Ukraine Isn't One Big War -- It's A Hundred Little Wars

The way the war in Ukraine is covered in the news makes it seem like a singular thing – the attack Russia launched against its neighbor country eight months ago that is still ongoing. We get reports of missile and drone strikes on cities like Kyiv and Kharkiv; the same kinds of strikes on power plants and other crucial infrastructure; movement of Ukrainian forces near Kherson; the big offensive when Ukraine took back nearly 3,500 square miles of its territory in the northeast which had been lost in the early weeks of the war.

No war is a single thing, a gigantic battle that one side wins and the other loses, or even a series of a few major battles, even if, as has happened so far in Ukraine, the two sides fight each other for nearly a year.

I make this mistake myself all the time. Recently, I wrote a column that said British defense officials believe that Russia has suffered 90,000 casualties since the war began. That is a terrible figure, and it does reflect serious damage to the Russian war effort, but it is not of much use in describing what is going on over there. Each casualty on either side, Ukraine or Russia, is an individual tragedy for the family that loses a soldier who has died or been seriously wounded, even crippled for life. It's a loss to the unit in which the soldier serves. It doesn’t take heavy losses in a unit for morale to flag, for the unit’s discipline and cohesion to be damaged enough to render it ineffective as a fighting unit.

This happens because the guys who get killed or wounded are the friends of the soldiers who survive. The survivors are damaged by the loss of their buddies. They can begin to lose confidence in their leaders if they come to blame the loss of their friends on incompetence by platoon leaders or company commanders or higher commanders like colonels and generals.

It's almost unknowably hard for a unit to lose soldiers in combat. I’ll give you one rather small example from the time I spent with the 101st Airborne Division in Iraq in 2003. I was embedded, as it was said, with a company that held a small base camp in downtown Mosul. The day I arrived, a two-vehicle convoy had been hit by machine gun fire, killing a sergeant major and his driver, who was a private first class from the company I was with. It was just two soldiers, but you could feel the strange mix of depression and anger in the air that accompanies such a loss. The sergeant major was popular with everyone in the battalion. The PFC from our company was a kid from Illinois who was fond of practical jokes and was really good at the video games the troops played during their downtime. Everybody liked him. There was a box containing his personal effects in the hallway just outside the company command center. Within hours of his death, soldiers had already left notes and cards that would be sent with the man’s effects back to his family in the States.

That night, two of the company’s platoons were dispatched on a patrol to either kill or take prisoner the insurgents responsible for the attack. They had been located in a neighborhood on the south side of Mosul some distance from the company’s basecamp in town. One platoon was given the task of approaching the house where the killers were thought to be hiding. The platoon I was with was held in reserve a short distance away in case fighting broke out that the other platoon couldn’t handle by itself.

I was astounded when the compound where we were held in reserve turned out to be occupied by another company in a different battalion. Their basecamp was literally just down the street from where the insurgents were hiding, and yet they were not dispatched to bring them in or kill them. Two platoons from the company of one of the men who were killed were sent.

It was obviously a revenge mission. The guys who lost their friend wanted to get the Iraqis who killed him. The mission succeeded without a fight. Three Iraqi insurgents were taken prisoner and driven to the brigade base camp where they would be held. When we returned to the barracks late that night, the soldiers were jubilant.

That’s just one little story about a loss suffered in combat in another war nearly 20 years ago, but it is illustrative of how the bigger war we caused by invading Iraq was really a series of little wars fought by units as small as a platoon of 25 or 30 men against an enemy that consisted in this case of three insurgents. The company in the 101st had nothing to show for their victory except the satisfaction of bringing the killers to some sort of justice. No land was taken and occupied. There was no retreat by enemy forces. No surrender was offered or taken.

The situation in Ukraine is different, because they are fighting to retake land that was theirs to begin with, land that is now occupied by an invading army. The front lines in the war stretch from the border with Russia in the north to the Black Sea in the south. Because it’s not a straight line, it is at least several hundred miles long. There is fighting along nearly its entire distance. That means a company of Ukrainian soldiers and their artillery may be fighting in a section along the Dnipro River in the south less than five miles from where a platoon is holding territory it took from Russians a few days ago. And so on.

