Published with permission from the Washington Spectator.

A friend of mine, the ace political journalist Tom Zoellner, writes of last week’s vice-presidential debate, “So Pence lies like a bad carpet and he’s proclaimed ‘the winner’ because he said it in a smooth way and avoided important questions?” Which, as we bate our breath for Sunday’s “town hall” tilt between Clinton and Trump, raises a puzzle wrapped in a riddle wrapped in an enigma: how did an institution meant to elevate presidential campaigns end up making them even stupider than before?

The history of the modern presidential debate goes back to 1948, when New York Governor Thomas Dewey and Minnesota Governor Harold Stassen, contending for the Republican nomination, faced off in a radio studio over the question, “Shall the Communist Party be outlawed?” Stassen argued the affirmative, while Red-baiting Dewey about the number of Communists in New York. Dewey came back with the memorable line, “You can’t shoot an idea with a gun.”

Dewey’s anti-demagogic response—and the fact that Dewey won the nomination—suggested a promising precedent. Adlai Stevenson had been thoroughly dismayed with his experience running for president in 1952, especially by his opponent General Eisenhower’s television commercials, which Stevenson’s advisers hoped he would make, too. “The presidency is not a box of cornflakes,” high-minded Adlai responded. (His governor’s mansion in Springfield only had one TV, which was usually on the blink; when he wanted to catch a ball game he went to a friend’s house). Running again in 1956, he found himself disgusted by the specter of electioneering via “the jingle, the spot announcement, and the animated cartoon”—not to mention the endless recitation of the same ghost-written speech, which made no sense to him in the era of coast-to-coast network TV. He wanted to propose a series of televised joint discussions. His advisers talked him out of it, lest Adlai come off in debate against genial old Ike like the pompous egghead elitist of popular legend. (An apocryphal story has it that a woman yelled out to him at a campaign rally, “Governor Stevenson, you have the vote of every thinking American!” He answered, frowning, “Yes, but I need a majority.”)

The egghead returned to the idea in a magazine article in 1959: why not “transform our circus-atmosphere of presidential campaigning into a great debate conducted in full view of all the people?” Why not “a discussion on the great issues of our time with the whole country watching”?

“And we can decide them not after canned rhetoric and TV spectaculars but only after intelligent discussion which the candidate and the networks can provide.”

Intelligent discussion: why not indeed? First, because the TV networks had no interest in providing it. Newton Minow, Adlai Stevenson’s law partner, who went on to become the chairman of President Kennedy’s Federal Communications Commission, tells the story in his coauthored 2008 book Inside the Presidential Debates: Their Improbable Past and Promising Future. He recounts that the networks didn’t want to give away the air time.

At hearings held by Senator John Pastore’s Commerce Subcommittee on Communications, Governor Stevenson implored, “The television stations are licenses of the public, they enjoy monopolies, granted by the public of great value, they already have an obligation to provide public service programs, to broadcast in the public interest.” To argue against the idea, the networks wheeled out 84-year-old Herbert Hoover—who as Calvin Coolidge’s Secretary of Commerce had helped write the 1927 Radio Act—to argue that compelling free air time was “government censorship of free speech.” Broadcasting magazine said it violated the Fifth Amendment (“. . . nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation”). And a witness from the National Association of Broadcasters called it “favoritism by the federal government in providing free platforms as between candidates of major and minor parties.”

They had a point, one that federal law already recognized. Section 315 of the 1934 Federal Communications Act mandated, out of simple fairness, that “if any licensee shall permit any person who is a legally qualified candidate for any public office to use a broadcasting station, he shall provide equal opportunities for all other such candidates for that office.” Which presented a sticky problem for Pastore’s subcommittee if they wanted to pave the way for a televised presidential debate in 1960: upwards of a hundred candidates ran for president every four years. What to do about a fellow like Lar Daly, the Chicago eccentric who campaigned in an Uncle Sam suit? Talk about a “circus atmosphere”!

Of course, they did manage to overcome it. Here’s how: Congress voted a temporary suspension of Section 315 for the 1960 presidential election. What happened next, of course, made history: the “Great Debates” between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon, celebrated forevermore as a high-water mark in the history of American electioneering. InThe Making of the President 1960 Theodore White called it a “revolution . . . born of the ceaseless American genius in technology,” a “simultaneous gathering of all the tribes of America to ponder their choice between two chieftains in the largest political convocation in the history of man.”Huzzah!

So if 1960 was so great, why didn’t it happen again until 1976? Because of Lyndon Johnson, that old son of a gun. He had no interest in elevating the stature of that buffoon Barry Goldwater by appearing with him side by side on stage. It was hardly an afternoon’s work for him to lean on Pastore’s subcommittee to smother any possible cancellation of Section 315 for 1964 in its cradle. It provided a precedent: incumbent Richard Nixon and semi-incumbent Hubert Humphrey, in 1972 and 1968, had no trouble working the same trick, public interest be damned.

Minow and his coauthor Craig L. LaMay narrate the next chapter of the saga with relish. Keen legal minds figured out a loophole: if a third party staged the debates, not the networks or the campaigns themselves, the networks could cover them—could not but cover them—under a 1959 decision that suspended the equal-time mandate when it came to coverage of “bona fide news events,” which the first face-to-face presidential debate would indubitably be.

The League of Women Voters stepped up as the third party. They drafted Newt Minow to co-chair the proceedings. He rang up another former FCC chair, Dean Burch, then working for the Ford campaign, to ask if they were willing. They were. Yes, Ford was the incumbent; but following the Democratic convention, Jimmy Carter was way, way ahead. “Newt,” Burch explained, “when you’re 32 points behind, what else are you going to do?”

And then, remarkably, Carter’s ensign responded to the same invitation: “We know we are 32 points ahead in the polls, but Jimmy doesn’t think the country knows him.”

The debate was on. But for that miraculous concord, who knows whether there ever would have been another one again.

I wrote about what happened next in my last piece here at the Spectator: the goofy technical glitch that saw both candidates standing stock still for 27 minutes, live on the air. Why that happened helps explain why presidential debates became less than great. The conventional wisdom was that you couldn’t win a debate, only lose one, so the best tactic is to prepare within an inch of your life and risk nothing. The results are hilariously recounted in a wild and unjustifiably obscure campaign chronicle by a charismatic old D.C. fixture named Victor Gold, who is still with us. Considerable effort was expended in the Carter camp on how Carter should address his adversary. (“Mr. Ford,” they decided: neither too deferential nor too disrespectful.) Mr. Ford practiced for a week in an exact mockup of the set, with—an innovation to be repeated—figures like Alan Greenspan and Brent Scowcroft standing in behind Carter’s podium in practice sessions, recorded it with the cameras set at the show’s precise angles so Ford’s TV adviser could better instruct the Leader of the Free World precisely which postures—literal postures—it would be best to assume.

Then, as the real-life stand-ins were not sufficient, the debate-prep team devised the following loopy workaround: a TV set was perched on what would be Carter’s lectern, which played Carter’s answers on shows like Meet the Press,which Ford would respond back to in turn.

Carter endured a painstaking regimen of his own. Between the first and second debates he was apparently conditioned to look at the camera more and smile. Four communications researchers at the State University of New York in Buffalo, The New York Times reported, “attempted to quantify what they described as an ‘analysis of 4,458 specific nonverbal behaviors and 628 verbal references’ in the first and second debates. After 500 hours of work on the subject, they have now reported that Mr. Carter looked at the camera 85 percent of the time in the second debate compared to only 26 percent in the first,” and amped his smileage totals to “95 slight smiles in the second debate and 14 broad ones.” This compared to 42 and four respectively for the guy who kept charge of the nuclear codes. This was plainly not the political revolution Teddy White had in mind.

What the TV debates have given us instead is a revolution in impression management. By 2004, a 22-page memo of understanding between the John Kerry and George W. Bush campaign stipulated what names the candidate would address each other by, what they and the moderators were or were not allowed to say (“. . . In each instance where a candidate exceeds the permitted time for comment, the moderators shall interrupt and remind both the candidate and the audience of the expiration of the time limit and call upon such candidate to observe the strict time limits which have been agreed upon herein by stating, ‘I’m sorry . . . [Senator Kerry or President Bush as the case may be]. . . your time is up’ . . .”). And also, for the vice-presidential debate, that the “Commission shall construct the table according to the style and specifications proposed by the Commission.”

Another precedent was introduced in these 1976 proceedings. Ford, supposedly, made a doozy of a blunder when he said “There is no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe . . .” The subject, actually, was complicated (you’ll have to wait for my next book for the details about why, or can read about it here or here). Basically Ford was restating settled U.S. foreign policy. He was also, with daring nuance, saying precisely the sort of thing these debates were supposed to be introducing into presidential electioneering. Early soundings showed that viewers thought their president had done just fine. The media, however, seized upon the out-of-context and nuanced quote, insisting it proved Ford was a feckless buffoon, convincing voters to believe them and not their lying minds.

