Reprinted with permission from AlterNet.

Deedee Kirkwood is a hippie housewife in Camarillo, a scenic beach town in California outside of Los Angeles. When she was younger, she followed the Grateful Dead on tour and says she smoked copious amounts of pot “before and after.” But her youthful indiscretions had no legal consequences. “I did a lot of stupid stuff, but as a white lady I got lucky,” she tells me over the phone.

Kirkwood often writes letters to Fate Vincent Winslow, an inmate in the Louisiana State Penitentiary. He’s not as lucky as she was. In 2008, Winslow was homeless on the streets of Shreveport, Louisiana. One night, an undercover cop approached and asked him for “a girl” and some pot. Winslow got two dime bags of weed from a white dealer he knew and sold them to the officer. In all, he made five bucks from the sale, money he needed to buy food, he says.

Police arrested Winslow, but not the dealer, even though he’d profited more handsomely from the sale; the marked $20 bill was found on him.

During Winslow’s trial, prosecutors pointed to his long criminal history as a reason to put him away. But court records show he was far from a criminal mastermind. He had two nonviolent priors and a drug charge, which is not uncommon for poor people living on and off the streets. Still, after the predominantly white jury voted guilty, he was deemed a habitual offender. Under Louisiana law, that meant an automatic sentence of hard labor without benefit of parole, probation or suspension of sentence.

“I just keep praying I know everything will be all right,” Winslow writes in a letter.

“There are people serving life for marijuana,” Deedee Kirkwood says. “When I tell people about this, they don’t believe me.”

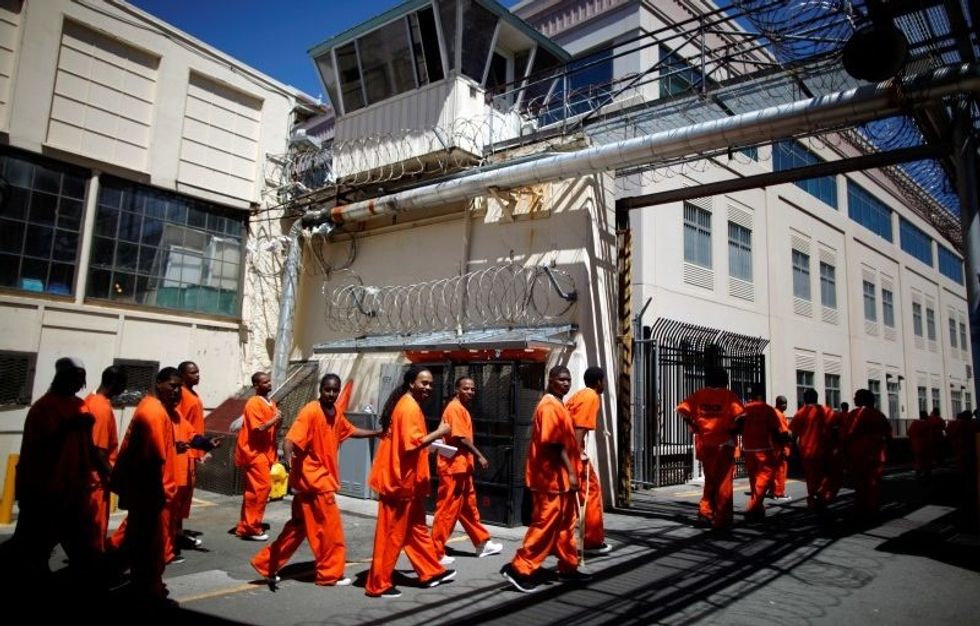

It does defy plausibility, even in the context of the American criminal justice system, which is hardly famous for being rational or sane. According to the ACLU’s “A Living Death” report, as of 2012, 3,278 people were serving life without parole for nonviolent crimes—and that’s just federally and in nine states. The states that have locked away the most people per capita are Louisiana, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Oklahoma.

Even at a time when more Americans support pot legalization—a Gallup poll released Wednesday found that 64 percent of Americans want legal weed—Fate Winslow is not the only person serving an absurdly long sentence for marijuana.

“Most people are shocked to hear that there are people serving a life sentence for pot, but there are many,” says Amy Povah, a former prisoner who now runs CAN-DO, an advocacy group for nonviolent drug offenders. Povah recalls doing a vigil outside of the White House for drug offenders serving long sentences. A passerby asked which country’s brutally oppressive regime she was protesting. He was surprised to learn she was there to draw attention to America’s prisons.

A slew of factors contributed to long sentences for drug crimes, but it mostly comes down to aggressive prosecutors and the legal tools lawmakers have given them in the past few decades. There are the mandatory minimum and habitual offender laws passed at the height of the crack panic in the 1980s and 1990s. Because of mandatory minimums, often well-meaning reforms end up empowering police and prosecutors in ways that target people of color and poor people at disproportionate rates. Take gun charges; aggressive prosecutors can stack up gun charges to inflate sentences for nonviolent drug crimes.

Michael Thompson got 40-60 years after selling a few pounds of weed to a police informant in a sting in 1994, in part because some guns were found in his house (two were antiques and one allegedly belonged to his wife). He’s still in prison in Michigan, despite lobbying on his behalf by his nephew Sheldon Neeley, a Democratic congressman in the Michigan house. “I’ve been here over 22 years over marijuana,” Thompson told me over the phone in disbelief. “Twenty. Two. Calendar. Years.”

During that time his mom died; he attended her funeral in chains. Her last wish was for her nephew the congressman to make sure her son didn’t die in prison.

