Reprinted with permission from The American Prospect.

“That’s not who we are,” Barack Obama often says when appealing to Americans to oppose illiberal policies such as torturing prisoners, barring immigrants on the basis of their religion, and denying entry to refugees. But now that Americans have elected a president who has called for precisely those policies, Obama’s confidence about who we are may seem misplaced. Questions about the defining values of our common nationality have haunted us before at critical moments in American history, and now they do again: In the wake of Donald Trump’s election, what does it mean to be an American? Will Trump and Republican rule change not just how the world sees us but our self-understanding?

National elections create a picture of a people, and they send a signal about changes the voters want. The picture and the signal may be distorted and subject to interpretation, but they cannot be ignored. The 2016 election left many people angry at pollsters for failing to predict the outcome, but it revealed a more serious misapprehension among Democrats and on the left about the future. Eight years earlier, Obama’s victory had seemed to demonstrate the historical inevitability of a more diverse and progressive America, and his reelection seemed to confirm it. Yes, Republicans had their base, but it was old and nearly entirely white. Misleading but widely influential demographic forecasts indicated that the United States was destined to become a majority-minority society. The growing acceptance of LGBT rights, especially among the young, suggested that the cultural backlash against the 1960s was receding. Political analysts interpreted demographic and cultural changes as ushering in an inexorable social and political shift that would favor Democrats and that Republicans would have to accommodate.

We cannot be certain that the arc of the universe ultimately bends toward justice, but we do know that for long periods it has been bent the other way.

A historical perspective should have urged caution. Progressive changes have been arrested before. Alongside the civic, universalistic conception of American identity—the idea that people of any race and religion can come from anywhere in the world and be fully American—there has always been an exclusive view of the country’s core identity as white and Christian. When Americans imbued with that understanding have felt under threat, they have struck back. We cannot be certain that the arc of the universe ultimately bends toward justice, but we do know that for long periods it has been bent the other way. After Reconstruction in the 19th century and the civil-rights struggle a century later, the South—the white South—did rise again. Nothing is guaranteed politically by changes in demography, economics, or culture. Every battle for justice and equality must be fought again and again.

So Trump’s victory may not be the “last gasp” of an old and dwindling white majority. It threatens instead to be a tipping-point event. Although the outcome hung on only a sliver of the electorate in three states, it may produce a disproportionate swing of power to the right and a remaking of American society. Only concerted political action—informed by an accurate understanding of our national situation—can stop that from happening.

The Shock of Two Impossibilities

Before Obama’s election, a black man as president had seemed an impossibility, and before the 2016 primaries, Trump as a major-party nominee, let alone as president, had also seemed an impossibility. Historians decades from now will be asking how these two impossibilities followed one another in immediate succession. If elections create a picture of a people and send a signal about the changes voters want, Americans could not have created two more different pictures of themselves and sent two more different signals than they have now.

When the improbable happens, we may have just gotten the odds wrong. When what we believed to be impossible happens, it tells us we were wrong in a more fundamental way, in this case about our fellow citizens. The victories of Obama and Trump, however, sent two conflicting error messages about who we are.

Obama’s victory seemed to demonstrate that, contrary to what we may have thought, the greatest shame in our history might finally be history. Perhaps the American people were willing to judge a man by the content of his character rather than the color of his skin. To those who rejoiced at that thought, Obama’s election was not just a hopeful sign of racial healing but an act of national redemption. It was an event, moreover, of global significance, promising a renewal of America’s reputation for equality and decency in the eyes of the world, a fitting culmination of an era of sweeping worldwide change. Hadn’t the Berlin Wall fallen and South African apartheid ended? Obama’s presidency was one more sign of the triumph of tolerance, pluralism, and democracy.

It would be easier to make sense of Trump’s victory if Obama had become unpopular and the voters were repudiating his administration. As of November, however, Obama enjoyed a healthy approval rating. Nonetheless, Americans elected the very man who spread the birther lie about Obama and came to epitomize the hard-right view that his presidency was illegitimate.