It’s nearly impossible for commanders to keep track of it all. When I was in Iraq, I attended multiple BUP’s, or Battle Update Briefings, of different sizes: I attended one in the division headquarters outside of Mosul when General Petraeus sat in front of three flat screen televisions as brigade and battalion commanders reported the situation in their areas. Behind Petraeus was a kind of bleachers, where staff officers sat with laptop computers linked to the screens showing their reports on supplies, operations, intelligence, casualties, unit locations and movements. It was an impressive aggregation of a whole lot of very complicated information. Similar BUP’s were held daily at brigade, battalion, and company levels throughout the division. It’s the way the various commanders kept up with what was going on in their units of varying sizes and their areas of operations.

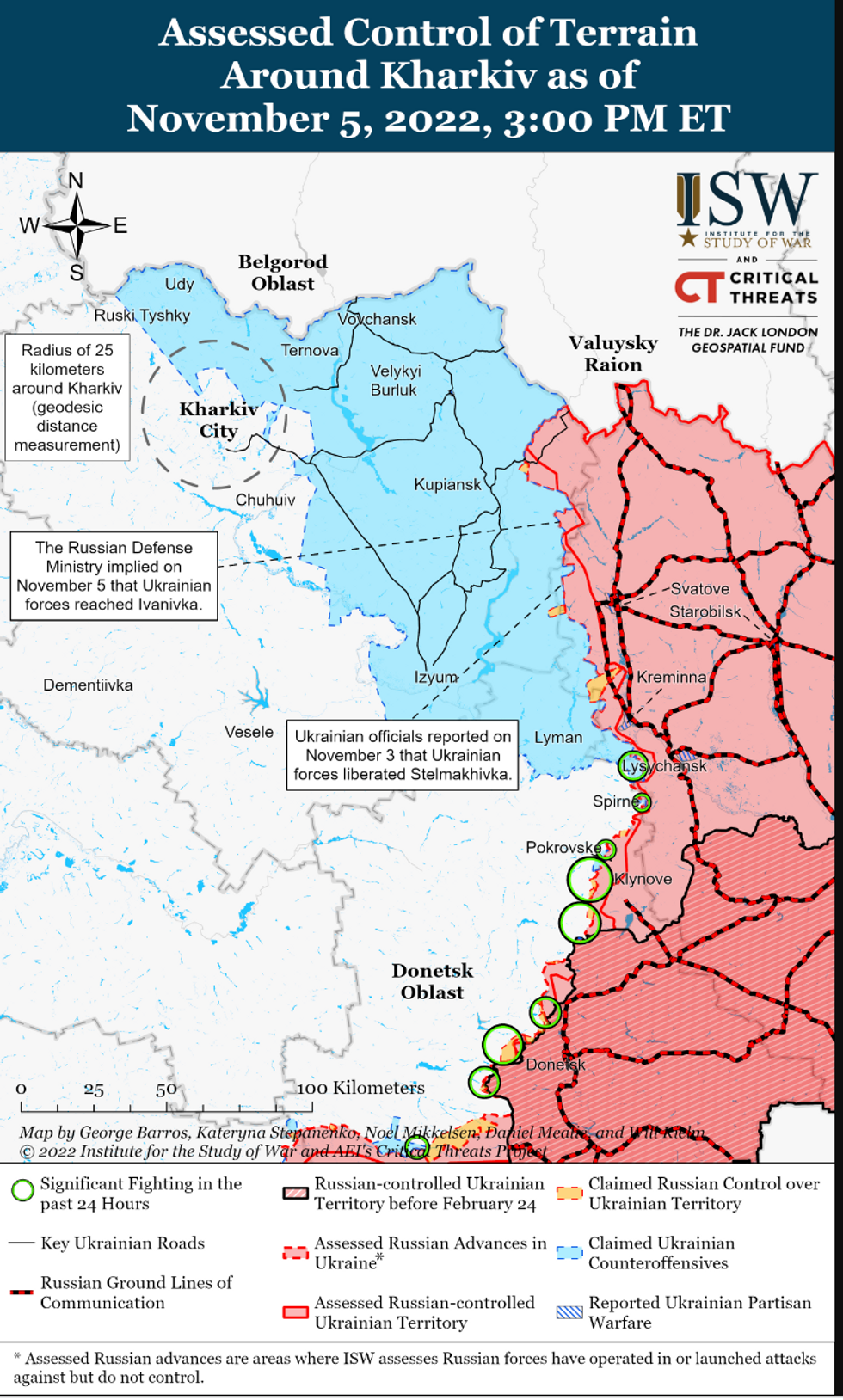

To give you an idea of what’s going on in Ukraine in just one section of the front, the Kharkiv and Luhansk regions, I’ll turn to a report filed yesterday by the Institute for the Study of War (ISW), the Washington think-tank which has been excellent in the way it has followed the war. Here is the text of the report; the bracketed numbers indicate the source for the information in the report, when available:

Russian sources claimed that Ukrainian troops continued counteroffensive actions along the Svatove-Kreminna line on November 5. Russian sources, including the Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD), reported that Ukrainian troops conducted an assault in the direction of Kuzemivka, 13km northwest of Svatove.[16] A Russian milblogger claimed that Ukrainian troops crossed the Zherebets River west of Svatove and are probing Russian positions along the Kuzemivka-Kolomyichykha line.[17] Geolocated footage shows Ukrainian troops conducting strikes on Russian armored vehicles about 30km northwest of Svatove, indicating that Russian troops maintain positions in the Yahidne-Orlianka area.[18] A Russian milblogger claimed that Ukrainian forces are regrouping in this area after a failed assault on Yahidne.[19] A Russian milblogger reported that Ukrainian troops continued attempted attacks towards Kreminna.[20] The Ukrainian General Staff reported that Ukrainian troops repelled a Russian attack on Bilohorivka, 10km south of Kreminna.[21] Russian sources also claimed that Ukrainian forces conducted a HIMARS strike on Russian positions in Svatove and Kreminna and shelled Russian positions along the Svatove-Kreminna line.[22]

That report contains information about at least seven separate actions along a front that is approximately 250 km, or 150 miles long. You can see in the individual pieces of information that some of the reported attacks or artillery strikes are within 30 miles of one another. The Svatove-Kreminna line, for example, is about 15 miles long, according to the map below. One of the reports says a Russian attack 10 km or six miles south of Kreminna was repelled by Ukrainian troops. It’s unknown how large the Russian or Ukrainian forces were, but they could have been as large as a battalion of 250 men or as small as a platoon of 25. Here is a map of that region, showing areas of recent combat circles in green and black:

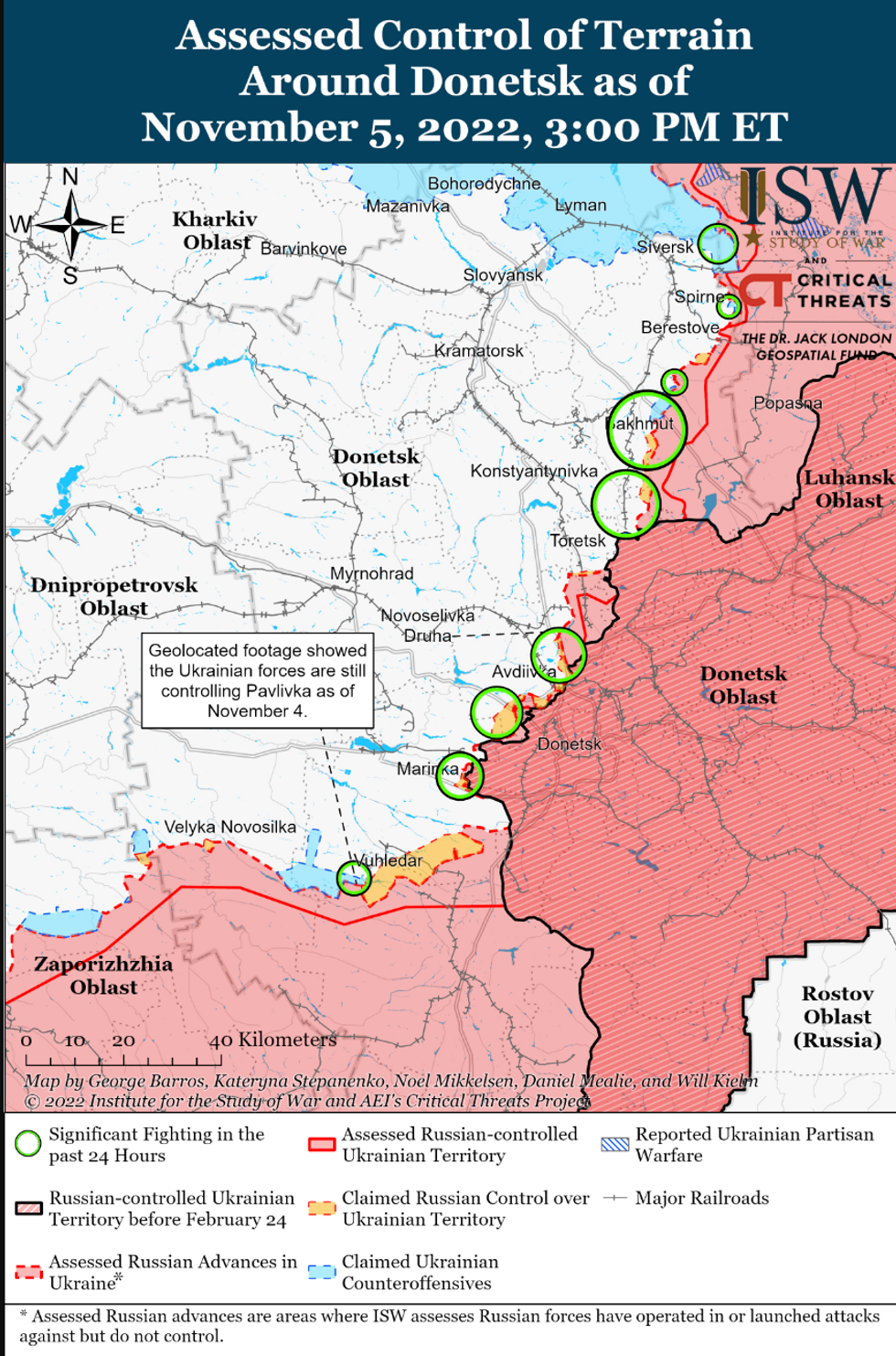

Another report by ISW about the front lines around Kherson described no less than five major actions along a front of about 80 km, or 48 miles. A third report about the Donetsk region described nine separate incidents of combat along a border about 250 km, or 150 miles long. The combat included Russian attempts to cut off a highway, separate attacks on two villages south of Bakhmut, a center of intense fighting over the past week, and Ukrainian counterattacks around five villages surrounding Bakhmut in preparation for an attempt to take the town itself. Here is a map of the region showing recent areas of combat circled in green and black:

A more general report by ISW described Russian artillery, drone and missile strikes on nine separate cities in Ukraine, with Ukrainian air defenses shooting down at least eight Russian drones.

All of this happened on one day.

It would be inaccurate to say some wars are not as intense as the war in Ukraine. The wars that have been reported on in Africa, the battles still raging in Syria, the internecine battles in Iraq – they’re all like this.

Every war in this way is war only more so – a greater hell on earth comprised of a lot of little hells on earth, with civilians perishing along with soldiers. All of them die from bullets, from fragments of artillery rounds and rockets, from explosions caused by drones and missiles, and by war crimes committed one by one, sometimes in multiples.

We can only hope that such hell is not visited upon us and that all we have to do is read about it and see photographs of the destruction and sometimes the dead. It’s a fragile hope, but it’s all we’ve got.

- Russians Who Fled Putin's Draft Now Stranded In South Korean Airport - National Memo ›

- In Ukraine War, 'Escalation' Is Just Another Deadly Lie - National Memo ›