After years of whispers and anticipation, former senator and Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton is embarking on her second run for the White House—and it’s going to be a long and contentious road to the Democratic convention and Election Day. Her supporters and detractors alike are girding for an interminable run of stories on Benghazi and private emails, Monica, and perhaps even Whitewater. No attack will be deemed too nasty; every rumor and accusation, no matter how specious, is always fair game — because the Clintons remain perennial targets of a scandal-starved media and a Republican machine hellbent on her defeat.

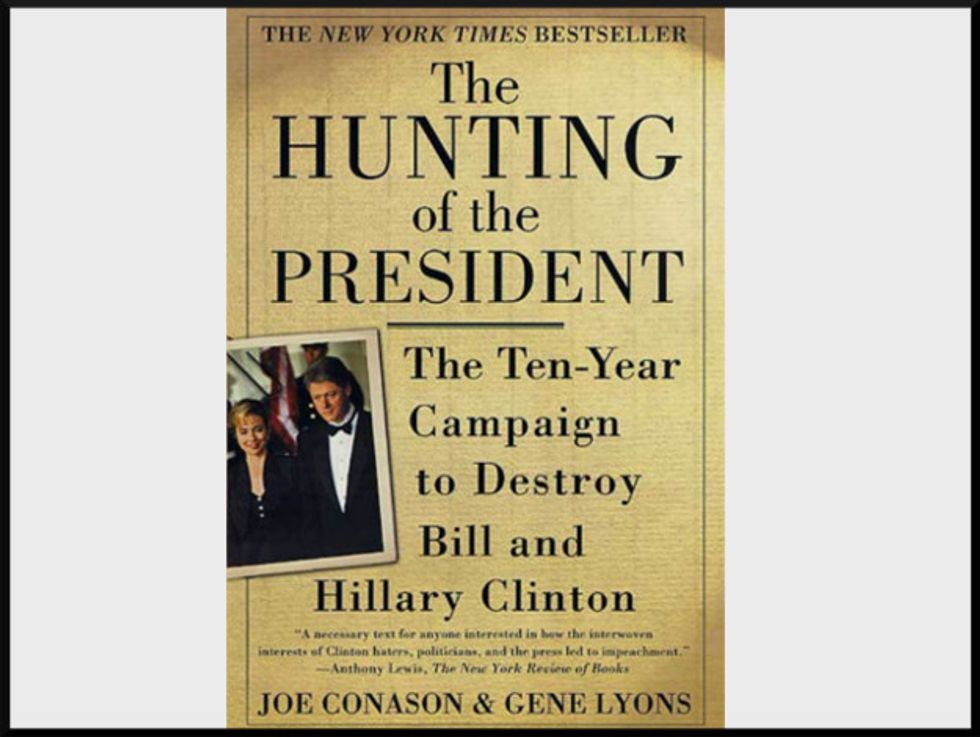

Fifteen years after its publication, The Hunting of the President: The Ten-Year Campaign to Destroy Bill and Hillary Clinton, by Gene Lyons and National Memo editor-in-chief Joe Conason, still rings with relevance. The crosshairs may have shifted toward Hillary in the last decade or so, but the offensive is still very much engaged and demands a response.

Within months after Bill Clinton’s first inauguration, the Washington press corps and the right-wing media began a sustained campaign of scandal-mongering against the president and his wife, the new First Lady. The slanderous rumors ranged from corrupt real-estate deals and bank fraud to drug smuggling and multiple homicides. None of it was true, yet all of it was swept up into a bizarre, paranoid, hour-long videotape called The Clinton Chronicles, starring a fired Arkansas state employee and former radio jingle writer named Larry Nichols—and distributed nationwide by none other than the Reverend Jerry Falwell.

You can purchase the book here.

With President Clinton’s popularity edging toward record lows during the spring and summer of 1994, The Clinton Chronicles videotape became an underground sensation. Citizens for Honest Government would later claim sales of more than 150,000, with perhaps double that number of bootleg copies in circulation. The religious right’s Council for National Policy bulk-ordered copies for all its members, and Matrisciana sent tapes to all 435 members of Congress and to influential Washington journalists.

Indiana Republican Rep. Dan Burton—a Foster conspiracy buff who achieved a degree of notoriety by conducting an amateur ballistics test in his backyard involving a .38 revolver and a watermelon—invited Clinton Chronicles star and narrator Larry Nichols to Washington and introduced him to like-minded House members. Evangelical churches, particularly across the South, showed the video during services. Conservative talk radio amplified its ominous message to an audience of millions.

Eventually, the president was forced to defend himself. He gave an interview to the Minneapolis Star-Tribune on April 8, 1994, complaining about the right-wing media. “There’s something that those of us who are Democrats have to contend with. The radical right has their own set of press organs. They make their own news and then try to force it into the mainstream media. We don’t have anything like that. We don’t have a Washington Times, or a Christian Broadcasting Network, or a Rush Limbaugh, any of that stuff.”