Perhaps Trump’s election shouldn’t have been a surprise. The antecedents can be found in the radicalization of the Republican Party in recent years, and the parallels can be found in the resurgent combinations of populism, xenophobia, and oligarchy in other countries. But Trump’s triumph was shocking because he acted so often in ways that would have sunk any other candidate. He didn’t just disregard the norms of civility, for example, by bragging about the size of his penis and insulting leaders of his own party. He openly appealed to prejudice when he denounced the Indiana-born judge in the Trump University case as a “Mexican” and called for a ban on Muslim immigrants. As he had with the birther lie, he resorted to obvious and outrageous falsehoods such as the claim that Ted Cruz’s father had been involved in John F. Kennedy’s assassination (or the more recent lie that millions voted illegally for Hillary Clinton). He violated the norms of democracy by encouraging violence against protesters at his rallies and refusing to say before the election that he would accept the results.

Trump’s brazenness didn’t just reveal who he is and how he might govern. Of course, we shouldn’t project all Trump’s views onto all those who voted for him. But when Trump’s statements and actions didn’t prove disqualifying, they revealed something first about the Republican Party and then about the voters in November who chose him as president. This was the real shock: Trump’s ability to get away with violating norms against incivility, violence, prejudice, and lying told us something that we didn’t know, or may not have wanted to believe, about America itself.

Which American Story?

Successful political leaders usually offer a narrative about their country and the world that encourages voters to see them in command. The story about America told by Trump has deep historical roots, though it is fundamentally different from one that Ronald Reagan, the Bushes, the Clintons, and Obama have been telling. Trump’s story is nationalistic, inward-looking, dark, and divisive but well-calculated to mobilize a coalition of the resentful and the opportunistic. His two campaign slogans, “America First” and “Make America Great Again,” each encapsulate that story while attacking those who he implies have betrayed the country and dragged it down.

The plain implication of “America First” is that our political leaders have not been putting the nation first. Although few may have recognized it, “America First” was the name and slogan of the leading isolationist group that before Pearl Harbor opposed going to war against European fascism and Japanese imperialism. Trump’s revival of the phrase was not unrelated to its original use. It highlighted his attack on internationalism, as in the television ad late in his campaign that denounced international bankers and displayed photos of Jewish financiers. “America First” also fit perfectly with his phony charges against the Clinton Foundation as a source of foreign influence when Clinton was secretary of state.

The genius of Trump’s attacks on globally oriented elites is that the 2016 election did include a candidate who owns a global business empire with financial interests abroad that pose unprecedented conflicts of interest in decisions about foreign policy—and that candidate, of course, was Trump. Moreover, Trump’s business is aimed precisely at catering to wealthy global elites. But by dressing himself up as the “America First” candidate, he telegraphed a message about national betrayal directly to people who believe that wealthy global elites have slighted them.

“Make America Great Again” appeals to the same belief that the leaders of the country have failed it and suggests that Trump, a winner himself, will bring that winning game to the nation. At a time when the president was black and a woman was running to succeed him, it hardly needed to be spelled out for Trump’s followers what was great about the past that needed to be restored. While Obama and Clinton symbolized an increasingly diverse America that was increasingly comfortable with its diversity, Trump embodied the discomfort with diversity among whites, particularly men. He artfully summoned up all the smoldering resentments of the Obama years—against blacks, against immigrants, against women, against the media, against “political correctness.” To all those unhappy with the changes since the 1960s, Trump presented himself as their way of taking back America—taking it back to an older, exclusive vision of who Americans are and must continue to be.

It’s tempting to say that there’s nothing new about these ideas. “America First” and “Make America Great Again” could have been slogans of nativist movements in the 19th and early 20th centuries. We have had a long line of racial and religious originalists who have insisted that America’s greatness stems from its white, Christian founding, rather than from the civic ideals of freedom and equality. The exact lines of conflicts between the forces of closure and those of openness have shifted, but the logic has been the same. When older-stock, native-born whites, typically more small-town and rural, see their power slipping away, they try to shut the gates and reclaim control. That was the impetus behind the immigration restrictions of the 1920s, which were designed to limit the entry of eastern and southern European Catholics and Jews. The same social and cultural forces also typically line up against internationalism and free trade.

Yet, as familiar as Trump’s narrative is, it was not the story about America that recent Republican presidents have told. Reagan was as sunny as Trump is dark. Even when using coded messages to appeal to whites, Reagan and the Bushes stayed within the norms of American politics, declining to incite hostilities, much less violence. The story they repeated was the exceptionalist, civic story of America as a city upon a hill, a beacon of freedom in the world. This is the vision sometimes called the American Creed.

Rhetorically, in fact, there is a more direct line from Reagan to Obama than from Reagan to Trump. Obama has sung the old exceptionalist saga, albeit in a liberal key. Here, for example, is Obama at his second inauguration:

…what binds this nation together is not the colors of our skin or the tenets of our faith or the origins of our names. What makes us exceptional—what makes us American—is our allegiance to an idea articulated in a declaration made more than two centuries ago: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal ….’

The patriots of 1776 did not fight to replace the tyranny of a king with the privileges of a few or the rule of a mob. They gave to us a republic, a government of, and by, and for the people, entrusting each generation to keep safe our founding creed.

Starting with this familiar invocation of “our founding creed,” Obama then takes the story in a progressive direction:

We do not believe that in this country freedom is reserved for the lucky, or happiness for the few. We recognize that no matter how responsibly we live our lives, any one of us at any time may face a job loss, or a sudden illness, or a home swept away in a terrible storm. The commitments we make to each other through Medicare and Medicaid and Social Security, these things do not sap our initiative, they strengthen us. They do not make us a nation of takers; they free us to take the risks that make this country great. …

It is now our generation’s task to carry on what those pioneers began. For our journey is not complete until our wives, our mothers and daughters can earn a living equal to their efforts. Our journey is not complete until our gay brothers and sisters are treated like anyone else under the law—for if we are truly created equal, then surely the love we commit to one another must be equal as well. Our journey is not complete until no citizen is forced to wait for hours to exercise the right to vote. Our journey is not complete until we find a better way to welcome the striving, hopeful immigrants who still see America as a land of opportunity—until bright young students and engineers are enlisted in our workforce rather than expelled from our country. …

Obama’s use of the American Creed to make the liberal argument infuriates conservatives. Christopher Scalia, the late Supreme Court justice’s son, writes that when Obama criticizes conservative positions by saying, “That’s not who we are,” he is accusing conservatives of being “un-American.” (Scalia cites a count by a conservative website that Obama has used the line “That’s not who we are” 46 times.) But Obama never questions conservatives’ patriotism or loyalty. When he says, “That’s not who we are,” he is saying, “That’s not who we are when we are at our best. That’s not who we should strive to be.”

Obama’s version of the optimistic, exceptionalist narrative has been a way for him not only to reappropriate it from Reagan, but also to speak for the nation, rather than as a “minority” leader. As a black politician, Obama has continually had to guard against the danger of being seen as representing blacks alone. The American story he has told, beginning with his speech at the 2004 Democratic Convention, has enabled him to lay claim to national leadership. Democrats will need to remember that lesson, especially as they confront the nationalism of the Trump presidency.

Will Trump Change Us?

We are now on the verge of one of the greatest U-turns in the history of national policy and politics. It may well change the basic workings of our government and private institutions and the role of the United States in the world. The impact is likely to be profound. Since government is a national looking glass, Americans will see themselves reflected in their government in an altogether different way from the Obama years. Many will look at that reflection and insist, “That’s not who we are.” But to the world—and to many Americans—that is who Americans will be, unless we organize and resist.

When a party controls all three branches of the federal government, it has the power to change society, not just policy. During the past 74 years, Republicans have controlled both Congress and the presidency for only six years (1953–1954, January–May 2001, and 2003–2006). Republicans now have their biggest opportunity since before the New Deal to consolidate a regime of their own making. Largely shorn of their moderate wing, they are a radical party with a radical president, eager to seize a rare moment to undo not only Obama’s legacy but many earlier achievements of Democrats going back three-quarters of a century—and to institute their own regime in ways that will be hard to reverse.

It is a peculiar fact of our political system, but a fact nonetheless, that a president’s loss of the popular vote has no effect whatsoever on his power. The fewer than 100,000 people in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Michigan who gave Trump an Electoral College majority have altered the course of American history—the only question is by how much. The 2016 election was literally a tipping-point election for the Supreme Court. Trump and the Republican Senate can immediately tip the majority back to the Court’s conservatives, and with additional seats likely to be filled, they will probably push the balance further to the right. With little to fear from the Court, Republicans can also pursue more vigorously the course they have already adopted through voter suppression and gerrymandering to make it difficult to vote them out of office. The power of incumbency in American politics is notorious. Since 2010, Republicans have used that power to consolidate their hold on state governments, and they are now poised to entrench themselves federally.

