After the ratification of the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments to the U.S. Constitution — abolishing enslavement, awarding citizenship to Black Americans and guaranteeing their right to vote (Black men, anyway) — it was a time of progress and celebration.

African Americans were elevated to positions in cities, states and at the federal level, including American heroes such as Robert Smalls of South Carolina, first elected in 1874, who served in the U.S. House of Representatives. He was well known by then, though. His sailing skills were crucial in a dramatic escape from enslavement that saw him hijack a Confederate ship he would turn over to the U.S. Navy.

But not everyone viewed the success of Smalls and so many like him as triumphs, proof of the “all men are created equal” doctrine in the Declaration of Independence. For some whites, steeped in the tangled myth of white supremacy and superiority and shocked by the rise of those they considered beneath them, the only answer was repression and violence, often meted out at polling places and the ballot box.

It didn’t matter that these newly elected legislators, when given power, promoted policies that benefited everyone, such as universal public schooling.

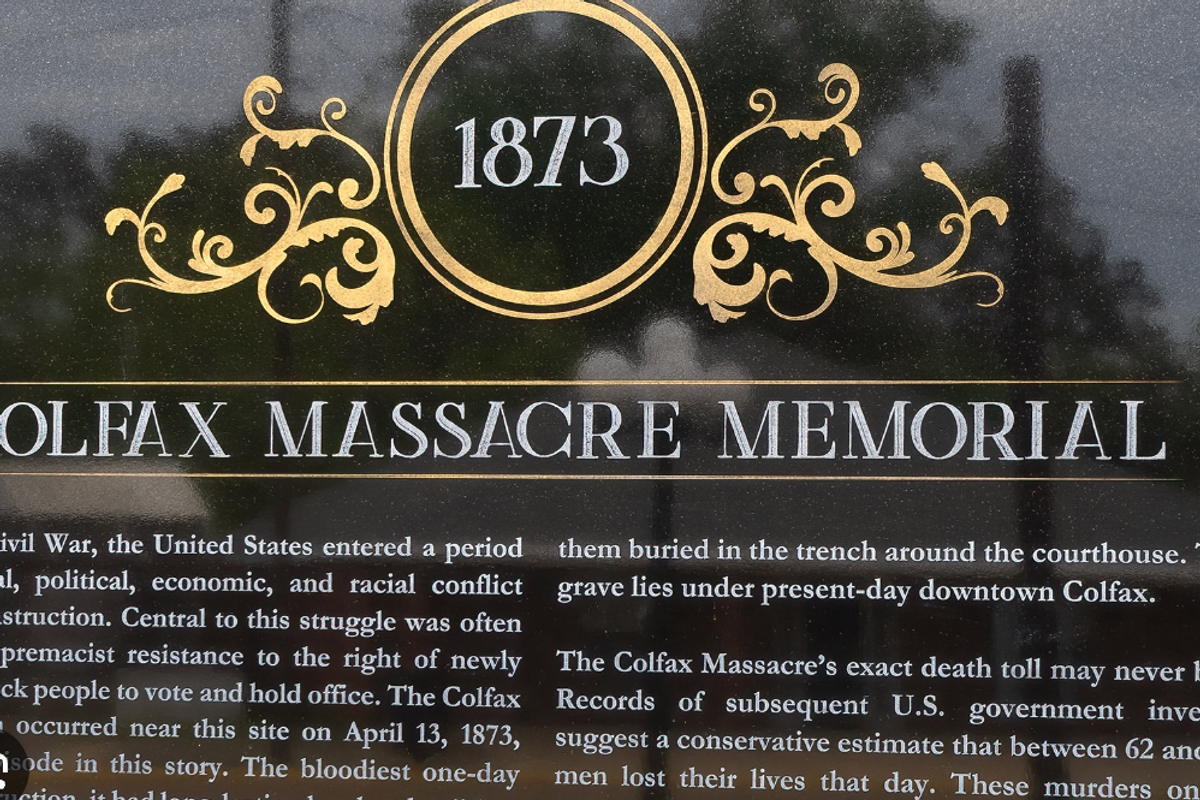

In incidents throughout the South, the White League and the Klan killed Black men who had the audacity to exercise their right to vote, intimidating and silencing those who considered doing the same. In the Colfax Massacre in April 1873, an armed group set fire to the Colfax, Louisiana, courthouse, where Republicans and freed people had gathered; between 70 and 150 African Americans were killed by gunfire or in the flames. In Wilmington, North Carolina., white vigilantes intimidated Black voters at the polls, and in 1898, in a bloody coup, overthrew the duly elected, biracial “Fusion” government.

