Republicans are likely to leave the Affordable Care Act in place, but only because their backers in the insurance industry fear the alternative.

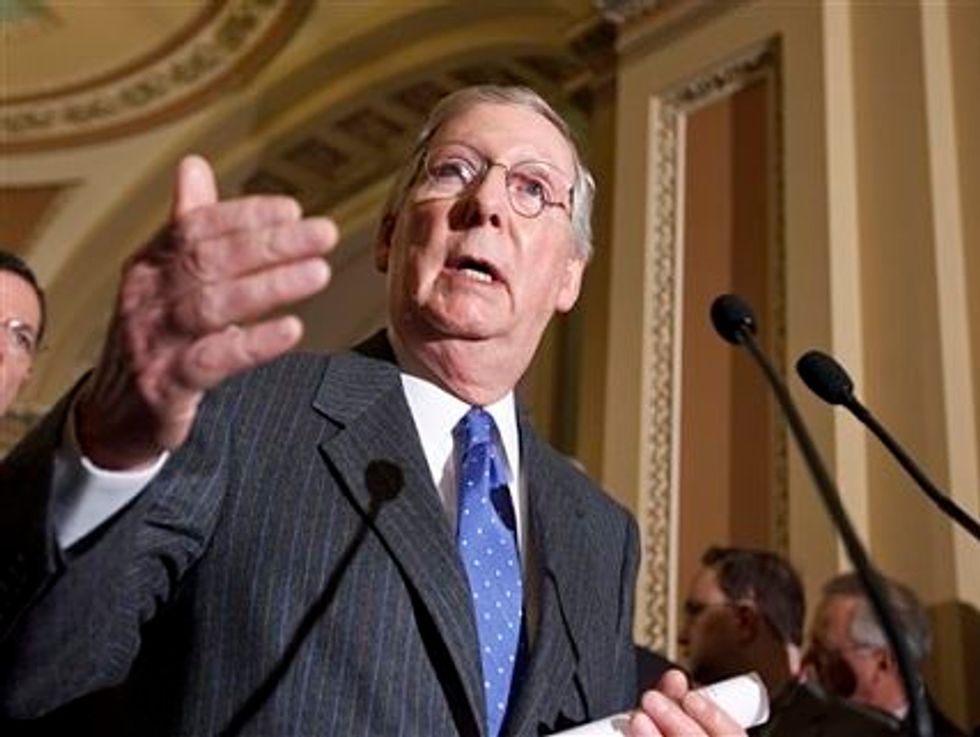

“If I’m the leader of the majority next year, I commit to the American people that the repeal of Obamacare will be job one.”

– Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell, on Fox News Sunday

“If you thought it was a good idea for the federal government to go in this direction, I’d say the odds are still on your side. Because it’s a lot harder to undo something than it is to stop it in the first place.”

– Mitch McConnell, in Elizabethtown, KY, on Monday

With the Supreme Court ruling upholding the core of the Affordable Care Act, Republicans at every level have renewed their promise to repeal it. It is Mitt Romney’s “Day One” task. Because Chief Justice John Roberts upheld the individual mandate under the taxing power in the Constitution, conservatives such as economist Keith Hennessy and Virginia Attorney General Ken Cucinelli argue, the penalties for non-compliance are now a “tax,” and the mandate can be repealed under the federal budget reconciliation process, which can’t be filibustered in the Senate. That is, just 50 senators, along with a Republican vice president to break the tie, can repeal the mandate.

This is true – though the Court’s decision has nothing to do with it. Anything that has a significant impact on federal revenues or spending, such as fees, interest on student loans, or mining licenses, can be changed using the budget reconcilation process. The mandate, and some other provisions of the Affordable Care Act, can certainly be stripped out by a Republican majority. Other provisions that don’t affect the budget, such as some of the requirements placed on insurance companies to cover preexisting conditions and keep young adults on their parents’ plans, probably can’t be, because their effect on federal finances is minimal.

So if Romney wins the presidency and Republicans capture the Senate (as seems likely, if Romney wins), at the very least, we can expect them to repeal the individual mandate, right? It’s the least popular element of the law, and not too difficult to sever from the rest. As Paul Starr of Princeton and The American Prospect has argued for years, a mandate with minimal enforcement mechanisms might be worse than no mandate at all.

Whether they do that or not will be an interesting case study in the role of money in politics. Health insurance companies and HMOs, after all, are mainstays of the Republican money machine. Aetna, the health insurer that spends the most on lobbying, recently bolstered its Republican bona fides by being the first public corporation to disclose recent contributions to Republican dark-money committees, the American Action Network and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s political arm. Aetna’s former CEO, Ronald Williams, even went so far as to renounce the company’s long-standing support for the mandate, predicting it would fall at the Supreme Court.

But for health insurers like Aetna, stripping out the mandate alone would be the worst possible outcome. It would mean that they would still have to take all applicants, and couldn’t reject or charge more to people with preexisting conditions. And they wouldn’t have the profits from younger, healthier customers. Ideally, companies like Aetna would like to have the mandate without any of the other reforms, but that’s a political non-starter, since individuals would be mandated to buy something that the insurers would refuse to sell them. Failing that, the insurers could live with the Affordable Care Act, or the pre-ACA status quo. But what they can’t live with is the insurance reforms alone, without a mandate. (As a spokesperson for America’s Health Insurance Plans told Reuters, “There has always been broad agreement that the insurance market reforms… cannot work without universal coverage.”)

And you can be pretty sure that they won’t have to. By deepening their alliance with the Republican Party, Aetna and other insurers have made sure they would be at the table, whether the Court overturned the mandate (in which case the insurers’ goal would be to undo the rest of the law) or upheld it.

Some Republicans, including Romney, promise to repeal the whole law and “replace” it with something better, often suggesting that the replacement would include the popular provisions on preexisting conditions. That, too, is a non-starter with the party’s cash constituents. And other Republican proposals, such as to allow insurance companies to sell across state lines – that is, evade state regulations – aren’t ready for prime time. Republicans never offered an alternative during the health care debate and they don’t have one now.

Thus you have McConnell’s careful lowering of expectations on Monday: “It’s a lot harder to undo something than it is to stop it.” The Republicans will talk about repealing “Obamacare” for as long as it succeeds in firing up their base. But it’s all cheap talk; they won’t do a thing.

And so, the Affordable Care Act is secure. Unfortunately, that has less to do with public opinion or the Constitution than the simple power of money in politics.

Mark Schmitt is a Senior Fellow at the Roosevelt Institute.

Cross-Posted From The Roosevelt Institute’s Next New Deal Blog

The Roosevelt Institute is a non-profit organization devoted to carrying forward the legacy and values of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt.