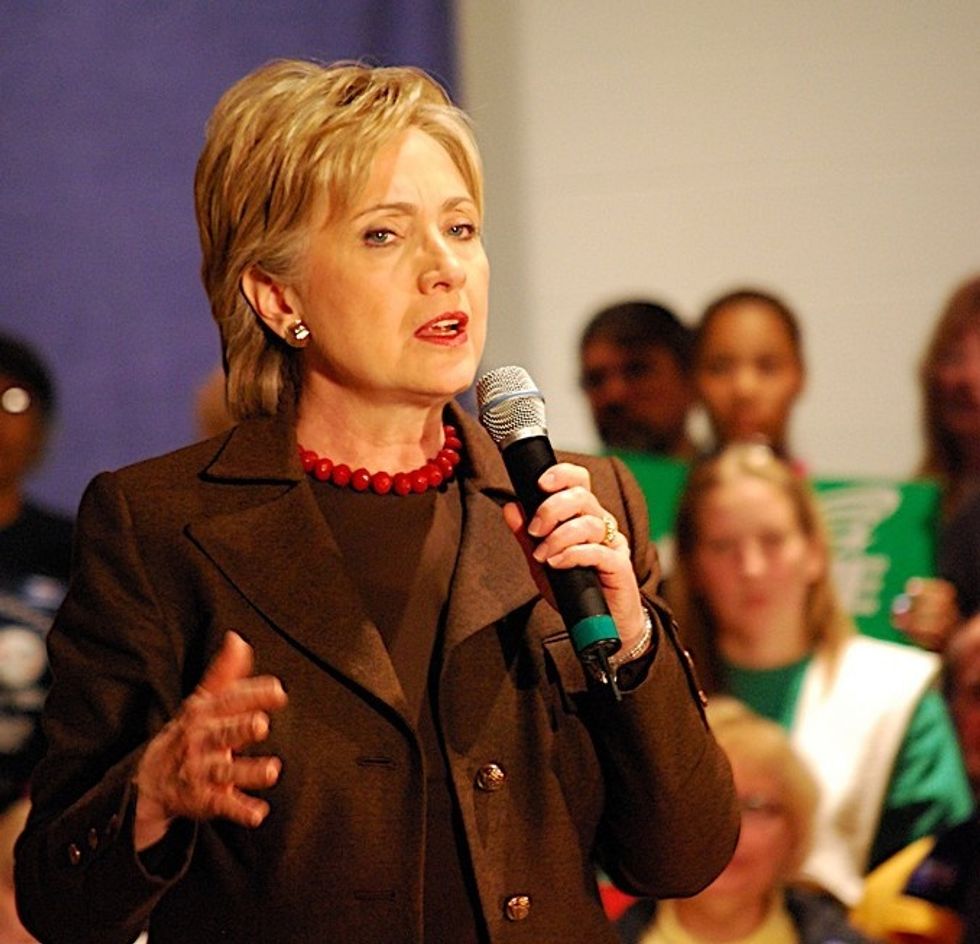

Sixteen Questions Hillary Clinton Should Answer

By Ramesh Ponnuru, Bloomberg News (TNS)

As her campaign for the presidency kicked off, Hillary Clinton managed to go 27 days without answering a question from the press. On Tuesday, she broke that streak. Here are a few questions reporters might want to ask the next time she decides to give her prospective subjects an opportunity to get unscripted answers from her.

1. President Barack Obama wants trade promotion authority, which would let him negotiate trade deals subject to an up-or-down vote from Congress. Should Congress give it to him?

2. Sen. Elizabeth Warren says that a future Republican president could use trade promotion authority to undo financial regulation. Obama says that’s nonsense. Who’s right in your view?

3. Do you believe that NAFTA — signed by your husband after the same expedited congressional review Obama wants _ has been on balance good for the U.S.?

4. Do you think that you were misled when you voted to authorize military force in Iraq in 2002? If so, by whom?

5. Given what we know now, were you right to oppose the surge of troops that President George W. Bush ordered into Iraq in 2007?

6. What in your view has the U.S. intervention in Libya achieved?

7. The New York Times reported last year that you “seemed flustered” and gave a “halting answer” when asked for your greatest accomplishment as secretary of state. You eventually said that “we really restored American leadership in the best sense.” Could you elaborate on what specific accomplishments you had?

8. What would you do about Islamic State as president? Do you agree with the Obama administration that it is “on the defensive throughout Iraq and Syria”?

9. Did you get advice from a lawyer about establishing and using a private email server as secretary of state? When you left the State Department, were you ever asked if you had returned all official records in your possession?

10. You’ve said that you would go further than Obama in shielding unauthorized immigrants from deportation if Congress doesn’t act. The Obama administration says that it has already done everything within its power. What legal steps do you think it has failed to take?

11. How much does the gender gap in wages reflect discrimination by employers, in your view, and how much does it reflect factors beyond employers’ control?

12. You’ve said that mental-health issues will be an important part of your campaign. Congressman Tim Murphy has a bill premised on the idea that existing government policy places too little emphasis on the most severe cases of mental illness and makes it too easy for those in the grip of such illnesses to refuse treatment. Do you agree?

13. Is there any point in a pregnancy after which abortion should no longer be available?

14. Obama said that he wanted a Federal Reserve chairman who would act to stop asset bubbles from “frothing up.” Do you agree?

15. Charity Navigator has put the Clinton Foundation on its “watchlist.” What do you make of that?

16. Does a candidate’s willingness to regularly answer questions from reporters tell us something about her attitude toward democracy?

That should do for an initial list of questions. On present trends, I suspect you’ll have plenty of time to come up with answers.

Ramesh Ponnuru is a Bloomberg View columnist. He may be contacted at rponnuru@bloomberg.net.

(c)2015 Bloomberg News, Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Photo: Alexander Wrege via Flickr