Reprinted with permission from Creators.

On May 14, 1973, two months after John McCain’s release from a North Vietnamese prison, U.S. News & World Report published his 43-page essay about what he had endured there.

His narrative of his 5 1/2 years as a prisoner of war — the torture, the starvation, the intermittent waves of doubt that he would survive — is unsparing and harrowing, and it’s void of hyperbole.

“The date was Oct. 26, 1967,” he begins. “I was on my 23rd mission, flying right over the heart of Hanoi in a dive at about 4,500 feet, when a Russian missile the size of a telephone pole came up — the sky was full of them — and blew the right wing off my Skyhawk dive bomber. It went into an inverted, almost straight-down spin. I pulled the ejection handle, and was knocked unconscious by the force of the ejection. … I didn’t realize it at the moment, but I had broken my right leg around the knee, my right arm in three places, and my left arm.”

His description of solitary confinement: “I was not allowed to see or talk to or communicate with any of my fellow prisoners. My room was fairly decent-sized — I’d say it was about 10 by 10. The door was solid. There were no windows. The only ventilation came from two small holes at the top in the ceiling, about 6 inches by 4 inches. The roof was tin and it got hot as hell in there. The room was kind of dim — night and day — but they always kept on a small light bulb, so they could observe me. I was in that place for two years.”

When he refused to be released before his fellow POWs, one of his captors told him, “Now, McCain, it will be very bad for you.”

He was tortured for the next year and a half. They broke his left arm again and cracked several of his ribs. He describes “the lowest point,” when he was on the brink of suicide and wrote a dictated confession. “I had learned what we all learned over there: Every man has his breaking point. I had reached mine.”

He was finally released on March 14, 1973, with 106 fellow U.S. flyers and one American civilian.

His essay ends with his future plans: “I had a lot of time to think over there, and came to the conclusion that one of the most important things in life — along with a man’s family — is to make some contribution to his country.”

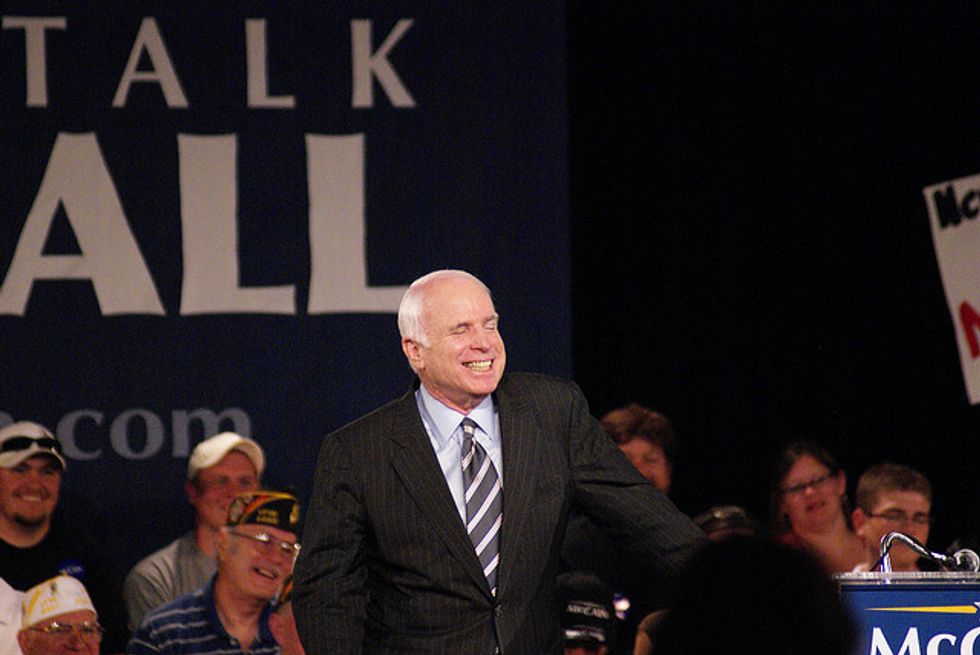

After all that, John McCain wanted to serve.

In response to my expressing respect for him and sympathy for his family, I’ve received numerous links to opinion pieces detailing his many flaws. I’ve never thought that paying tribute, in death, to the best parts of a person means we’re ignoring the worst. I seldom agreed with McCain politically, and I could rattle off missteps in his public life. But I am mindful of his private life during those years in that cell in Hanoi, and that will forever inform my view of him.

My home county of Ashtabula, in the northeastern corner of Ohio, lost 26 boys in Vietnam. Countless others served, and many returned as someone else. They were farm boys and working-class kids, and they were drafted. No college deferments, no influential fathers or friends of fathers to keep them out of harm’s way. They didn’t flee to Canada or even consider becoming conscientious objectors, because that’s not what you did where I grew up.

I understood at a young age that you don’t attack men whose only option was to do what their country told them to do. I judge no one who found a way to avoid going to Vietnam, as long as these people acknowledge the privilege of their deferments, as well as the sacrifices of those who weren’t so lucky.

Which brings me, ever so briefly, to Donald Trump. I will not rehash what he has done to disrespect McCain after his death. Most of us aspire to evolve as human beings, which requires us to discard those parts of us that diminish us. Some, however, just never learn how to take out the trash. That filth has a way of pooling around you.

Over the years, I occasionally crossed paths with McCain. Only once did I talk to him about his time as a POW, during a dinner before Pope Francis’ speech to Congress in September 2015. Five years earlier, I had traveled to North Vietnam to report on the enduring legacy of Agent Orange. McCain inquired at length about my conversations with veterans there.

I told him I had visited the Hanoi Hilton, which is now a museum, and had seen his flight suit displayed in a glass case. He smiled and shook his head.

“That wasn’t mine,” he said. “They made that up.”

That was it. No tales of suffering at the hands of his captors. No mention of his permanent injuries from their torture. Not a single sign of enduring resentment. He just shrugged at my look of surprise and smiled again.

“You learn to let things go,” he said.

That’s what I want to remember about John McCain.

Connie Schultz is a Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist and professional in residence at Kent State University’s school of journalism. She is the author of two books, including “…and His Lovely Wife,” which chronicled the successful race of her husband, Sherrod Brown, for the U.S. Senate. To find out more about Connie Schultz (con.schultz@yahoo.com) and read her past columns, please visit the Creators Syndicate webpage at www.creators.com.