on a World War III footing.”

At a U.N.-sponsored panel on air pollution in September, Brown again linked wildfires and global warming.

“In California, our forest fires are more frequent, (of) greater magnitude and display completely unique characteristics,” the governor said. “We’re already being affected by climate change.”

But climate scientists’ computer models show only that global warming will bring consistently hotter weather in future decades. Their predictions that warming will bring more forest fires — mostly in the Rockies and at other higher elevations, while fires may actually decrease in Southern California — also are for future decades.

Even in a warmer world, they say, land management policies will have the greatest effect on the prevalence and intensity of fire.

A study published in August by a Columbia University team led by climatologist Park Williams concluded that global warming has indeed shown itself in California, by increasing evaporation that has aggravated the current drought. But Williams said his research, the first to tease out the degree to which global warming is affecting California weather, did not show climate change to be a major cause of the drought.

Even climate ecologists who describe a strong tie between fire frequency and weather say they cannot attribute that connection to phenomena beyond normal, multi-decade variations seen throughout California history.

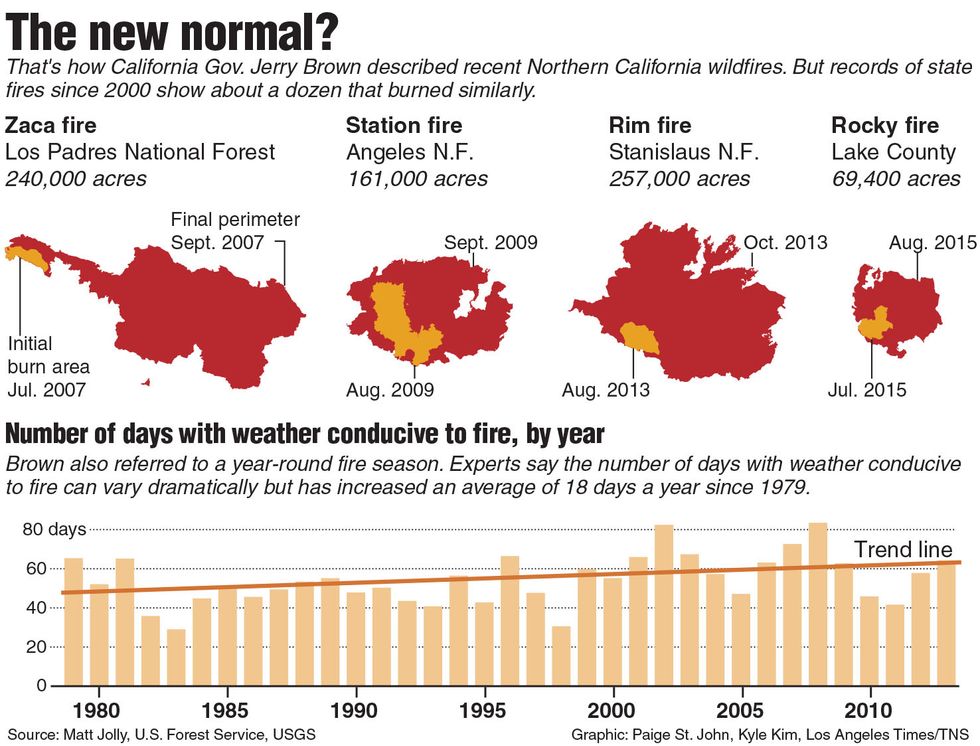

“There is insufficient data,” said U.S. Forest Service ecologist Matt Jolly. His work shows that over the last 30 years, California has had an average of 18 additional days per year that are conducive to fire.

In addition, predictions of the impact that global warming will have on future fires in California vary.

A team of researchers at the University of California, Irvine recently reported that in 25 years, climate change will increase the size of fires driven by Santa Ana winds in Southern California. But their models varied on how much increase to expect: from 12 percent to 140 percent.

Predictions from a UC Merced expert include a possible decrease of such fires as dry conditions slow vegetation growth.

Today’s forest fires are indeed larger than those of the past, said National Park Service climate change scientist Patrick Gonzalez. At a symposium sponsored by Brown’s administration, Gonzalez presented research attributing that trend to policies of fighting the fires, which create thick underlayers of growth, rather than allowing them to burn.

“We are living right now with a legacy of unnatural fire suppression of approximately a century,” Gonzalez told attendees.

The Rocky fire, which began in late July in Lake County, spread quickly through mature chaparral in the Cache Creek Wilderness, creating tall plumes that sucked in air from all directions.

California fire records analyzed by the Los Angeles Times show a dozen similar fires from 2000 to 2014 that each moved quickly, spreading at more than 1,000 acres an hour. A few were driven by the notorious Santa Ana winds, but most were similar to the Rocky fire and three other fast-moving Northern California fires that followed it.

Fire behavior specialist Jeff Shelton, who provided daily forecasts for the Rocky fire and, later, the Jerusalem fire, said he could not attribute their behavior to climate change. He cited the summer’s dry weather, an abundance of fuel created by a lack of previous fires, and steep slopes that allowed the fires to spread quickly.

Ecologists said their behavior was typical of natural chaparral fires, which burn infrequently but intensely.

A regional staff member in Brown’s emergency operations office called the fires “unprecedented,” a description then used by the administration for other conflagrations.

But those burns were classic plume-dominated convection fires, fed largely by an abundance of combustible material, fire scientists said.

“They are more and more common because we have more and more fuels,” said Joaquin Ramirez of Technosylva, an international fire modeling company based in San Diego.

___

A month after Brown’s visit to Cowboy Camp, a team of federal wildland managers and a chaparral researcher met at the spot and climbed to the ridge where the Rocky fire had made a 20,000-acre run in one afternoon and night.

Charred burls in the lower lands already had spurted bright green growth. Water would soon spring from dry creek beds, like a Biblical miracle, as the aquifer rose without vegetation to suck it down.

Bureau of Land Management fire manager Jeff Tunnell surveyed the mosaic of black stubble against untouched silvery green stands of manzanita and chamise, oak and pine. A fire had been due.

“One hundred years of fire suppression is building fuel beds,” Tunnell said. “Almost any year can produce a fire like this one.”

___

WHAT DOES ‘WEATHER’ REALLY MEAN?

Weather, drought and climate mean different things:

Weather: conditions of the atmosphere over a short period of time, up to months

Drought: a year or more of below-average rainfall

Climate: patterns of weather over a long period, usually 30 years or more

Source: NASA

Graphic: Graphic of wildfires in recent California history. Los Angeles Times 2015