Carolyn Kizer, Pulitzer-Winning Poet, Dies At 89

By Steve Chawkins, Los Angeles Times

Carolyn Kizer, a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet whose sharp wit suffused even her most ardent calls for feminist progress and who declared in one of her best-known pieces, “I will speak about women of letters, for I’m in the racket,” has died. She was 89.

Kizer’s death Thursday at a nursing home in Sonoma, Calif., was caused by the effects of dementia, according to David Rigsbee, her literary executor.

One of Kizer’s poems was published in the New Yorker when she was 17. However, she never made it into the New Yorker again and started the serious study of poetry only as a newly divorced, 29-year-old mother of three.

“It was like a cork coming out of a champagne bottle, it was such a joy,” she told the Los Angeles Times in 2001.

Kizer received her Pulitzer in 1985 for her collection of poems called “Yin,” after the female principle in Chinese cosmology.

She also was a versatile translator, adept in Chinese, Urdu and other languages. At various times, she lived in China and Pakistan, where she taught writing under the auspices of the U.S. State Department.

As passionate about rewriting as she was about writing, Kizer could spend years polishing a single poem.

Her 1990 work, “Twelve O’Clock,” took about five years to complete, but spanned the universe. It recounted a smile that passed between the 17-year-old poet, who was visiting Princeton, and the aged professor Albert Einstein, who was ambling down a sunlit library aisle, “simple as a saint emerging from his cell.”

Reading books about physics for two years as she experimented with the poem, Kizer built her piece around the observer effect — the idea that observing a subatomic particle changes it.

“Equally, you cannot meet someone for a moment, or even cast eyes on someone in the street, without changing,” she told the Paris Review. “That is my subject.”

Other poems, like “Election Day, 1984,” were less lofty:

___

Did you ever see someone coldcock a blind nun?

Well, I did. Two helpful idiots

Steered her across the tarmac to her plane

And led her smack into the wing.

She deplaned with two black eyes and a crooked wimple,

Bruised proof that the distinction is not simple

Between ineptitude and evil.

___

One of Kizer’s most highly regarded works was “Pro Femina,” a four-part rallying cry for women poets.

In the 1920s, mawkish female poets were derided as the “Oh-God-the-Pain Girls” — a second-rate status that Kizer believed was encouraged by men. Decades later, in “Pro Femina,” Kizer recalled those days.

“Poetry wasn’t a craft but a sickly effluvium,” she wrote, “the air thick with incense, musk and emotional blackmail.”

In fact, she reminded her readers, women poets were “the custodians of the world’s best-kept secret: Merely the private lives of one-half of humanity.”

___

From Sappho to myself, consider the fate of women.

How unwomanly to discuss it! Like a noose or an albatross necktie

The clinical sobriquet hangs us: cod-piece coveters.

Never mind these epithets: I myself have collected some honeys.

___

Kizer later told an interviewer that some of her male colleagues thought “Pro Femina” was so bad she nearly threw it away.

Born in Spokane, Wash., on Dec. 10, 1924, Kizer was the only child of attorney Benjamin Kizer and his wife, Mabel Ashley Kizer. Her mother, who had a doctorate in biology, once astonished Kizer by turning down a job, asking, “Who would get your father’s breakfast?”

While Kizer grew up in privilege, her father was remote and domineering. When the subject of political parties came up at dinner, he was appalled when the precocious Carolyn told her parents’ guests, “Oh, we veer with the wind.”

“My father was livid,” she recalled in an essay. “I have suppressed what he said, but I know that I withered like a violet in an ice storm.”

She was 7 at the time.

Kizer went to Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, N.Y., where her music professors bluntly let her know she’d never be a concert pianist. Instead, she focused on literature and did graduate work in Chinese at Columbia University.

In 1946, she married Stimson Bullitt, a Seattle lawyer, and had three children with him before divorcing in 1954.

In 1955 and 1956, she studied poetry at the University of Washington under the renowned Theodore Roethke, a taskmaster who taught her, as she recalled in an introduction to one of his books, that “every line of a poem should be a poem.”

“I apply that to my own work and sometimes just throw up my hands,” she said.

Roethke was a merciless editor and Kizer used the same rigor with her students at the University of North Carolina and other schools.

“I made my speech to a class about passive constructions and a smart student said, ‘What about ‘to be or not to be?'” she once recalled. “I said, ‘Well that explains Hamlet’s nature: his ambivalence, his uncertainty — his basic passivity,’ and I got out of that one!”

From 1966 to 1970, Kizer was director of literary programs for the National Endowment for the Arts. She was a chancellor of the American Academy of Poets until 1998, when she resigned, with her friend Maxine Kumin, to protest the board’s lack of diversity at the time.

Kizer’s husband of 39 years, architect John Woodbridge, died in June. Her survivors include daughters Ashley Bullitt of Seattle and Jill Bullitt, of Hudson, N.Y.; son Fred Nemo of Portland, Ore.; stepchildren Larry Woodbridge of Brooklyn and Pamela Woodbridge of Berkeley, Calif.; six grandchildren; and three great-grandchildren.

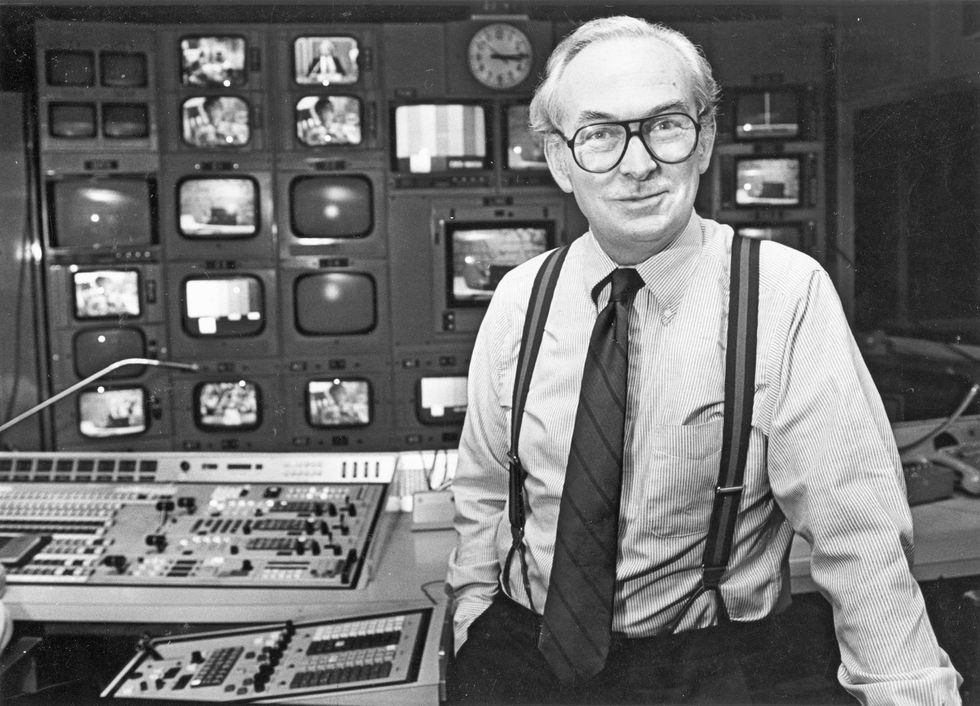

Photo via Los Angeles Times/John Todd

Want more national news? Sign up for our daily email newsletter!