Tensions In Ferguson Have Been Simmering Below Surface For Decades

By Tim Logan and Molly Hennessy-Fiske, Los Angeles Times

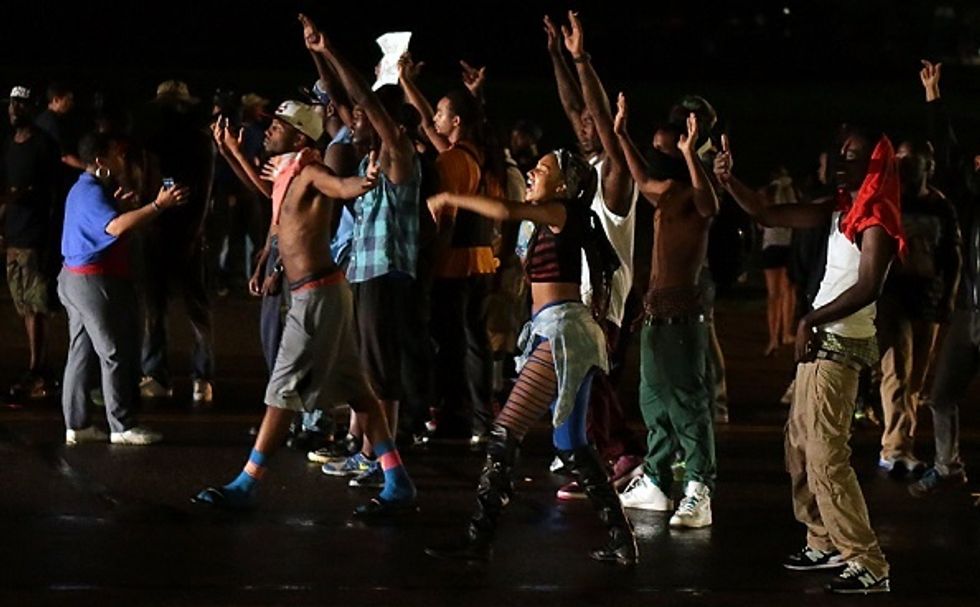

FERGUSON, Mo. — The police shooting of Michael Brown was the spark.

But the tinder fueling the anger and resentment that has exploded in Ferguson, Mo., has been building for decades.

The town has seen many middle-class homeowners who eagerly moved to St. Louis’ northern suburbs after World War II to buy brick ranch homes with nice yards leave, replaced by poorer newcomers. Good blue-collar jobs have grown scarce; the factories that once sprouted here have closed shop. Schools have struggled.

And local governments — slow to evolve — often now look little like the people they represent. For the black community, it creates a sense of lost opportunity in a place much like other aging suburbs in the Rust Belt and across the country.

“For a young black man, there’s not much employment, not a lot of opportunity,” said Todd Swanstrom, a professor of public policy at the University of Missouri, St. Louis. “It’s kind of a tinder box.”

The seething tensions prompted Missouri Gov. Jay Nixon to declare a curfew in Ferguson on Saturday, one week after a white police officer shot and killed Brown, an 18-year-old black man. The declaration followed another night of looting.

Critics say an initial heavy-handed response by police using tear gas and rubber bullets touched off the unrest, with mainly white officers facing off against mainly black crowds.

Since Brown’s death, race and police tactics have dominated the headlines blaring from this town 12 miles northwest of St. Louis’ Gateway Arch. But that’s only part of the story.

From jobs to schools to racial transition, Ferguson and its neighboring towns — where many protesters came from — have undergone sweeping changes in recent years. Some places have become pockets of poverty, comparable to the poorest spots in St. Louis.

Others, like Ferguson, remain more mixed, with middle-class subdivisions alongside run-down streets and big apartment complexes like the one where Brown lived. Either way, Swanstrom said, the area highlights the growing challenge of the “suburbanization” of poverty.

“This was a catalyst for something much deeper, the lack of economic opportunities and representation people have,” said Etefia Umana, an educator and board member of a community group called Better Family Life. “A lot of the issues are boiling up.”

It’s been boiling for decades.

St. Louis’ jumble of suburbs — there are 91 municipalities in a county of about 1 million people ringing the city — has long been sharply segregated. Until the late 1940s, restrictive covenants blocked blacks from buying homes in many of them.

Well into the 1970s, tight zoning restrictions and other rules, especially in places near the city’s mostly black north side, kept many largely white, said Colin Gordon, a University of Iowa professor who’s studied housing in St. Louis.

That began to change by the 1980s, when middle- and working-class white families began leaving north county — as the area around Ferguson is known — for newer, roomier housing further out in the exurbs. In their place came a flood of black families from St. Louis in search of better housing and schools.

“When black flight out of the city began, this was the logical frontier,” Gordon said. “It became what the city had been, a zone of racial transition.”