Reconstruction gave way to “Redemption,” couching a return to white domination in the pious language of religion, not the first or last time God was used so shamelessly as cover.

The perpetrators then were Democrats, allied against Lincoln’s Republican Party.

Today, it’s most often Republicans — afraid they can’t convince a majority with ideas alone — who engage in tactics to shrink the electorate to one more amenable to a “Make America Great Again” promise, one that harks back to a time that was not so great for everyone.

It’s not a coincidence that those most amenable to the leader of that movement are white Christian nationalists, eager to align a flawed messenger with a higher power, in order to gain more power on earth.

But the tools are subtle in 2024.

In Republican-led states, with like-minded legislatures, a proliferation of laws has erected hurdles to voting, ones that opponents say disproportionately hit minorities, the poor and the elderly. This week, a federal court in North Carolina is hearing a case brought by the NAACP that is fighting voter ID requirements that Republicans in the state say are not tough enough.

Donald Trump and the Republican National Committee have announced an effort to recruit 100,000 poll watchers in battleground states. You don’t have to be a mind reader to imagine where they could be stationed — Philadelphia, Atlanta, Detroit, Milwaukee — the places where minority voters are concentrated and where Trump insists fraud is going on.

From the 1980s until a few years ago, the RNC was hampered by a consent decree after complaints that posting armed, off-duty law enforcement officers at polls in minority neighborhoods just might intimidate voters. You have to wonder if they’ve learned anything.

America has seen it all before.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968, laws that simply sought to balance the scales, right wrongs and achieve some semblance of justice, were all greeted with pushback that the government was going too far, too fast — that whites were losing something when minorities gained long-denied rights.

Some in the crowd in America’s 21st-century attempted coup, on Jan, 6, 2021, toted Confederate flags and signs demanding a violent take back of a country they don’t recognize and don’t want to accept.

Trump in Time magazine echoes the grievances that have never faded away, as he lays out his plans if elected in November. He promises policies to address what he calls a “definite anti-white feeling” in America.

“If you look at the Biden administration, they’re sort of against anybody depending on certain views,” Trump told Time. “They’re against Catholics. They’re against a lot of different people. … I think there is a definite anti-white feeling in this country and that can’t be allowed either.”

No proof, of course, that Mass-attending President Joe Biden is anti-Catholic, or that African Americans, with disproportionate outcomes on everything from maternal health to housing, are cruising along. But division and victimhood are all Trump knows. He supports his followers’ views, all FBI evidence to the contrary, that discrimination and hate crimes against whites are bigger problems than discrimination and violence against African Americans.

Trump and Republicans have already succeeded in states across the country, outlawing the teaching of basic history like the facts at the top of this column, for fear the truth about hard-fought gains, often accompanied by bloody sacrifice, might hurt someone’s feelings or perhaps provoke empathy and understanding for the “other.”

Ignorance of history makes it much easier to sell the lie that the 2020 election was stolen and that byzantine rules and poll watchers are needed to prevent the same in 2024.

Trump’s antics in a Manhattan courtroom have drawn all the attention, understandable with headlines about adult film stars, tabloids and the like. Trump won, in part, in 2016 because he knew how to suck up all the oxygen in the room.

But it’s important to pay attention to the words and actions of those who only love an America that excludes rather than includes the voices and votes of all its citizens, those who look back and like the view.

We’ve seen that America — throughout history and as recently as January 2021. It wasn’t pretty.

Reprinted with permission from Roll Call.