You Have The Right To Vote -- Maybe Even If You're In Jail

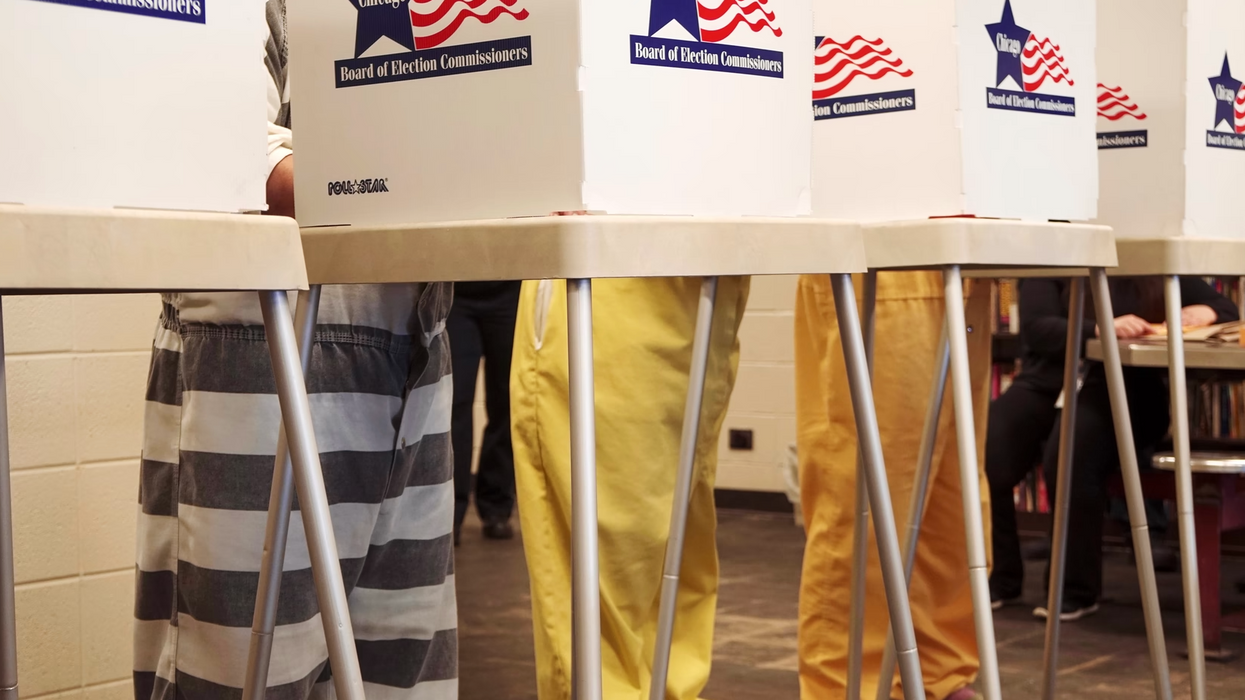

Prisoners voting in Cook County Jail

They’ve been eligible to vote since 1974. That year, in the case of O’Brien v. Skinner, the Supreme Court of the United States held that “misdemeanants” or accused people who haven’t been convicted of felonies are eligible to vote just as they would be were they not in custody.

Casting a ballot from jail is nice work if you can get it. The ballot that is.

In theory, about 547,000 incarcerated people should be voting on November 8. Most have to vote through an absentee ballot just like they would if they were out of town on Election Day.

But ballots are hard to come by, and usually for specious reasons. A witness at the October 10, 2019 hearing on Washington DC’s Restore the Vote Amendment Act — the first law in the country to actually re-enfranchise incarcerated people since the two states that allow prisoners to vote never took away their rights in the first place — described situations where prison mailrooms failed to deliver the absentee ballots to the inmates. Even if they get the ballot in their hands, inmates have to pay for the postage to return it. Commissary purchases can take as long as two weeks in some places; stamped envelopes aren’t guaranteed.

Of course, barriers start well before the distribution of ballots. In Houston, Texas, Harris County Sheriff Eddie Gonzalez recognized that his jail confiscates the photo ID needed to register and vote.

