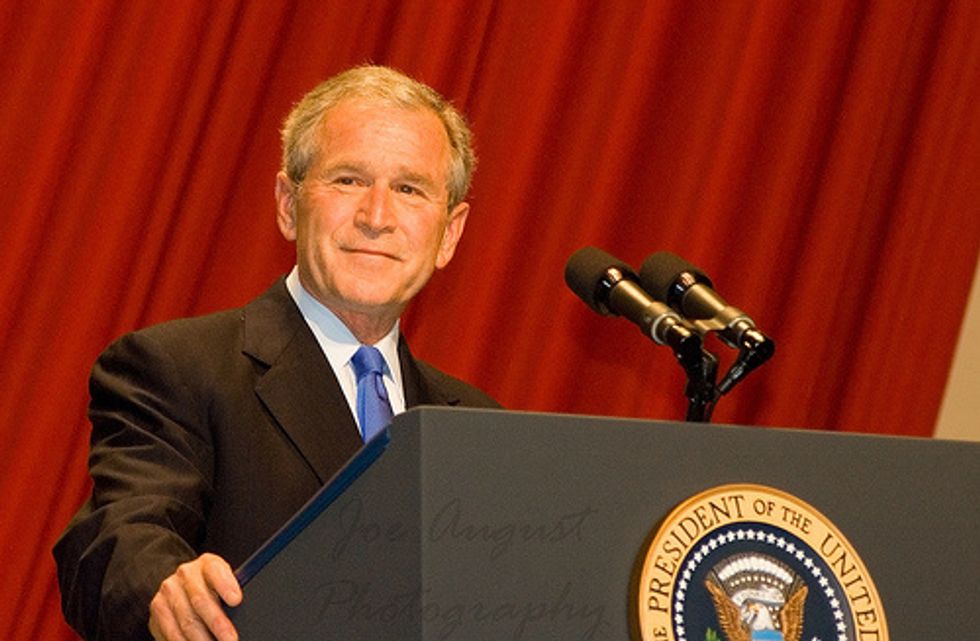

When George W. Bush made his first public appearance in many months to discuss economic policy in New York on Tuesday, his utterances may have revealed more than he intended. “I wish they weren’t called the ‘Bush tax cuts’,” he said of the decade-old rate reductions that bear his name. But does he really believe, as he seemed to suggest, that Americans want to let those cuts expire from a desire to spite him? Or is there a deeper Bush somewhere within who would prefer not to be associated with fiscal profligacy and ideological overreach?

Whatever his motives, Bush’s curious remark draws a sharp contrast with his predecessor Bill Clinton – who often speaks proudly of the tax increase that was so central to his first budget as president two decades ago. Clinton, who speaks publicly far more often than Bush, frequently notes that the 1993 tax increase was the first step toward balance and growth after a dozen years of Republican irresponsibility and stagnation.

It isn’t clear that Bush actually understands the indelible effects of his tax and spending policies. Someone should explain to him what is so painfully obvious when the numbers are added up: Not only should the tax cuts be named after him. So should the deficit and the debt.

The simple math is worth keeping in mind when Bush turns up to advocate maintaining the cuts he passed and legislating still more, which he claims wiill stimulate the private sector. “Much of the public debate is about our balance sheet…or entitlements,” he said , but the solution in his view is to focus on private sector growth. ”The pie grows, the debt relative to the pie shrinks and with fiscal discipline you can solve your deficits,” said Bush at a Manhattan conference sponsored by his George W. Bush Presidential Center on “Tax Policies For 4% Growth.” Bush Center fouding director James Glassman was present to repeat all the usual Republican bromides about incentivizing growth by cutting taxes on the wealthy, preferably to zero.

But as Clinton points out in Back To Work, the book he published last fall, it was his tax increases on the upper brackets (along with spending cuts) that propelled the country toward fiscal balance and a vanishing debt before Bush assumed office in 2001. “When I was president,” he wrote, “we passed the 1993 budget to reduce the deficit by $500 billion, roughly half from spending cuts, half from tax increases, with only Democratic votes. The bill produced a much greater reduction in the annual deficit than experts predicting, eliminating roughly 90 percent of it even before the Balanced Budget bill was enacted [emphasis in text], because it led to lower interest rates, more investment, and higher growth.” (See pages 35-43, with charts.)

The economic narrative of the Republican presidential campaign will blame increased deficits and debt on President Obama — and argue that cutting federal budgets while reducing taxes on the wealthy will somehow restore growth. Certainly that is what Bush tried to suggest in New York when he spoke so wistfully of his endangered tax cuts. But the math undercuts him. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Bush’s tax cuts and war spending will account for nearly half of the $20 trillion in debt that will be accumulated by 2019. (That doesn’t include his misconceived and costly Medicare prescription drug benefit.) The Obama stimulus and financial bailouts, including the auto revival, will be responsible for less than $2 trillion of the total debt by then, or less than 10 percent.

With due respect to the former president, public revulsion over his failed policies long ago transcended him. Those Bush tax cuts,by any other name, would smell no sweeter.