Another reason someone might get a long sentence for marijuana crimes is through the use of conspiracy charges. That’s what happened to John Knock, a 70-year-old federal prisoner serving life without parole in New Jersey. His sister, Beth Curtis, who advocates on his behalf, explains how conspiracy charges can trigger an automatic LWOP sentence. “If you know anything about the 1960s…people didn’t go to prison for doing lots of things that they get buried for now,” she says. Her brother did take part in a marijuana smuggling operation, but by the time he was indicted, he was no longer involved in selling drugs. Yet, because of how conspiracy charges work, he was on the hook for all the drugs sold over the years by others involved in the operation. “Everything that was done by anybody during that time was attributed to him when he was indicted,” she says.

What Can Be Done?

Families Against Mandatory Minimums, CAN-DO Clemency and the Drug Policy Alliance are just a few of the groups and activists advocating for the release of prisoners serving long sentences. Civil liberties groups like the ACLU and Human Rights Watch have documented their plight for decades. Individual activists like Deedee Kirkwood write to prisoners like Fate Winslow because they can’t stand the injustice of people serving prison sentences for what she calls “a harmless plant.” Anything from dropping a few dollars into a prisoner’s commissary to writing letters to setting up with legal aid can help, as well as lobbying state governors to commute individual sentences while promoting more systemic reforms.

In the last year of the Obama administration, criminal justice reformers mobilized to lobby the Justice Department to grant as many commutations for nonviolent crimes as possible. Critics pointed out at the time that with the “law-and-order” Donald Trump about to get in the White House, the administration should have released more prisoners. At this point, their only chance is presidential clemency for federal prisoners, while people serving long sentences in state prisons can hope for a commutation from their governor.

Because both Republican and Democratic governors have to balance budgets, the call for criminal justice reform tends to be more bipartisan than most issues at the state level. But many states are starting from such an extreme point that even commutations or broader reforms end up relatively conservative. In one striking example, in 2017 Oklahoma Governor Mary Fallin changed the sentences of several drug offenders from life without parole to life with parole. One of them was William Dufries, who got caught with 67 pounds of marijuana in his RV after being pulled over because of a broken tail-light.

Most people who end up in jail over marijuana don’t get life. But even a short stint in jail that results in a record can mean years of financial and personal hardship. A 2016 report by the ACLU and Human Rights Watch found that marijuana arrests still outnumber arrests for violent crimes, entangling people in the criminal justice even for simple possession. In 2015, almost half of drug possession arrests were for weed (over 574,000), the study found. Even states with a thriving legal industry have failed to erase racial disparity in pot arrests; a 2016 NPR report found that minority teens were getting busted at even higher rates than before.

As support for legal weed continues to grow, what does the industry owe people serving time for marijuana? Tom Angell, a journalist and legalization advocate, points out that there’s a lot more drug advocates could be doing. “Even when we succeed in ending prohibition, our work isn’t done,” he writes in an email. He points out that the industry must look beyond legalization. “In addition to remaining forms of discrimination against cannabis consumers in the areas of employment, housing and child custody, there are still people serving time behind bars for things that are now legal.”

A few leaders in the weed community have advocated for criminal justice reform. Terra Tech CEO Derek Peterson has worked to get criminal justice reform language in legalization bills in New Jersey. San Francisco’s Nina Parks, who runs Mirage Medicinal, has spoken out about the need for reform; her own brother spent a year in Rikers after getting busted with weed in New York.

“We have to do our best to encourage policy that helps to heal the effects of targeting poor ethnic communities had on our culture,” she toldWomenofCannabiz.com. “While ensuring that there is a diverse and equitable industry and regulatory structure that really cares about public health and safety vs feeding a prison industrial complex.”

Despite Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ cranky antipathy against marijuana, a federal crackdown on the weed industry in states where it’s legal doesn’t seem imminent. Analysts who study pot markets have voiced concern that the threat of federal flexing on the issue might chill growth, if, for example, the prospect of more civic asset forfeiture actions spook business people or investors.

But overall, there’s not much evidence that a Sessions Justice Department has dampened enthusiasm for legalization. The Gallup survey released this week(referenced above) found that for the first time, even a majority of Republicans support marijuana legalization.

Even if the Sessions DoJ did shake up markets for a bit, that’s a far cry from dying in prison for a drug most college kids can get any night of the week by texting their weed delivery guy.

When I asked Fate Winslow in a letter how he felt about the fact that a drug that landed him in prison for life without the possibility of parole is now the basis of a million-dollar industry, he pointed to one obvious difference between legal pot entrepreneurs and himself.

“Those people have money,” he wrote.

Still, he’s surprisingly gracious that America seems to be evolving on marijuana, adding in his letter, “I don’t want no one else to have to go through this. I been locked up nine years for two $5 bags of weed that I didn’t even sell. I have life left to go.”

One of the biggest criticisms of life sentences is that they kill hope. If nothing you do can atone for your crimes, what’s the point of bettering yourself? Fate Winslow hasn’t given up yet. He’s taking classes. But it’s not easy for him to stay positive. He says he just keeps praying and tries to trust in god, even though he feels like god doesn’t care much about him.

When he writes Deedee Kirkwood, he asks about her grandchildren and compliments her family. He thanks her profusely for the card she sent, because it made him feel he wasn’t completely alone on his 51st birthday. He loves peanut butter, and the money she sent to his commissary allowed him to indulge in that rare treat for his birthday.

“I am still doing everything I can to get out of here,” he writes. “So keep praying for me.”

Tana Ganeva is a reporter covering criminal justice, drug policy and homelessness. Follow her on Twitter @TanaGaneva.