Many of the policies favored by Republicans for ideological reasons do double duty as means of political entrenchment. Policies weakening labor laws and unions strike at an organizational base of the Democratic Party. Deporting undocumented immigrants who have lived in America with their families for years, instead of providing them a path to citizenship, throws those communities into disarray. Privatizing government transfers not just functions but power and influence to private companies. Turning Medicare into a voucher and Medicaid into a block grant to the states eliminates the rights of beneficiaries under federal law and the role of federal agencies in upholding those rights. Defunding climate science at the Environmental Protection Agency and NASA defunds troublesome climate scientists.

Trump adds another element to the Republican potential for entrenchment. Immediately after the CEO of Boeing criticized Trump’s views on trade in early December, Trump tweeted that it was time to cancel the company’s contract to develop a new design for Air Force One. The message to corporate America was clear—that he would use all means at his disposal to punish any criticism. During the campaign, Trump threatened Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, owner of The Washington Post, with federal investigations because of the Post’s coverage. This is standard practice in populist governments, and not only with respect to the media. Through a combination of favors and threats, the regime turns business into an arm of the state. Republicans were supposed to prefer small government and oppose crony capitalism; they are bringing America the exact opposite.

If Trump does consolidate power in this way, it will have ramifying effects on American thought. Political leaders shape public knowledge and public opinion, even how people think about themselves. Never has more of a bully occupied the bully pulpit of the presidency. Americans identify with winners, and Trump has made winning the supreme good of his public philosophy. Winning governmental power does confer legitimacy as well as power. Those who win power can communicate their view of the world from a privileged, official position. When Trump was mainly known for birtherism, the media could treat him as a political crank. When he steps to the podium to speak as president, he must be accorded the respectful attention due the office. It is the greatest platform for grandiosity and falsehood the world offers.

From that position and the power that comes with it, Trump is going to affect who we are—but it may not turn out the way he intends. After assaulting the norms of American politics during the campaign, he seems a good bet to assault the norms of government and international relations as president. His bluster and recklessness will lead to crises, perhaps to war—and that is where the twin possibilities of Trump’s presidency may become clear. Populist leaders often look to crises as a means of enlarging their powers and suppressing dissent; war especially puts the opposition in the difficult position of appearing unpatriotic if it does not join in cheering on the troops. A people’s sense of their national identity may change in the process.

But crises are also the undoing of governments; leaders who take their countries to war often miscalculate their odds of a quick and easy victory. Crises may arouse a discouraged opposition and enable it to get back on its feet after being knocked down. When reversals of fortune come—whatever the occasion—the opposition must be ready with its own alternatives and its own story.

Remembering Who We Can Be

Trump and the Republicans now hold the upper hand. But an election in which Trump lost the popular vote by more than 2.7 million does not erase what Obama’s election disclosed about America. The United States is a divided society; many people may wonder whether it is even possible any longer to talk about “we Americans.” Trump’s America and Obama’s America may seem to be two entirely different countries. One and the same nation, however, made Obama its president twice and has now elected Trump, and our common reality is not one choice or the other but the contradiction between them.

