In the aftermath of today’s attack on the Bacha Khan University in Charsadda, Pakistan, it is worth understanding the ideals of the man for whom the university was named. His outlook continues to serve as a model for communal coexistence that harkens back to the pluralistic society that existed in South Asia centuries before British divide-and-rule policies set Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs against each other.

Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, known commonly as Bacha Khan, was a Pashtun activist who advocated for a united, secular India alongside Mohandas K. Gandhi’s Indian National Congress, back when India and Pakistan were under British rule as a single colony known as the British Raj. The two leaders shared a deep friendship that continued until 1947, and Bacha Khan often provided critical support to the Congress throughout the last decades of colonial rule in India. In 1929, he had set up the Red Shirt movement (Khudai Khitmatgar), a nonviolent political organization that provided the Congress Party with crucial support in India’s majority-Muslim western provinces.

Khan articulated his nonviolent worldview by invoking prophetic tradition, telling his followers, “The Holy Prophet Mohammed came into this world and taught us ‘That man is a Muslim who never hurts anyone by word or deed, but who works for the benefit and happiness of God’s creatures.’ Belief in God is to love one’s fellow men.” Among Khan’s central tenets was serving all of humanity, without discriminating against religion or race, in the name of God.

That commitment to peace and tolerance is a crucial point of divergence between Khan’s Red Shirts and today’s Taliban attackers. While Khan served the people regardless of their faith or past actions, groups like the Pakistani Taliban, which killed 132 schoolchildren at a military school in Peshawar last year, claim to be doing so for themselves. In its public statements, the Taliban justified the attacks: “We selected the army’s school for the attack because the government is targeting our families and females,” said Taliban spokesman Muhammad Umar Khorasani. “We want them to feel the pain.”

Khan probably wanted the British colonial authorities to also feel pain. They had colonized his country, put down numerous insurrections with unrivaled brutality, and killed hundreds of his supporters in an attempt to provoke them. Beyond that were the millions who died in the process of colonizing India, a death toll far higher than whatever the Pakistani Taliban has suffered. But Khan’s supporters never attacked the British soldiers suppressing their cause, let alone innocent civilians in public spaces like universities, squares or markets. And his efforts paid off.

Following the 1930 massacre of Red Shirts in Peshawar, not far from the scene of today’s attack, massive changes in Indian colonial politics took place. The Red Shirts were thrust to the national political scene as a result of their adherence to nonviolence, even at the cost of the deaths of hundreds of their own. In fact, despite the large membership of the Red Shirts, there has been no evidence that anyone was killed by a Red Shirt.

Even King Edward VI, British monarch at the time, couldn’t ignore how bad British troops looked for shooting nonviolent protesters, although it was not the first or last time such atrocities would occur in British India. The king set up a legal investigation into the incident, which he then tried to influence, which resulted in a 200-page report criticizing British actions and a resolution taking the side of the local population.

Following the creation of Pakistan, a division that Bacha Khan personally opposed (he told Gandhi upon hearing that the Congress Party accepted the partition that “you have thrown us to the wolves”), he pushed for the creation of a Pashtun-dominant region in Pakistan. More than once he was arrest on false charges of plotting to assassinate Mohammed Ali Jinnah, the ailing founder of Pakistan, and for opposing the One Unit policy in the 1950s, a plan to consolidate Pakistan’s four provinces into a single unit to counterbalance the political power of Bangladesh back when it was part of Pakistan.

When Bacha Khan died on January 20, 1988, his body was transported to Jalalabad, Afghanistan. Pakistan’s western neighbor, still in the midst of fighting the Soviet invasion, declared a ceasefire while mourners traveled to his burial site. The Indian government declared five days of national mourning to mark his death.

Perhaps today’s attack was deliberately perpetrated on the anniversary of his death. But even a bloody assault on an institution named after him won’t snuff out Khan’s vision of coexistence and cooperation. The humanism he embodied and the universal respect he earned from the religious and ethnic groups of the region made him an enduring hero to all.

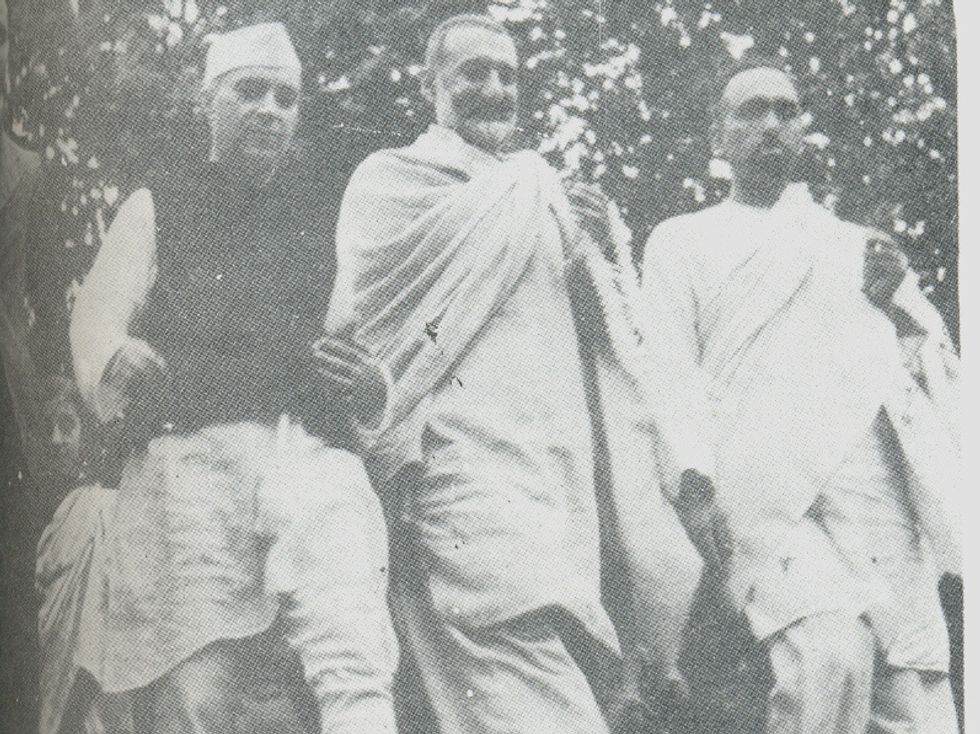

Photo: From left to right: Future Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Bacha Khan and Sheikh Abdullah, a Kashmiri politician, walk together in Srinagar in the 1940s.