In Ferguson, the change happened fast. In a generation — from 1990 to today — the population changed from three-fourths white to two-thirds black. Even as the area’s demographics shifted, good blue-collar jobs sustained many of these towns, said Lara Granich, a community organizer.

“Everyone in our parish was a brick layer or a letter carrier or something. I didn’t know anyone who had gone to college, but they all made a decent living,” said Granich, who grew up in nearby Glasgow Village, another neighborhood on the decline. “The people who live there now tend to work at McDonald’s.”

The recession hurt, too. This part of the St. Louis region took the brunt of the foreclosure crisis, with subprime loans turning bad, and investors scooping up cheap houses to rent. Auto plants that had sustained a black middle-class shut down.

Since 2000, the median household income in Ferguson has fallen by 30 percent when adjusted for inflation, to about $36,000. In the Census tract where Brown lived, median income is less than $27,000. Just half of the adults work.

Fr. Steven Lawler, rector of St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church in Ferguson, really saw the change in 2008, when visits to his food pantry spiked. They haven’t gone down since.

“I know there are places where an economic recovery’s happening,” he said. “But in the places where people are most stressed, there hasn’t been a recovery.”

Still, as Lawler and others note, Ferguson has some things going for it. Its pleasant, old downtown has seen a revival in recent years, with a busy Saturday farmers market and a new craft brewery. It still has middle-class neighborhoods of historic homes. The headquarters of a Fortune 500 company — Emerson Electric Co. — sits on a serene campus just up the hill from the gas station looters burned a week ago Sunday night.

Gail Babcock, program director at Ferguson Youth Initiative, was quick to note her town still has a strong sense of community — and every morning last week volunteers have poured in to clean up from protests and looting. The challenge is in connecting its poorer residents — especially younger ones — to it.

“It’s very hard for them to find jobs,” said Babcock, who runs a community service program for youth convicted of minor criminal offenses. “That sets up a situation where they tend to get in trouble, and they probably wouldn’t under other circumstances.”

Then there are the schools, one reason why many families moved to these suburbs in the first place. Two north county districts — including the one where Brown graduated from high school in May — have lost their state accreditation in recent years. The district Ferguson shares with a neighboring town remain accredited but scores low on state tests.

That was a big reason why John Weaver took the morning off work Friday, drove his plumbing truck to Florissant, and asked the visiting Gov. Nixon what he planned to do about the problems that have plagued these neighborhoods for years.

Nixon acknowledged there’s “a lot of work to do.” Weaver was not impressed.

“All these politicians say they’ll fight for our education. I feel cheated,” he said in an interview later. “And if I feel cheated, how should these kids feel?”

These issues are all tied together for Shermale Humphrey, a 21-year-old who joined the protests last week. She plans to enlist in the Air Force, but right now works at a McDonald’s near where Brown was shot. She’s something of a veteran activist — helping to organize strikes by fast-food workers in St. Louis — and sees race and local politics and economics here as closely intertwined.

“It’s a shortage of everything,” she said. “It’s a shortage of jobs. Of African Americans on the police force and in government. Of people not being able to get a good education.”

Adding to the frustration, many protesters say, is that the people still running many of these downs don’t much look like the people who live there now. Just three of Ferguson’s 53 police officers are black. Six of seven City Council members are white. So are six of the seven school board members, who run a district with a student body that’s 78 percent black.

Many of these towns are still run “like little fiefdoms,” said Umana, who moved to Ferguson eight years ago, by remnants of their old white middle class that may not share the concerns of newcomers.

“The numbers flip-flopped, but the power structure remained the same,” he said.

It has been hard to build black political leadership in these fast-changing suburbs, said Mike Jones, a black veteran of St. Louis’ political scene. Indeed, it’s been harder than in St. Louis, which has long been racially mixed.

But a more diverse set of voices at Ferguson City Hall, Jones said, might have avoided the heavy-handed police response that only inflamed protests.

“The question is how — in a city that’s 67 percent African-American — do you have absolutely no African American political representation?” Jones asked. “That’s what leads you to a police force that could become involved in this sort of incident.”

It’s an issue more communities will have to face, Jones predicts, as traditionally “urban” issues of poverty and racial change migrate to suburbs often less-equipped to deal with them. And not just in St. Louis.

A study last month by the Brookings Institution found the number of poor people living in high-poverty suburban neighborhoods nationwide more than doubled in the last decade, growing much faster than in big cities.

Chris Krehmeyer, who runs St. Louis-based community development nonprofit Beyond Housing, says he knows colleagues around the country dealing with a lot of the same issues as he is in north St. Louis County, tackling housing and jobs and schools all at once. The key, he said, is to build trust with residents before the community blows up.

Ferguson is a bellwether, he said. “This story could happen in lots of different places, all over this country.”

Photo: Robert Cohen/St. Louis Post-Dispatch/MCT