Oct. 20 (Bloomberg View) — We are in the business of making mistakes. The only difference between the winners and the losers is that the winners make small mistakes, while the losers make big mistakes. –Ned Davis

I began my career in finance on a trading desk. You learn some things very early on in that sort of situation. One of the most important things is that while it’s OK to be wrong, it can be fatal to stay wrong.

Unfortunately, that standard doesn’t apply to people whose work isn’t evaluated on a daily and objective basis via their profit and loss results. In many fields, such as politics and policy making, there are lots of shades of gray when it comes to being right or wrong.

And quite bluntly, that is a shame. As a society and a nation, we would all be better off if the people who are consistently wrong paid some sort of price for those errors. Unfortunately, that doesn’t happen enough these days.

Some bad policy decisions will lead to the occasional elected official being turned out of office. That — unfortunately — is the exception, not the rule. I doubt history will rank George W. Bush and Barack Obama among our great presidents, but both were re-elected despite being unpopular. Between gerrymandered congressional districts and apathetic voters, even the most incompetent elected official has almost lifetime tenure.

What underlies all of this nonrecourse bad policy? It is much more than corporate lobbying and partisan politics. The worst of today’s political malfeasance is being driven by failed ideologies. Zombie ideas that refuse to die have become enshrined in our collective intellectual legacy. The people behind these have been insulated from the economic costs they impose.

Blame the billionaires.

They are ones who fund the think tanks. These think tanks in turn consider it their jobs to promote the ideology of their benefactors, regardless of its intrinsic value or demonstrable worth.

This theme keeps coming up again and again. About a year ago, I reminded people of a letter written to the Federal Reserve in 2010 warning that the central bank’s asset purchases risk “currency debasement and inflation,” none of which occurred. That meme propagated, leading to a series of articles across the blogosphere and mainstream media. Most recently, Bloomberg News tracked down the signatories to that letter, to see if they were willing to acknowledge that they were wrong. Not a one was willing to admit error. Perhaps the lack of contrition is best summed up by this New York magazine headline, “If Being Wrong About the Economy Is Wrong, I Don’t Wanna Be Right.”

These errors have a persistence that shouldn’t continue once the invalidity of the underlying belief system is demonstrated. But they continue on, as zombie ideas that refuse to die. Consider the following short list of disproven ideas, all based on concepts that originated from or were widely dispersed by think tanks or their benefactors:

• Homo economicus (profit maximizing economic actors)

• Austerity as a virtuous policy during recessions

• The efficient-market hypothesis

• Tax cuts pay for themselves (supply-side economics)

• Self-regulating markets

• Shareholder value

• Rational Investors

Some of the bad ideas that come out of the think-tank world eventually acknowledge that they are untrue by slowly morphing into a new shape.

Let’s consider a few of these bad ideas. The pushback against anthropogenic climate change, or manmade global warming, has gone through a three-step process: First, there were the simple denials: It doesn’t exist, temperatures aren’t rising, etc. The next step was: OK, climate change exists, but it’s a natural phenomenon, not manmade and is caused by sunspots or the end of the Ice Age from 10,000 years ago. The last phase is simply to say, regardless of the cause, it costs too much to do anything about anyway. Grist provides a thorough debunking of denialism in all its forms; if you want a more scholarly approach, try The Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society.

We saw a similar progression during the financial crisis, including many attempts to negate the role radical deregulation of financial markets had as an underlying cause of the crisis. American Enterprise Institute’s Peter Wallison and Edward Pinto were the leading proponents of the anything-but-deregulation causation. First, they blamed the Community Reinvestment Act — the anti-redlining legislation that had nothing to do with subprime lending. Next, it was the Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Federal Housing Administration. When that didn’t hold up, they blamed Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. When most of the subprime loans that went bust were shown to be from private lenders that didn’t follow Fannie or Freddie guidelines, they quietly changed the subject.

As we have noted before, there simply is no penalty for pundits who keep getting it wrong.

As investors, we suffer greatly when we make an error that we fail to reverse. That was what Bridgewater Associates founder Ray Dalio was referring to when he said “More than anything else, what differentiates people who live up to their potential from those who don’t is a willingness to look at themselves and others objectively.” But it’s as true about our society as it is our P&L. The sooner we recognize that, the better off the country will be.

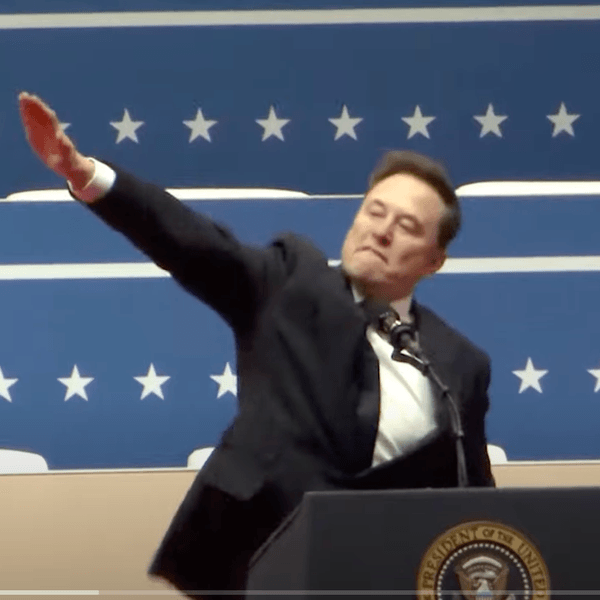

AFP Photo/Timothy A. Clary