Thus did the revolution of Teddy White’s dreams also become a revolution in nit-picking impression-control by the media, an obsessive patrolling for “gaffes” that guaranteed the debates would become progressively less open and less edifying.

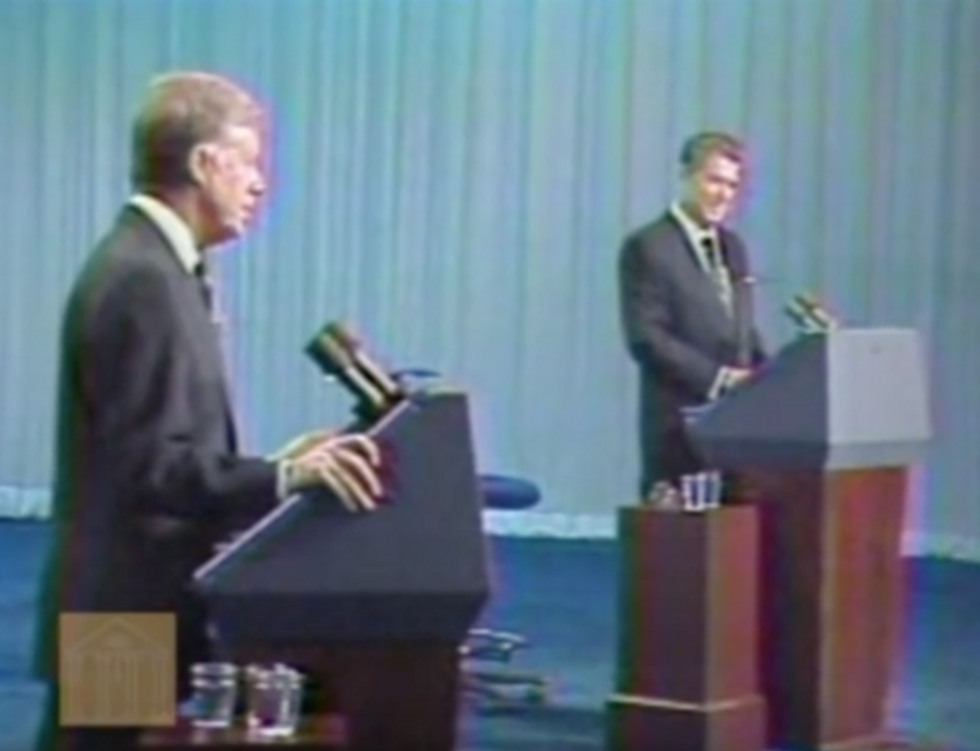

Gaffes, and “zingers” were Ronald Reagan’s unique contribution to the devolution of the presidential debate. A Carter speechwriter once told me that the White House was absolutely confident that if they could only get the boss onstage with the doddering old actor then Carter’s superior intelligence and technical mastery would be obvious, and he would run away with the election. Not only did they misjudge their opponent, they misjudged the medium, which by then seemed almost purpose-built to favor the candidate who was better with the snappy quip.

In 1980 it was “Are you better off now than you were four years ago?” Not a bad question, and a fair one. In 1984, however, Reagan hit a grand slam off 62-year-old Walter Mondale, when asked by the moderator whether he had any doubt that he could go with very little sleep for days on end, as John F. Kennedy did during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Reagan responded: “Not at all, Mr. Trewhitt. And I want you to know that also I will not make age an issue of this campaign. I am not going to exploit, for political purposes, my opponent’s youth and inexperience.”

That put to bed the issue that Reagan was then almost 72 years old, and that many believed he already was suffering the early symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. Because he made everyone laugh, even Mondale.

Adlai Stevenson rolls over in his grave. Insert your own absurdity here: Michael Dukakis neglecting to lustily assert his desire to rip his wife’s hypothetical murderer’s heart out through his chest; Al Gore sighing wrong. Whatever. The egghead from Illinois had somehow midwifed a political medium that ended up as American politics’ quintessential vehicle for glib numbskullery, the very essence of Aristophanes’s parody of rhetoric as the art of making “the weaker argument prevail over the stronger.” Just ask Tim Kaine.

Rick Perlstein is The Washington Spectator’s national correspondent. His books include Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus and Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America.

Photo: Carter-Reagan debate, October 1980.

Trump Cabinet Nominee Withdraws Over (Sane) January 6 Comments