Interviewed in June on KMOX, a St. Louis radio station, Clinton complained again about the “constant, unremitting drumbeat of negativism.” A KMOX reporter asked Clinton if he was referring to the Reverend Jerry Falwell and The Clinton Chronicles. “Absolutely,” he said. “Look at who he’s talking to. I mean, does he make full disclosure to the American people of the backgrounds of the people that he has interviewed that have made these scurrilous and false charges against me? Of course not.”

Falwell responded by inviting the president to prove his innocence. He told the New York Times that Clinton should be angry not at him but at those who made the accusations. If Clinton were to “tape a personal and direct rebuttal” to the video indictment, the reverend promised to broadcast it unedited on The Old-Time Gospel Hour. Floyd Brown, author of Slick Willie, and previous employer of the talents of fired state employee and Clinton fabulist Larry Nichols, and old-time racist diehard Justice Jim Johnson, who also starred in the video, said the Clintons were very “thin-skinned.”

The president’s complaints caused a flurry of front-page stories in newspapers like the New York Times and the Philadelphia Inquirer that inevitably focused on the more sensational accusations and observed that the videos offered no proof that Clinton was a drug-smuggling murderer. These articles provoked an oddly defensive editorial in the Wall Street Journal on July 20, 1994. While conceding that many of The Clinton Chronicles accusations made no sense, the Journal editors still insisted that “the Falwell tape and the controversy around it get at something important about the swirl of Arkansas rumors and the dilemma it presents a press that tries to be responsible. The ‘murder’ accusation, for example, is not made by Mr. Falwell or Mr. Nichols, but by Gary Parks, whose father was gunned down gangland style on a parkway near Little Rock last September.”

The elder Parks had run a private security firm that supplied guards outside Clinton’s Little Rock headquarters during the 1992 campaign. The anti-Clinton clique, including the London Sunday Telegraph‘s Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, deduced that he had been killed because he knew too much about Clinton’s sex life. The Journal acknowledged that there was no evidence, and speculated that “Jerry Parks had plenty of reason to have enemies, and his family may be overwrought.” That was how Little Rock police viewed the still unsolved crime. (Gary Parks eventually apologized for accusing Clinton and expressed regret about his involvement with the video.)

The Journal editors also stipulated that they could not “for a minute imagine Bill Clinton knowingly involved, even tangentially, in plots of violence.” Yet even in criticizing Falwell, they published the names of several more putative Clinton “victims” previously listed in the British press. Then, chafing against the niggling constraints of responsible journalism, they went further.

Rumors about Clinton were “old news to any of the journalists covering Arkansas scandals, but few of us have shared any of this knowledge with readers…. Finding no real evidence of a Clinton connection, and feeling that the President of the United States is entitled to a presumption of innocence, we decline, in the name of responsibility, to print what we’ve heard. And then it is left to less responsible sources to publish the first reports, and the disclosure of basic facts adds credibility to their sensational interpretation, especially among those losing trust in the mainstream press.”

The performance of the mainstream press did leave much to be desired as far as knowledgeable Arkansans were concerned. Highly influential articles about the president and his home state continued to appear in prominent publications with information that was scarcely more accurate, if less luridly presented, than the Clinton Chronicles. Taken together, they strengthened the Washington press elite’s impressions of Bill and Hillary Clinton’s scandal-ridden past.

The Journal first betrayed its own impatience with journalistic restraint during a farcical episode that had occurred earlier in 1994. That incident, too, involved Larry Nichols, along with a writer named L. J. Davis. At issue was a cover story that ran in the April 4, 1994, issue of The New Republic – edited at the time by a young, right-wing import from Britain named Andrew Sullivan. Headlined “The Name of Rose,” it purported to be an expose of Arkansas’s “colorful folkways”and corrupt political culture. With the venerable Washington magazine’s imprimatur, Davis introduced the worldview of The Clinton Chronicles to an influential, sophisticated elite that would scoff at the Falwell videos.

The Davis article, which had been rejected by Harper’s magazine, sketched Arkansas state government as a “Third World” criminal conspiracy among Bill and Hillary Clinton, the Rose Law Firm, and Stephens, Inc. Assisted by “sinister Pakistanis” and “shadowy Indonesians,” this cabal had looted the president’s home state and now menaced the nation.

Considering that Larry Nichols and a Republican political consultant named Darrell Glascock were the writer’s two primary sources, it was unsurprising that he erred so badly. (Some months after the Davis article appeared, Glascock copped a plea in a scam involving a fraudulent state purchase of 50,000 nonexistent U.S. flags, and gave testimony that sent his co-conspirator to jail for 17 years.)