The same was true in the city and county of Denver, Colorado. It frustrated the voting of the detainees so broadly that the county changed its voter registration rules to allow photocopies of licenses and photo ID’s rather than requiring detainees to have them in hand, as they’re technically contraband.

The solution to these problems was to turn jails into actual polling stations — and that’s exactly what seven jails have done, according to the advocacy and research nonprofit Prison Policy Initiative. Now those seven facilities — the jail in Washington D.C., two in Illinois, including Cook County Jail, one in Los Angeles, two in Colorado, and Harris County Jail in Houston, Texas — will act as polling places on Election Day. That basic right to vote and the logistics to implement it are coming together

But the challenge of getting pretrial detainees to vote goes beyond coordinating how it's done. Ward Six Councilman Charles Allen of the District of Columbia City Council, who chairs its committee on the judiciary and public safety, wondered whether formal civics education was necessary to get detainees to vote; he even speculated whether that would include having a dedicated member of the city's board of elections stationed at the jail.

According to Allen, 73 unsentenced people voted in the primary at the D.C. jail and 127 in the general election in 2018. Those numbers amount to about one percent of the average daily population when it was at its lowest.

To be fair to Washington, the District may be the hardest place in the country to implement detainee voting. Inmates in the city may not be in the facility long enough to vote; the average length of stay for men is 136 days and 70 days for women.

After that, if a sentence is imposed, the federal government ships them out of the city to federal prisons across the country, in states with different laws. About 3700 people — two thirds of incarcerated D.C. residents — vote from somewhere else. That distance requires that they receive a traditional absentee ballot to mail in.

But the results aren’t that great in other jurisdictions. While about 40 percent of Cook County Jail detainees voted in the 2020 presidential election, the exceptional circumstances of that year — reduced inmate populations because of the pandemic and four separate days of early voting over two weekends — enhanced participation.

During the June 2022 primary, only 25 percent of detainees voted, even though same day registration should have made it easier for many more to participate in the democratic process. It was still a higher turnout rate than for citizens at large — and it’s up from seven percent in 2018 — but jail voting participation rates should top 85 percent when the facility becomes a polling place with on-site registration.There’s no concern about transportation, not making it in time, or even competing obligations. Turnout is solely the responsibility of the constituents.

And that’s what proves that it’s not convenience of voting that brings about participation; it’s knowledge of the right. And most incarcerated people don’t know about their rights, even when the voting booth gets installed in the lobby of their building.

An advocate with Speak Up and Vote in Illinois said those detained in jail frequently “didn’t realize they’re eligible to vote, so they didn’t try”-- as did someone working with the Denver Sheriff’s Department, who said that detainees “told us this was their first time voting and they had no idea they had the right the vote.” Harris County Sheriff Gonzalez essentially conceded the “majority of people involved in the justice system don’t vote due to a lack of information on voting.”

The task of turnout is educating people on rights they’ve always had but either didn’t know or didn’t care about.

No matter what the participation level is, putting voting booths inside jails is a bold move. We think of the laboratories of democracy as sterile places, crucibles that cook up only the purest policies. To let detainees and their voluntary behavior — ballot casting isn’t required — teach corrections administrators how to implement these rights takes a lot of trust.

It’s especially brave since granting voting rights for prisoners isn’t a favored political move. James Carville, political consultant and former lead strategist for the Clinton campaign in 1992, complains about it a lot, but his essentially bigoted stance isn’t totally out of touch. A HuffPost//YouGov poll surveyed a group of 1000 US citizens and found that 63 percent favored voting rights for people when they complete their sentences. That support then plummets by more than half, to 24 percent, when the topic of re-enfranchising prisoners comes up.

The opposition to voting rights for incarcerated people is outdated, for sure; our nation’s highest court has allowed unconvicted detainees to vote for almost 50 years. That we’re just figuring out how to let them do that in 2022 is both heartwarming and disheartening at the same time.

Chandra Bozelko did time in a maximum-security facility in Connecticut. While inside she became the first incarcerated person with a regular byline in a publication outside of the facility. Her “Prison Diaries" column ran in The New Haven Independent, and she later established a blog under the same name that earned several professional awards. Her columns now appear regularly in The National Memo.