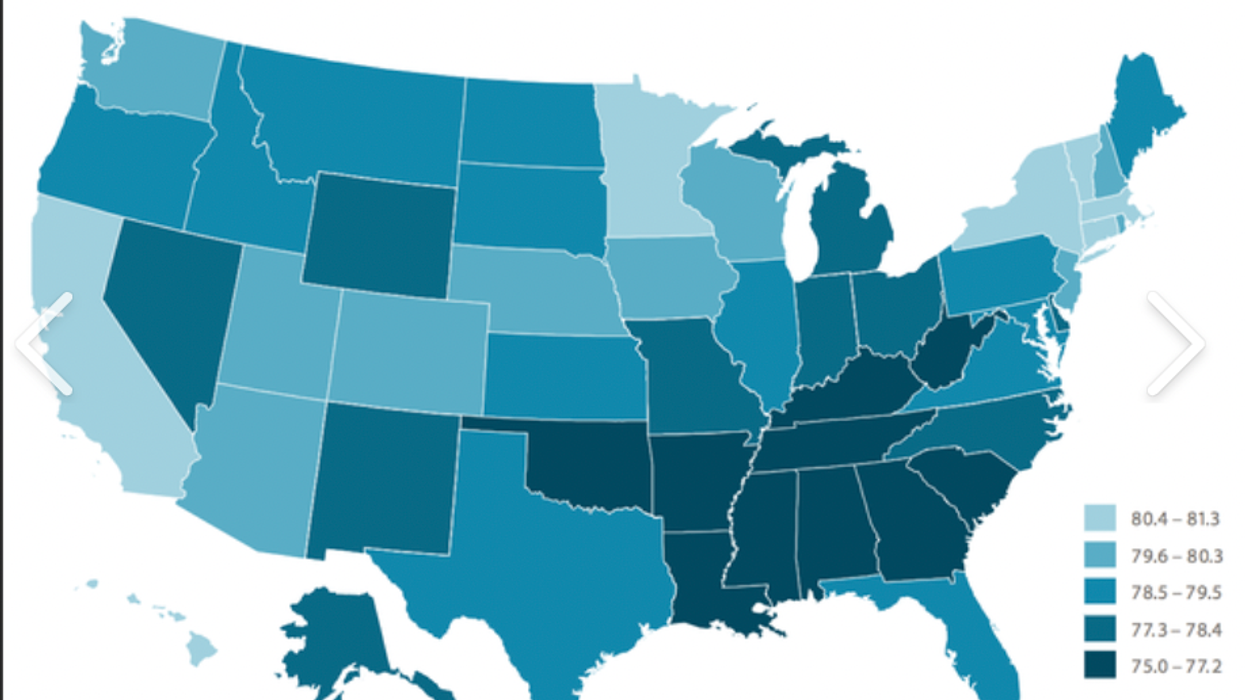

Nationally, Democrats have been winning majorities and losing elections. They have won the popular vote for president in six out of the past seven elections since 1992. But that support hasn’t been enough to win sustained power under the American political system. In the two elections in 2000 and 2016 that saw Democrats turn over the White House to Republicans, they have won the popular vote but lost the Electoral College. Clustered on the coasts and in cities, the Democratic vote has also been poorly distributed from the standpoint of controlling the House of Representatives, the Senate, or a majority of the states. The metropolitan clustering of Democratic votes undermines their ability to control the House and state legislatures, and in U.S. Senate elections, Democrats “waste” millions of votes running up big majorities in big states like California and New York. Democrats are now strongest in cities, the weakest part of the federal system.

The Electoral College, the structure of the Senate, and other aspects of the American constitutional system may be unfair, but they are not going to change anytime soon. If Democrats are going to regain power, they will have to broaden their support beyond the constituencies that now support them. They cannot expect salvation from demography even in the long run. Many progressives expect that “people of color” will become a majority and shift the balance of power. The very terminology is misleading. In the 2010 Census, 53 percent of Hispanics who chose one racial category identified themselves as “white” and when Hispanics intermarry with non-Hispanic whites (as 80 percent of Mexican Americans do by the third generation), the children overwhelmingly see themselves as non-Hispanic white. As a result of this pattern of “ethnic attrition” and the likely continued redefinition of who counts as white (and perhaps more important, who counts themselves as white), a majority-minority society will probably be a disappearing mirage.

Democrats have made a bet on being the party of diversity, and there is no going back on it. But they have a choice about how to frame their case. They can tell a story about the struggles of separate and distinct groups—racial minorities, immigrants, women, gays—a list that typically leaves out most white men. Or they can tell a story about America that brings whites in by honoring the country’s traditions as well as by emphasizing common economic and social interests. As Obama has shown, the national story can serve as the frame for contemporary struggles for equality. This is not exactly a rejection of “identity politics.” It is an identity politics of a kind—an effort to ground a majoritarian politics in a shared national identity.

The outcome of the 2016 presidential election wasn’t predetermined by demography, economic conditions, or other circumstances. Clinton might well have won the few additional votes she needed if not for intervention in the election by Russia and FBI Director James Comey. But Democrats still would not have won control of Congress or many of the states, and they will not be able to reverse the regime Trump and the Republicans put in place unless they can win that kind of widely distributed majority. Democrats can hone a much stronger economic message, and they should. They can hope that Republicans fall out and fight among themselves, which they may. But if we are to recover from the damage and national dishonor of Trump’s presidency, Democrats need to appeal to all Americans as Americans and help all of us remember how we can be genuinely proud of our country again.