Employing no fact checkers at the time, the New Republic was helpless against Nichols and Glascock’s inventions. Two examples should suffice: “With the stroke of a pen and without visible second thought,” Davis wrote, “then-Governor Clinton . . . gave life to two pieces of legislation inspired by his wife’s boss [i.e., the Rose Law Firm]—revising the usury laws and permitting the formation of new bank holding companies.” Supposedly by abolishing the constitutional 10 percent limit on interest rates, Clinton had enriched Stephens, Inc., which owned Worthen Bank, then the state’s largest. In return, Worthen had hired Hillary’s law firm as its outside counsel, in exchange for which Clinton had made it “a major depository of the state’s tax receipts.” Next, Worthen had given the Clinton presidential campaign a $3.5 million line of credit, and so on—much the same tale told in The Clinton Chronicles.

In reality, the usury law was changed not by Bill Clinton, but by a constitutional amendment enacted in the 1982 general election. It was placed on the ballot by the legislature, at the urging of Republican governor Frank White, a banker, and became law before Clinton became governor. Furthermore, Stephens, Inc., didn’t own Worthen Bank either when the amendment was enacted or when Davis’s article was written 12 years later. The Rose Law Firm had been Worthen’s outside counsel for 50 years. And as Arkansas’s largest bank, Worthen had been the major depository of state money since Bill Clinton was a little boy.

Davis’s central premise was that Stephens, Inc., and the Stephens family had pocketed vast ill-gotten wealth through shady bond deals with the Clinton administration. As he put it, “The intimate connection between Rose, Stephens, Inc. and the Governor’s office may help explain how the Stephens family made a huge amount of money when its most visible enterprises were doing no such thing.”

Passing over the fact that the Stephens interests had bankrolled every GOP gubernatorial nominee (except the hated Sheffield Nelson) in recent Arkansas history, the notion that Clinton had made the family rich provoked helpless laughter in Little Rock. The value of Stephens, Inc., comprised just under seven percent of the Stephens family’s $1.7 billion net worth. Besides vast natural gas reserves in Arkansas and four western states, they owned huge soft coal reserves, banks, gas and electric utilities, newspapers, and scores of other concerns. During Clinton’s tenure, Stephens, Inc.’s underwriting fees on Arkansas bonds came to less than 1 percent of the firm’s total revenues.

But what really made L. J. Davis temporarily famous wasn’t the Wall Street Journal‘s endorsement of his sinister view of Arkansas politics, but its account of an alleged act of violence against him. In covering Clinton, lamented Journal editors the week Davis’s article appeared, the “respectable press… has shown little or no appetite for publishing anything about sex or violence,” a taboo they would no longer observe.

On the evening of February 13, the same editorial recounted, Davis “was returning to his room in Little Rock’s Legacy Motel about 6:30 after an interview. . . . The last thing he remembers is putting his key in the door, and the next thing he remembers is waking up face down on the floor, with his arm twisted under his body and a big lump on his head above his left ear. The room door was shut and locked. Nothing was missing except four ‘significant’ pages of his notebook that included a list of his sources in Little Rock…. Mr. Davis says his doctor found his injury inconsistent with a fall, and that he’d been ‘struck a massive blow above the left ear with a blunt object.’ ”

The Journal concluded that Arkansas was “a congenitally violent place, full of colorful characters with stories to tell, axes to grind, and secrets of their own to protect.” In this climate, the editors concluded, “the respectable press is spending too much time adjudicating what the reader has a right to know, and too little time with the old spirit of ‘stop the presses.’ ”

The near-martyrdom of Davis fit perfectly with the Foster “murder” and the Clinton Chronicles death list. Rush Limbaugh and his imitators on right-wing talk radio professed shock and horror. Rumors spread among the Washington press corps that the phones in Little Rock’s Capital Hotel, owned by the Stephens interests, were bugged, and that Bill Clinton employed thugs and gumshoes to shadow reporters in Arkansas.

Oddly, L. J. Davis himself soon discovered that the crucial four pages weren’t missing from his notebook after all, merely torn and wrinkled. Still, the Democrat-Gazette, alarmed that a colleague had been assaulted in downtown Little Rock, sent reporters out looking for the perpetrator. They didn’t take long to find a suspect.

According to Legacy Hotel records, the assailant appeared to be a half-dozen straight gin martinis. During the same four hours that Davis reported having spent facedown on his hotel room floor, he’d actually been seated upright on a barstool. Hotel officials showed a copy of his bar tab to Little Rock police, and the bartender distinctly remembered refusing Davis a seventh drink.

The writer denied drinking more than his usual ration of martinis, although he didn’t specify how many that was. “I might have been a little happy, but so what?” he told reporters. “I have never made any charge about that, and why am I going to call the cops if I don’t know what happened?”

FromThe Hunting of the President, by Joe Conason & Gene Lyons, Copyright © 2000 by Joe Conason and Gene Lyons. All rights reserved.

If you enjoyed this excerpt, purchase the full book here.

Want more updates on great books? Sign up for our email newsletter!

Trump Cabinet Nominee Withdraws Over (Sane) January 6 Comments